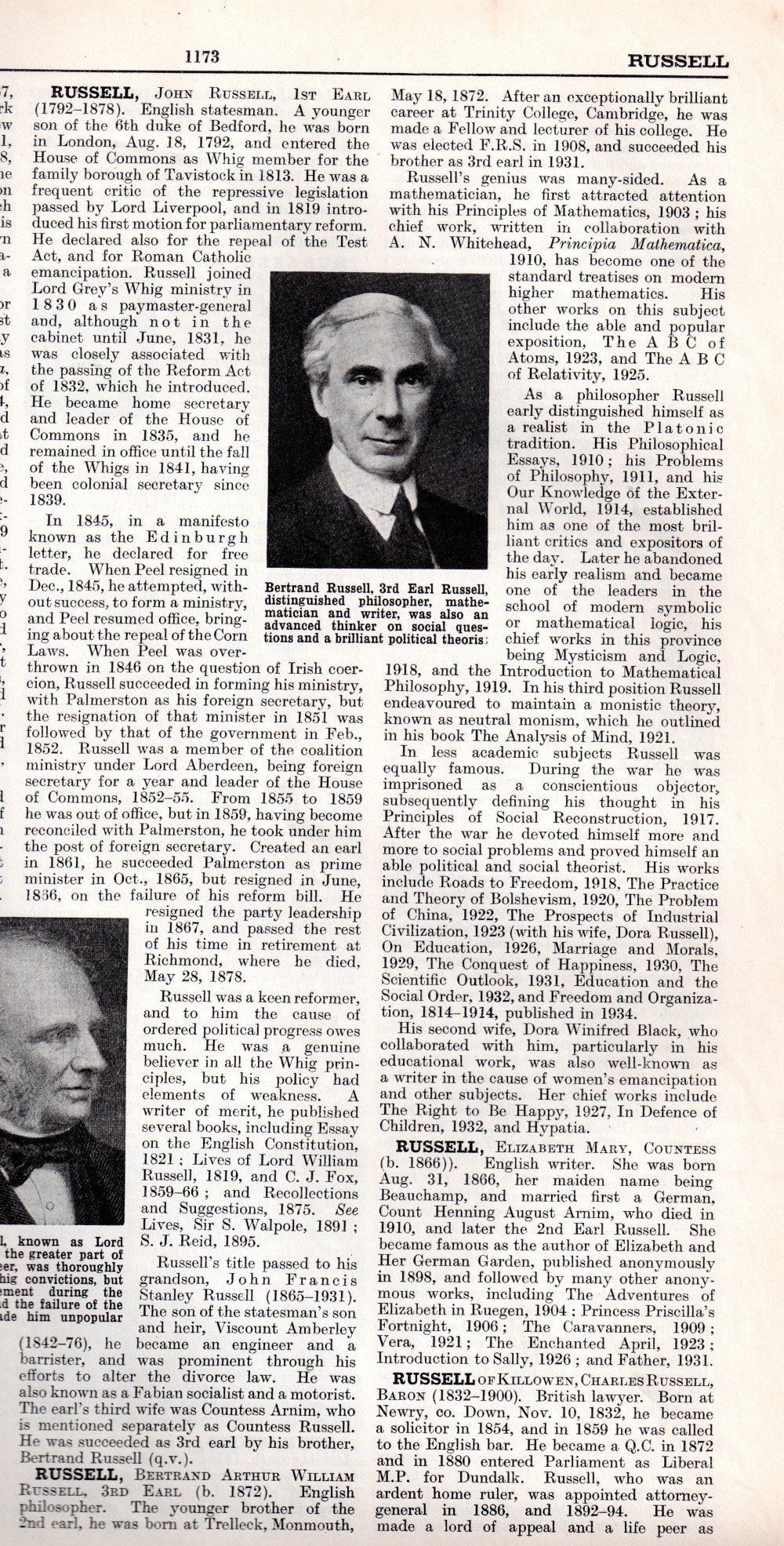

Bertrand Russell 1872-1970.

Some book reviews by Raeto Collin West, 'Rerevisionist'.

BR's publication date order. These reviews have been separated from big-lies.org/reviews (that file is too large).

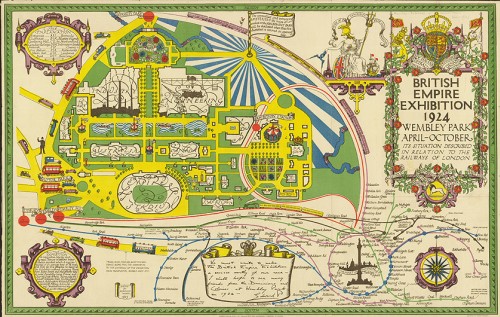

v. 19 August 2024It's saddening to read his autobiography: He is unblithely unaware of the huge evils of Victorian times, such as the viciousness against India and China, and the US Civil War horrors. He shows little grasp of the reach of aristocratic families in Europe and its provinces, such as Russia and the Americas. His work on nuclear weapons is now clearly entangled with Jewish lies. His work on Vietnam (during which he was corralled by Jews, though to what extent is not known by me)—as usual, Jewish concealment was as effective as they could make it. Possibly he was used as a ridiculable front in the worldwide dislike of American atrocities.

My revisionist review of Russell's life and work: Bertrand Russell: Dupe of Jews which is not in this page, but included in the 'nuke-lies' part of my site.

1952 film of Russell at home (black and white; 30 minutes; opens in a new tab). Disappointingly, shows Russell aged almost 80, in a staged conversation at home in (I think) Richmond—film being expensive and needing lighting and several cameras—in which it's clear Russell knew nothing of Jewish ambitions, the 'French Revolution', the slow perversions of thought against Germany in Britain and Britain in Germany, the 1913 Federal Reserve and 1914, Jewish mass murder under 'Socialism', Hitler, US ignorance, 'nuclear weapons' and other Jewish frauds, and many other topics. Russell regards 'Asia' as requiring to shoulder its responsibilities. He had no idea that Jews were and are 'supremacists'. He lived before the vast population expansions of black Africans, and the practical implementation of Coudenhove-Kalergi's plan, of which he was aware.

It doesn't say much for Victorian historians that they left huge questions over the 'French Revolution', as Russell demonstrates with his comment (for example in Dear Bertrand Russell), on inevitable Bonapartism. He was as bad on the USA Civil War, and Franco-Prussian War, and of course Jewish assassinations by anarchists and others. Sinn Fein is another.

Russell shows his unawareness of Jewish maleficence in his attitude the Jewish view of 'truth'. In his 1918 book Roads to Freedom, essentially a propaganda piece for Jewish ideas on harming the white world to make leading Jews feel happier, he wrote:–

There's more in the same sense, which might have been written by a Jew in 'Tikkun Olam' mode combining self-praise with discussion of how best to use the worthless 'goyim'.

And here he is published in 1973, in interview with Ralph Miliband, a 'Belgian' Jew.

RUSSELL: Oh yes, I’ve never seen any reason to change it. I find it very odd, very odd, that when people talk about religion they never enquire whether it is true or not: they only make out that it’s useful. But I don’t think a thing which is false can be useful, because it leads you astray.

'It' is his opinion of religion. He doesn't notice that it can be useful in leading other people astray. Something applied by Jews for thousands of years.

Just another philosopher: 1976 film of Isaiah Berlin interviewed, entitled Why Philosophy Matters. Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997), a 'Jew' of course, was touted as a historian of ideas. The interview shows him puzzling over the meanings of words—it looks very much as though he was uneasy with the English language, reasonably enough for someone who considered himself a Jew from Latvia. We also have an anecdote about the Second World War, in which of course he takes the Jewish view as automatically as possible, though no doubt there's some hesitation. He wrote a long review of Russell's History of Western Philosophy.

Copyright issues: Only two remarks I'm aware of refer to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, and The Managerial Revolution by James Burnham. Russell thought his ideas in Religion and Science were a copied by Huxley, and that Burnham had taken up the thesis of Power and popularised it. I'm personally uneasy about these claims; for one thing, Religion and Science was itself standard matter, generally quoting received anti-Church views. And Burnham seemed to present standard American views, probably of course Jewish.

More ordinary issues include copyright in his own works—see Anton Felton, below. And a brief humorous comment to a woman who thanked God for his Autobiography, suggesting that He might have infringed Russell's copyright.

German Social Democracy 1896 (lectures. Date corrected!)

Why Men Fight [in US] = Principles of Social Reconstruction 1916, written 1915

Political Ideals 1917 [US only]; 1963 [UK]

Roads to Freedom 1918. Long.

Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy 1919

Practice and Theory of Bolshevism 1920

The Analysis of Mind 1921

The ABC of Atoms 1923

Prospects of Industrial Civilization 1923

The ABC of Relativity 1925

On Education 1926. My plea for Jew-aware education

Sceptical Essays 1928

Education and the Social Order 1932

Freedom and Organization 1814-1914 1934.

In Praise of Idleness (1935)

Religion and Science 1935 (Published by Home University Library)

Which Way to Peace? 1936 First ever Internet upload! Complete text. 30 June 2017. NEW!!

Power: A New Social Analysis 1938

Let the People Think 1941 (Review Aug 2017)

History of Western Philosophy 1945

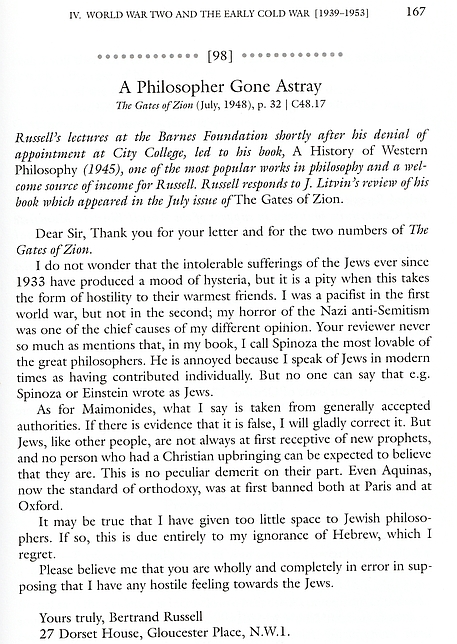

Extract from History of Western Philosophy: Russell on Jews 1945

The Impact of Science on Society essay collection 1952

'Why I am not a Christian' and Other Essays essay collection

Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare 1959

My Philosophical Development 1959

Fact and Fiction 1961

[Herbert Gottschalk, eine Biographie 1962]

War Crimes in Vietnam My review of this essay collection 1967

Download entire book here in pdf format. c 50MB

Autobiography (3 vols, 1967, 1968, 1969)

Against the Crime of Silence: Russell International War Crimes Tribunal 1968. My short review

Rupert Crawshay-Williams: Russell Remembered 1970

Allen Lane book Prevent the Crime of Silence in full 1971 with notes on Penguin Books propaganda and Jew-aware interpretation of Vietnam War. Some, but not much, by Russell who was in his mid-90s at the time

The Collected Stories of Bertrand Russell (1972)

Barry Feinberg: Bertrand Russell's America, 1945-1970 v1 1973; v2 1983?

Ronald W Clark: The Life of Bertrand Russell 1975

Katherine Tait: My Father, Bertrand Russell 1975

Caroline Moorehead: Bertrand Russell: A Life 1992 | Rerevised long update about 10 years later. Jews telling lies and covering up. Includes Schoenman.

Yours faithfully, Bertrand Russell 2002 | Edited by Ray Perkins Jr

German Social Democracy

1896 lectures, delivered at the LSE, which then was very new while pretending in Jewish style to be old and established. (About twenty years later, Principles of Social Reconstruction was delivered as lectures. Russell seems to have needed claqueurs to help him out.)

Russell's first book; he visited Germany with Alys for 'research', but, unsurprisingly, found only Jewish publications, which outnumbered non-Jewish by a vast margin.

Marxism and Politics by Ralph Miliband, published in 1997.

Note 6 (in the top right) refers to H. Gruber, International Communism in the Era of Lenin, published in New York, 1972.

It's unlikely Russell would even have noticed anything published against Jews.

Review of Bertrand Russell Autobiography. Three volumes first published by Allen & Unwin 1967, 1968, 1969

Review of Bertrand Russell Autobiography. Three volumes first published by Allen & Unwin 1967, 1968, 1969 Reasonably Honest Autobiography, Largely Greeted with Enthusiasm, by a British Aristocrat Torn Between Philosophy, Science, and Nascent Social Sciences. 11 March 2016.

Reasonably Honest Autobiography, Largely Greeted with Enthusiasm, by a British Aristocrat Torn Between Philosophy, Science, and Nascent Social Sciences. 11 March 2016.

Volume I 1872-1914

Russell was born in 1872; old enough not to have been called up in the 'Great War'. Volume 1 of his Autobiography (with the green jacket design spine, and a black-and-white cover photo by Lotte Meitner-Graf, a copy of which appears in Chomsky's study, and in a 1970s film including Malcolm McDowell) was published by Allen & Unwin, his lifelong publisher. Volume I is 1872-1914; Volume II 1914-1944; Volume III 1944-1967 (from memory) with a 'tailpiece' of 1969. These divisions clearly correspond to milestones in Russell's mental life: the outbreak of the 'Great War', and the supposed invention of nuclear weapons.

There were astounding changes in Russell's lifetime: automobiles and aeroplanes and skyscrapers hardly existed until he was about 40 years old. Underground and tube railways first came to London somewhat earlier. Telephones were rare and valuable. Oil-based plastic polymers were hardly known before 1945. Machine guns and dynamite pre-dated 1900. Their later developments were in time to be misreported by radio, and then television. Russell recognised the power of TV: he thought most people would believe any lie promoted by television.

When this autobiography appeared, flattering blurbs suggested it was remarkably honest. I don't think this is quite true. Russell had many 'relatives'—I don't know the phrase Russell would have used. Not 'extended family'. Probably 'my people'. But there's nothing like a family tree. I think this expands the impression of loneliness in a misleading way.

Russell's longevity reflects on his cultural background. He was not of a temperament to be attracted to Greek and Roman classics; these had their day, but were outdated by Victorian progress. He was hopelessly impractical, not having any empirical scientific skill, though he recognised the importance of science. Such books as Lewis Carroll's and Edward Lear's, Tristram Shandy and The Trumpet Major and War and Peace (later, in English) and the Cambridge Modern History were part of his upbringing and early maturity. Alys Pearsall Smith (his first wife, an American New England Quaker) and Russell ploughed through standard histories together, as Darwin and his wife did. I don't think Russell ever applied scepticism to history: for example, about Nero, or Cromwell, or the Protestant view of the Reformation, or the French Revolution. Before this, his early years in his grandfather's gift-of-Victoria house in Richmond Park were partly spent looking through Prime Minister Russell's library, though L'Art de Verifier des Dates (the only 'art' involved was looking them up) is the only book (I think) he specifically locates there.

All Russell's early years were spent, more or less in isolation, in Richmond Park, with his elder brother Frank, his servants, and elderly relatives, notably an ancient puritanical Scottish grandmother—it's not clear to me which of his parents was her child. As in many European countries, aristocrats carried with them a considerable penumbra of hangers-on. Possibly there was a painful waste of talent: they might have observed the world more than they did. But equally possibly there was not; it's agonising to reflect on the missed opportunities.

Pembroke Lodge still exists, in a state of conversion into tea room with car park, and a huge outdoor poem carved into wood: City of Dreadful Night. Poor Russell is almost elided away by now. He loved the landscape and nature, which he thought of as wild, and described in old age with great vigour.

When Russell was young, Joseph Conrad did not of course exist as part of a more-or-less official literary canon. Shelley was there—Russell read Epipsychidion aloud to Alys in between kissing sessions. Byron furnished materials for Russell on 'Byronic unhappiness'. The really immense historical upheaval at that time was the French Revolution and Napoleon, and the preceding philosophical groundwork, Voltaire, Blake, Swedenborg and so on, but especially Rousseau, who retained an aura of irresponsibly-'romantic' evil in Russell's mind. The simple outline of this historical set of events (including slogans, the terror, and military conquests) adapted itself well to the so-called 'Russian Revolution' of volume 2 of Russell's Autobiography. Russell never had any doubt about this scheme, and for example always called the Jewish-run 'Union of Soviet Socialist Republics' Russia, as though it was simply another nation-state made up of one well-defined nationality.

Russell regarded himself as a triple philosopher-mathematician-social scientist. His philosophical life started largely with his attack on Christianity, in his exercise book labelled 'Greek Exercises'. It's similar to other rationalistic attacks of the time, concentrating fire on falsehood and absurdity. Russell was too young or naive to understand that much of established religion is an income-generating scheme, though he must have been aware of the history of the Reformation as presented in 19th-century England. Anyway, at the end of this process Russell recalls feeling relieved that it was all over. When he finally went 'up' to Cambridge, he says he met only one person who had heard of Draper's History of the Conflict between Religion and Science. Russell claims to have been led into mathematics by his brother's explaining some of mysteries of geometry to him, from Euclid, including the problem of parallel straight lines not meeting. Aged about 18, he was ready for Cambridge, full of promise—the famous Jowett came to visit what there was of his family. (Both his parents died when he was young—too young to remember them). Russell's social science interests started in Volume II; before that, he worked at his Principia Mathematica. He claims to have discovered much of the work of Cantor independently. My own belief is that Cantor and (later) Einstein are flawed. I suspect Russell was well aware of fame and publicity and renown; most of his beliefs were in accordance with ideas currently promoted at the time. One of his 1930s essays, on Tom Paine and Washington and the early views of democracy, Russell states that 'Some worldly wisdom is required even to secure praise for the lack of it.' In Volume I this hardly mattered; Russell's views were not very controversial. But, at least in my view, Russell always had some intellectual timidity: he never dared criticise Freud, for example, in any forthright way.

Russell at Cambridge found Cambridge University life exactly suited to his tastes and abilities. He was sought out by intellectual clubs, was able to talk for the first time in his life, found the buildings beautiful, met Whitehead, and generally expanded. He bought and smoked Fribourg & Treyer's 'Golden Mixture'. He took very long walks. He rode his bike. He became less shy. He liked the ambience of completely free discussion, and never noticed it was much less free than he'd imagined. He made fun of people who tried to popularise. A note that strikes me as discordant is his dislike of the 'Dons'. He wrote prose with purple patches. As with almost all biographies, Russell writes very little on what he actually learned at Cambridge. He gives no summary or account of the influence of mathematical structures on his thinking. Very likely 'propositional functions' are one such thing, but he doesn't explicitly say so. He liked philosophy 'and the curious ways of conceiving the world that the great philosophers offer to the imagination.' His first philosophical ventures led him, following others, to criticisms of Hegel and German Idealism, though not of the assumptions and mind-sets that led to its being favoured.

Russell married (partly because he wanted children) and moved to a newly-built house. He was—I did some comparative calculations—the equivalent of a millionaire now, through inheritance. He was in a position to turn down work he found distasteful: for a short time in 1898 he tried diplomatic work in Paris, but disliked working on a dispute as to whether lobsters legally counted as fish. (Plus ça change ..: the EU had a dispute as to whether carrots count as fruit). It's not quite true to say that Russell was fully absorbed in philosophy and mathematics: his wife Alys spoke on votes for women and similar issues. I found a short essay by her in Nineteenth Century Opinion, taken from The Nineteenth Century of 1877-1901, in a 1951 paperback edited by Michael Goodwin (if you must know) in which she expressed the desire of single wealthy women for work—with the usual implicit restrictions. At the end of his chapter Principia Mathematica Russell wrote 'Few things are more surprising than the rapid and complete victory of this cause women's suffrage] throughout the civilised world.' Russell was impressed (unfavourably) by Philadelphia politics—as a long letter to Graham Wallas in 1896 on 'bossism' and voting fraud shows. (This letter is instructive: Russell provides examples of bosses' voting frauds, purchases of votes, paid fake demonstrators, as he somewhere in his writings comments on the skilled management of bankrupt US railways. He could never, at any time in his life, bring himself to analyse the costs of party politics and the economics of corruption. As he puts it: Americans are unspeakably lazy about everything but their business [and] invent a pessimism, and say things can't be improved). Russell and Alys went to Germany to study 'social democracy' there; the outcome was his very first book German Social Democracy (1896). This set a style for all Russell's social science books: he simply had no idea about Jews, which of course was a standard head-in-the-sand attitude in polite Britain. Probably he simply assumed the vast number of Jewish publications in Germany, and the tiny number of those discussing Jewish influence, must have been a plain reflection of merit. (If you're looking for a full-on criticism of Russell, see Bertrand Russell, dupe of racist Jews.)

Russell's following three books were An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry (1897), A Critical Exposition of the Philosophy of Leibniz (1900), and The Principles of Mathematics (1903). However, Russell doesn't write much about his books, which he often implied came from unconscious thought, as for example in his account of sitting in the parlour of the Beetle and Wedge at Moulsford, wondering what to say about 'our knowledge of the external world'.

One of the attractive characteristics of Russell's Autobiography is its peppering with famous names: G E Moore, J M Keynes, D H Lawrence, G B Shaw, Eddington, Einstein, H G Wells, Malinowski, Sidney and Beatrice 'Webb', as a tiny sample—though arguably some names are chosen for notoriety rather than firm reputation. Russell worked in Cambridge, London—at the time one of the world's largest cities— and his Hindhead house. And he had a large set of women companions, but this fact only emerged later, and is only very slightly present in his Autobiography. In this way, he might have proceeded from the 1890s to the twentieth century and onward, for the rest of his life as a respected academic, reading The Times and hefty Victorian books, with no inkling that other outlooks and forces were designing and plotting.

Woven into his narrative are relatives—often enough, surprising, because of the inevitable limitations of the first-and-surname principle. General Pitt-Rivers was his uncle. Lord Portal, responsible for bomber command (in Volume III) and perhaps therefore the Second World War, was Russell's cousin. The Duke of Bedford was 'head of my family'. And of course Russell had personal friends. Russell's chapters each end with a collection of letters. In Volume I, the final five chapters have far more letters than text, beginning with his life in Paris and dalliance with a diplomatic carrier. And Volume II has far more of his letters than text, many being his own, suggesting his early life had disproportionately the most emotional meaning for him, and that Russia, China, and America between them managed to exhaust him.

Volume II 1914-1944

Volume II 1914-1944Just a few comments on Russell's attitudes at the time. A run-in with a family doctor caused other family members to tell Russell he ought not to have children, because of the taint of insanity of a relative of Russell's. Russell said people at the time tended to believe overmuch in heredity. Since then, population movements have become so much easier that people if anything are at the opposite extreme, denying all role for genetics—this of course is the official Jewish view since 1945. The point really is that if people are to be ignored as sub- or non-human, as per Jewish orthodoxy, it doesn't matter if there are differences. Similarly with Russell: if you're a secure aristocrat, what do other people matter? Russell assumes all human populations are similar: his book on Power doesn't differentiate in any way between populations, though there are token references in his books on education. This must have had a lot of muting effect on his knowledge of the 'masses', and of Jews vs Russians. Inaccessible populations of southern Africa had been described for 50 or 60 years, but Russell failed to note systematic differences.

Russell was aware of, and discussed in his books, genetics and Darwin. He seems to have veered away from such awareness: a letter in Volume III says all Germans would have been 'sired by Hitler', for example. In a way it's odd, because he himself felt some need for intellectual accomplishment; and yet he was forbidden from reading books in his grandfather's library, and discouraged from rationalist critiques of Christianity.

Russell disliked 'capitalism', but seems to have taken the word and its connotations straight from Marx. Although he was aware of finances, and the power of panics and crashes and so on, his use of 'capitalism' was just like that of all the other 'economists' of the time trying, or pretending, to be critical. Quite apart from money, as far as I recall there is nothing in Russell on economic goods: Can there be too much? Should inventions made in A be allowed into B? Is there some law making some level of 'productivity' ideal? Is there an optimum population? Despite Russell's attempts, I don't think he discovered anything, though some people credit him with 'effective demand' and 'spending out of depression'.

I don't mean newspaper-headline stuff with silly exaggerations, but phrases which look technical and accurate but in practice are not defined at all, or described vaguely. In a time of aggressive propaganda, this is a serious failure, giving no help when it is most needed. 'Capitalism' is a perfect example, a word always used by Russell in a contemptuous manner. And yet, presumably, any large project needs money if there's any sort of money system.

Russell regarded himself as an innovator: he regarded Prospects of Industrial Civilization (1923) as a pioneering work in sociology. No doubt it's partly due to Jews that writers such as Durkheim and Weber are given priority. And perhaps to British writers that Herbert Spencer is ignored. Russell regarded Power as founding a new science, as Adam Smith is regarded as founding economics. Russell considered that Power had been plagiarised by Burnham (in The Managerial Revolution). Russell complained the final chapters of The Scientific Outlook were plagiarised by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World.

Russell was horrified by the 'Great War'. As with most people, he was at the level of calling it an 'outbreak'. His chapter The First War is worth reading, especially by people who have never heard any arguments against that war. He had no analysis of people who wanted war, and why they wanted war, though he implied he'd kept an eye on Sir Edward Grey and others. But his eyes were on average people:

Most of Russell's information came from newspapers, and if newspapers are owned by people who want war, it's simple to fill the pages with war stories. The Bryce Report state propaganda against Germany, and the prolonged leaks of anti-Russian and anti-German and anti-British material into other countries, clearly showed this. Russell did not talk to ordinary people; I've certainly met people who say they didn't want war at the time. Russell believed that pre-war outbreaks of violence (including those attributed to suffragettes) proved that British society unconsciously wanted war; in fact, it's likely that some of the supposed violence by suffragettes was in fact a Jewish false flag. However, the war gave him a new topic, the part played by impulse in human (and animal) life, which Russell mixed in with Freud, in my view unfortunately.

George Bernard Shaw is represented by five letters to Russell, most relating to the 'Great War'. Shaw loathed it as an evil, a social problem, a monstrous triviality, a vulgar frivolity. He clearly, judging from these letters, had no idea of the forces behind it. Russell had an inkling, but was inclined to blame ordinary people, subjected to intensive propaganda, and, later, call-ups and conscription and two years' hard labour for trying to escape. The general lines of the War as it appeared in Britain show through Russell's pages, but he seems, as far as his autobiography reveals anything, to have been out of touch with belligerents. It's a sad story, but set him up as an out-of-touch useful idiot.

His new topic emerged as Principles of Social Reconstruction (1915):

The first sentence is: 'To all who are capable of new impressions and fresh thought, some modification of former beliefs and hopes has been brought by the war.' Last is: 'Out of their ghosts must come life, and it is we whom they must vivify.'

Russell states that his book on social reconstruction made him a great deal of money (with no figures either of money or copies sold). He was obviously right in regarding the 'Great War', and the 'Russian Revolution', as important; but he ignored serious attempts at analysis of the results—for example, who gained from it, and to what extent the gains were planned. Russell seemed to have been aware of the Bryce Report as a propaganda fake—he wrote a bit about it in his wartime articles. He must have been aware of the 'Balfour Declaration', and was aware that secret agreements preceded the war. I can find no reference to John Reed in Russell's publications; and he dismissed Hilaire Belloc as being 'anti-Semitic'. Despite Russell's theoretical devotion to free enquiry, he failed completely in this critically important test case.

Russell's chapter on 'The First War' reveals him to have been ineffectual—writing articles, addressing audiences. Despite knowing Keynes, and despite his family connections, and familiarity with Prime Ministers, and visits to the USA, his chapter shows his helplessness. The dark side of British, or Anglo-Jewish, power, showed itself in jailings, for himself in the 'first division', and with hard labour and I think consequent death for E D Morel. And in compulsory call-up, when 'popular feeling about the war' proved insufficient. And of course in censorship. And in control over money 'for the duration'. And of course loans. The 1913 Federal Reserve and its other organisations set the stage. Anyone who takes Russell seriously must feel the tragedy of all this: he might have accomplished substantial work in deciphering events, as Europe's aristocrats fell and civilisation retrogressed; but he didn't.

Russell wrote articles throughout the Great War. One was Justice in Wartime, put into a book of essays; but most were I think not republished. He seems to have not taken them very seriously: a TV interview showed him talking about 'sheets' which nobody read. Russell was reluctant to have his writings republished if they showed him in a bad light: an entire 1930s book, Which Way to Peace, was never republished after 1945. I've now (June 2017) uploaded it; click here.

Here are three examples of Russell's ignorances on the 'Great War'. In each case Russell's error was to take the view of war which had been fed to most Britons (but not Jews), and which they hadn't had the brains or energy to analyse:–

- Like many others, for example Hilaire Belloc, he did not trace the roots to the Jewish hatred of Europeans. Jews wanted war.

- Russell thought the war proved that modern techniques were very productive; great productivity was proved by the fact the war went on for years, but people still were fed and clothed. He had no idea about loans in exchange for land, factories, assets: he'd only heard accounts of wars run on a cash-only basis, and had no idea that assets had changed hands (partly of course because the matter of ownership is very hidden and secret). The impoverishment was hidden.

- Russell had no idea of durations of wars: he assumed generals and civil 'servants' and politicians wanted short, efficient, wars. Deliberate prolongation was not on his 'radar'.

Russell often wrote for Jewish publications. It's curious to read (in an essay) that he was aware of the Coudenhove-Kalergi scheme for a mixed race Europe—he was inclined to think it may be a good idea, since of course he blamed Europeans for the slaughter of the 'Great War'.

Chapters II and III deal with Russell's visits to Russia after the Jewish coup, and then China. In the first case, he was an observer. He praised his hosts, but in such a vast territory, and with no Russian, it's difficult to see how he could expect to report reliably in such a land. He might have said he simply didn't know. But intellectuals dislike steps of that sort. Almost incredibly, he met Lenin and Trotsky and other 'revolutionaries'. In just one of his letters he talks of tyrannical Jews.

Russell was very gullible about Jews in the USSR. He writes for example of fish abounding in the Moskva river, but says only fish from trawlers were allowed, since they were industrial. Obviously people fishing would be called 'profiteers' and killed. Only the Jewish 'state' was allowed property—as in the famine in Ukraine. He records shots audible in (I think) Peter and Paul fortress, and thinks 'idealists' were being shot, rather than anyone educated, or rich and non-Jewish, or pro-Russian. He seems to have known nothing of anti-Russian Orthodox killings, and the expansion of Yiddish 'education'. He records how, after WW1 had officially finished, he was in Lulworth Cove, enjoying the scenery, and trying to decide between two lovers, indifferent to any serious concerns.

Russell then visited, and loved, China. ('Once a week the mail would arrive from England, and the letters and newspapers that came from there seemed to breathe upon us a hot blast of insanity like the fiery heat that comes from a furnace door suddenly opened.') He wrote somewhere that China's adopting Communism was inconceivable; in Russia he'd compared Communism with the ideals of Plato's Republic—showing he had no idea how Communism had been forced onto peoples. For that matter, he was surprised by the change in fortunes away from Germany near the end of the Great War—possibly the result of a secret agreement added to Balfour's Declaration giving Russia to Jews. He lectured in China, and his new companion, Dora, lectured on things like women's issues. (Russell realised he 'no longer loved Alys', on a bike ride). Russell's letters are moving and heartfelt, though understandably his grasp of the history of these vast regions was sketchy, mostly nourished by British Victorian history, in which Constantinople, the East India Co, ruination of the Peking Summer Palace, opium, Hong Kong, the Indian Mutiny, and so on were treated in the way distorted modern history is fed to gullible undergraduates now.

Addendum Oct 2017: Russell's visit to China appears to have been about a year—October 1920 to October 1921—and of that time about a quarter was spent in severe illness and recovery). The Chinese Lecture Association invited him, for a year; the previous year had been John Dewey. An online article by Tony Simpson says next year was to be Bergson—perhaps they thought official western philosophers were Confucius-like. And that Russell in his farewell address in July 1921 spoke of China passing through a stage analogous to that of the dictatorship of the communist party in Russia for the purposes of education and non-capitalistic industrialisation. ('Industrialism' ends to be a Jewish word; factories making weapons, slag heaps and ruin, huge prisons, make money for Jews, but not others). It's not clear which parts are verbatim Russell; it is clear that the financing, which must have been Jewish, was of course secret. Russell never succeeded in separating 'capitalism' from 'finance': in practice, non-Jews relying on the fluctuating Federal Reserve Jewish lending policies were evil capitalists, while Jews printing money ad lib to suit themselves and finance wars were respectable financiers. No wonder Russell received a note after his departure from China very politely chiding him for giving no useful advice.

Russell seems to have had not the slightest insight into realities of money; it's possible it was far more secret even than now. Just a few examples: In Korea at that time a Christian was practically synonymous with a bomb-thrower. Really? Sounds like Jews to me. And I also had a seminar of the more advanced students. All of them were Bolsheviks except one, who was the nephew of the emperor. They used to slip off to Moscow [in 1920!] one by one. I'd take a large bet they were puppets of Jews, perhaps even the 'Kaifeng Jews', a taboo group of course. Russell says The National University of Peking was very remarkable, the Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor both passionately devoted to the modernising of China. This despite the 'funds which should have gone to pay salaries were always being appropriated by Tuchuns ['provincial military governors'] so that teaching was mainly a labour of love. Well, there are lots of teachers like that, aren't there?

A reprinted letter from Johnson Yuan (Yuan is not on the list of 7 Sinified Jewish names I've seen) could not I think be the original invitation; he wants knowledge of Anarchism, Syndicalism, Socialism etc to be acquired, his letter written after Russell arrived in Shanghai. Anyway, a point which puzzled me is explained: Russell's works so far had been mainly in geometry, mathematics, and philosophy, and of course plenty of those might have been invited to China. He wrote against the 'Great War', but said nothing very helpful. His works on Social Reconstruction must have been the target. Russell mentions the Rockefeller Foundation as intellectual enemies. Probably in fact Russell was invited and paid as a useful idiot, conveying nothing. He writes all but nothing of his lectures and speeches, while much of his part-chapter talks of beautiful scenery, witty Chinese, impressive banquets, hotels elegant and otherwise, vicious British officialdom, Dora Black's pregnancy.

Aged almost 50, Russell never acquired more knowledge of China; he did nothing for the millions of deaths claimed to have been under 'Communism'.

The second parts of Volume II deal with Russell's second marriage, and a school Russell tried to set up in Telegraph House, an obsolete building which he bought from his bankrupt brother. This was a great period for experimental schools, because the memories of 19th century paying schools (H G Wells wrote on this) were still alive. There was scope for a combination of business with idealistic education. Russell never seems to have thought of founding or jointly founding a new university. Taxation, and legal restrictions, are now so high that perhaps home-schooling will become the 21st-century equivalent. Musing over Russell at the time, writing newspaper columns and collections of essays, and a potboiler or two, in a school he couldn't manage, trying to write great books and short of money, suggests he was at the nadir of his fortunes. His history of the 19th century Freedom and Organization: 1814-1914, written in two parts Legitimacy vs Industrialism 1814 to 1848 ('Industrialism' is used by Jews to suggest progress) and Freedom vs Organization 1776 to 1914 (1934), shows his struggle to make sense of the world whilst omitting the Jewish issue. Russell's literary non-starts are not stressed in his autobiography, but it's clear from McMaster University Archives that he tried, and failed, to write on 'fascism'. He said in a TV interview (not in his autobiography) that he had a new idea for a book almost every day.

Russell was invited to the USA to take up an academic position. If there were retirement and pension implications, Russell doesn't state them, though he does of course discuss his adventures when opposition was stirred up in the 'chair of indecency' Catholic incidents. At the time, New York had been spared the huge immigration of Jewish 'refugees', whose fraudulent claims provided them with a model for subsequent nonwhite invasions. Russell spent his time until the end of the Second World War in the USA. It's clear from his letters that he had no clue about Hitler or the Second World War.

During Russell's time in the USA, arms were shipped to the USSR in huge quantities, largely secretly as not everybody liked Stalin. Bear this in mind when reading Volume II. Russell isn't very clear on the 'phoney war' before 1941, or on the way Jews fixed up war against France, Germany, and Italy—and in effect eastern Europe, by supplying Stalin—and took part in the 'civil war' in Spain. Maybe this Anglo-American action will eventually produce a European backlash and revenge.

The final part of this volume has Russell working on History of Western Philosophy, as Jewish influence over the world sank deeper. Russell had theories on the rise and fall of civilisations and worldview: 'Three cycles: Greek, Catholic, Protestant. In each case.. decay of .. dogma leads to anarchy and thence to dictatorship. I like the growth of Catholicism out of Greek decadence, and of Luther out of Machiavelli's outlook'. This may have been related to the feeling of insecurity of a world amid a huge war—though very few people could explain why a tiny country like Germany should be taken so seriously. Thus Gilbert Murray, in typical confusion, to Russell: '.. not quite clear what the two sides were: Communism or Socialism against Fascism.. Christianity against ungodliness. But now.. Britain and America .. against the various autocracies, which means Liberalism v Tyranny..' Russell was not very secure in these categories. He was comfortable with philosophers and their schools, largely because some sort of consensus had been decided upon. But, despite his efforts, he never found convincing historical impulses and motives, as his book Power shows. Nor of course did for example Toynbee, at more or less the same time.

History of Western Philosophy can now be seen to be marred by errors, all to do with misunderstandings of Jews. No doubt others will become clear, for example related to science. Anyway, by Volume II Russell was convinced that Rousseau and Romanticism had led to 'Fascism'—Russell never seemed to use the expression 'NSDAP'. The NSDAP's name being a socialist workers party, and Russell advocating 'socialism', must have been a problem for him. However, the Labour Party leadership in Britain had decreed that Hitler was not left wing, after all, but right wing. Russell was primed to announce Rousseau 'led to Auschwitz' though this phrase is not present in History of Western Philosophy.

The reprinted letters following Chapters 12 and 13 (1930-7, 1938-44) light, one must assume, Russell's states of mind and activities when he was in his 60s, and well-known in the world. One from Einstein (1931), after flattery, recommends 'an international journalistic enterprise (Cooperation) to which the best people all belong as contributors ... to educate the public in all countries in international understanding. ... Dr J. Révész, will visit England in the near future..' [Original in German.] Russell's reply as printed merely invited Einstein to visit; probably this was just a small subsection of Jewish propaganda for Jewish control, which of course worked: Jews won the Second World War. Russell commented in the Tom Mooney case—no doubt a media-promoted thing.

[And described by David Irving in a video The Manipulation of History as one of many cruel, murderous Jews.]

Here's another account:

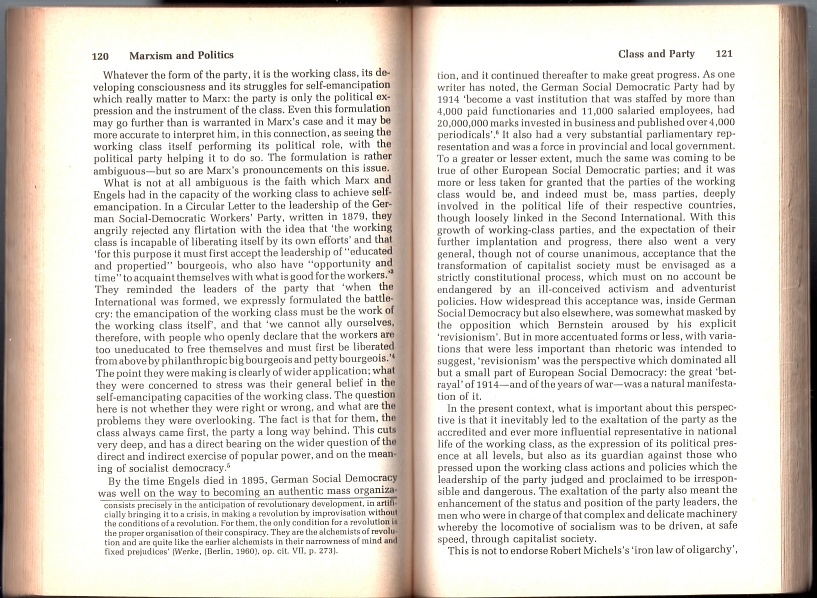

Matyas Rákosi (born Rosenfeld), de-facto jewish ruler of Communist Hungary, was part of jewish Bela Kun’s doomed government in 1919 but fled to Russia after Soviet Hungary’s collapse. He then became the Cominterm leader and returned to Hungary as dictator propped up by Joseph Stalin when Hungary fell under communism after WWII.

No doubt, for those Hungarians who lived through the Communist Era, it was common knowledge that Jews like Rakosi dominated The Party, but to state so publicly was suicidal considering it was a capital offense.]

It's clear Russell had no idea about the machinations intended to lead to world war. A large chunk—in my view, far too large—of the later letters deals with the City College of New York issue, in which an offer of a professorship was withdrawn—this is reminiscent of manufactured outbreaks of scandals in US education, which of course still happen. A letter from the 'Student Council' is enclosed; I'm sure Russell never got to the bottom of what happened, though he thought (as he said on early TV) it was a 'Catholic thing'.

At the end of his Chapter 9, 'Russia', (BR never seems to have used the expression 'Soviet Union'), here are 7 letters from Harold Laski in Harvard in the USA, 5 of them more or less consecutive from Aug 1919 to Jan 2020. They seem an example of the manipulations of fellow-Jews to get their people into controlling positions.

Volume III 1944-1967

Volume III 1944-1967After the success of the first volumes of Russell's autobiography, there were problems with this. (Note: volume 3 is still not downloadable, in 2018). It seems the American publisher declined to publish. (I don't know any contractual or other details, though clearly the appearance of homogeneous external appearance of the volumes is misleading). Anyway, it was published eventually, though there seem to be traces of carelessness—Fennimore Cooper, Ralph Milliband, and Pablo Cassals suggest sluggish proofreading. (A tape-recorded transcription elsewhere of Russell has 'Bishop Bluebroom' for Brougham—perhaps proofreaders preferred simpler stuff). The problems were with war crimes and atrocities, which of course the Jewish media censor. The final quarter-century of Russell's life included his activism against the 'West'—Russell knew nothing of ZOG, except, just possibly, at the very end of his life. Certainly this volume is very much unlike the author's preceding volumes. Russell records his reactions to public events: the Second World War, the Cold War, the BBC, nuclear weapons, the Korean War, Kennedy's murder, the Cuba Crisis, the Vietnam War. Chapter III - Trafalgar Square looks at protests against nuclear weapons. Chapter IV - The Foundation is on the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

That at least is the formal version. Russell probably had no idea about Eisenhower (Jew from Sweden) starving Germans after the war. Or the fraud of what was later called 'the Holocaust', curious Greek expression as it is. Or the BBC frauds, of which the plump and oily Dimbleby, a Jew from London, started anti-German post-war propaganda in earnest. Or the fact, suppressed for decades, that mail bombs were sent to Labour Party leaders by Jews, over Israel. Russell had been to Germany: he accepted the figure of 135,000 Germans destroyed in the razing of Dresden, 'but also their houses and countless treasures'. 'By giving part of Germany to Russia and part to the West, the victorious Governments ensured the continuation of strife between East and West, particularly as Berlin was partitioned and there was no guarantee of access by the West to its part of Berlin except by air.' Note Russell's assumption that the Governments, all of course known now to be Jewish controlled, wanted to stop strife. He must have been laughed at, for his gullibility.

Important note on which issues were taken up by protestors: Jewish misdirection encouraged timewasting on a vast scale, on issues now known to be non-existent, including 'Communism' and 'Nazism' and 'Italian Fascism' as spontaneous movements, nuclear weapons, the JFK 'assassination', the fake Holocaust of Jews, the moon landings. 'Climate change' mostly post-dated Russell. Rather pointless disputes over religion concealed the rent-collecting and fact-suppressing aspects of established religions.

Russell made a public announcement that Stalin's USSR should be invaded. He later denied his words, but the important point is that Jews in Russia felt they had to pretend to 'explode their first bomb in August, 1949'. Perhaps readers who have not met the nuclear revisionist view before might reread the above few sentences. A typical example of Russell's activism was his campaign on the Cuba Crisis—clearly at this distance a fake rigged up by Jews, along with the marrano Castro. About a year later, Kennedy was murdered (or allegedly murdered); again there's a Jewish link. (The Who Killed Kennedy? team included Mark Lane, a Jew, and Victor Gollancz, a lifelong propagandist for Jews. It's unlikely they would ever investigate seriously, of course).

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Russell was lonely and rather isolated. He says himself that after the war, Cambridge ladies thought he and his wife were 'not respectable'—you'd imagine they might have had other things to think about. Rupert Crawshay-Williams is my source for the 'loneliness' of Russell. His friends from youth had largely died. Alan Wood (who wrote on the then-notorious money-wasting groundnuts scheme) and his wife became friends; but Wood died, after writing a biography of Russell.

Russell's lifelong ignorance of Jews is clearer in (for example) Ronald Clark's Life. In 1945, the Jew propagandist, publisher and liar Victor Gollancz, 'leader of the "Save Europe Now" campaign', wrote to Russell: '.. the meeting may be given the character of an "anti-Bolshevik crusade" in the bad sense. I am told that already, as a result of the things they have seen, a lot of soldiers in Berlin are saying "Goebbels was right"; we don't want that sort of development.'

Russell's public views appeared on BBC radio as the first Reith Lectures, in 1948, a series of six, Authority and the Individual. Probably suggested by Sir Arthur Keith, and by nuclear myths, part of his talk stated that war had been a leading cause of innovation—very probably the reverse of the truth. Russell took little effective interest in the 'United Nations', unfortunately. For example, one of its foundational bases was the idea that races were of no importance—naturally, Jewish input was important here. Russell therefore was weak on actual possible world government, which he considered essential, since he swallowed the myth of nuclear annihilation. Volume III has Russell meditating on the future: the population problem. And 'economic justice'. Russell, misreading the world, thought political democracy applies in industrialised countries, no doubt accepting the Jewish view; but economic justice is 'still a painfully-sought goal.' Fascinating to read this elderly man's lucubrations on likely events of the next few centuries, especially, now, from a revisionist viewpoint.

Russell was given a Nobel Prize (for Literature) in 1950—most of which went in alimony payments, he writes here. Nobel Prizes are of course something of a joke; probably it had been decided that Russell's support for WW2 was worth a bit of cash. Among other things, Russell in 1952 visited Greece, troubled by the US Army; 1953, Scotland; 1954, Paris; in 1955 made a speech in Glasgow for a Labour candidate (which Alistair Cooke, a BBC hack from Salford in northern England, wrote about). This period was enlivened by philosophical disputations; Russell disliked linguistic philosophy, with 'common usage' one of its slogans, and Russell has accounts of his disputes. He seems not to have realised that Oxford philosophers might feel out of their depths in a world of nuclear weapons and mass murder of Jews, in which in retrospect they must have been laughed at, by politicians in the know.

And in 1955, Russell tried to get 'eminent scientists' to make a statement calling for joint action; Neils Bohr, Russian Academicians, Otto Hahn, Lord Adrian and others refused, and there was no reply from China. Josef Rotblat agreed to act as Chairman; I believe he was a Jew from Hungary. Looking back, he must have been part of the scheme to pretend Jews had nuclear weapons. In 1957, Cyrus Eaton, a Jew in Canada, put up money for a meeting in Pugwash. It can be seen that Jews were circling, just in case. (Note that Herman Kahn invented or popularised the word 'megadeath': I wonder if this was a leftover from the Jewish victory in the second World War). Ralph Schoenman is reported to have met Russell in 1960, the story being he hitch-hiked there; but who knows?

Russell's Autobiography mentions his affection for Victor William Williams Saunders Purcell (1896–1965), 'a Government administrator in South East Asia' [probably Malaya] and Don at Cambridge. 'I did not even begin to know him till he was drawn into discussions with us about the Foundation's doings in relation to South East Asia. ... it was not until May, 1964, that we really came to know each other...' They only really knew each other for about 9 months before Purcell's death. It struck me that perhaps he was part of the control being applied to Russell.

The Foundation: Russell's first speech to members of the Vietnam War crimes Tribunal was November 13th, 1966. This met some ridicule from the Jewish media; I doubt if anyone yet has researched into archives of (for example) the New York Times. Russell was uncomprehending about the Jewish media: newspapers exist to facilitate truth, and improve the world; surely that's an obvious ethical ground rule? Russell uncomprehendingly faced the Jewish liars of the world, to whom bombs meant money and young Vietnamese girls raped were good for a Jewish laugh. I think his letters to the New York Times were the first occasion in which he was faced with people genuinely and unblushingly favouring evil: destruction of Vietnamese landscape, bombing villages, large-scale rape, chemical warfare etc. The sort of thing that caused Robert Faurisson to say the USAF killed more children than any other organisation. Russell had no idea that so-called 'Jews' were evil, wanted to be evil, and liked being evil. His verdict on the destruction of Vietnam was pitifully innocent, and utterly non-aware of Jews: The Press, the military authorities, and many of the American and British legal luminaries, consider that their honour and humanity will be better served by allowing their officers to burn women and children to death than by adopting the standards applied in the Nuremberg Trials. This comes of accepting Hitler's legacy. It's now known by many that, of course, it was Jewish legacy, and here's my extra note–

[1] Nuclear Weapons.

[2] Persecuted minorities.

[3] Persecuted individuals and liberation of prisoners.

[4] 1963 Foundation formed, probably by 'Hungarian Jew' Ralph Schoenman. With Christopher Farley and Pamela Wood. Offices, secretaries, fact-finders, representatives, correspondents etc.

[5] 1963 JFK

[6] 1965 Russell's speeches against Harold Wilson and Britain's "Labour Party".

[7] 1966 Vietnam War: International War Crimes Tribunal

[1] Nuclear Weapons. Russell believed the entire propaganda message on nuclear weapons, and considered himself qualified to discuss them. He must have unwittingly become part of the propaganda process. Rotblat, Cyrus Eaton, Herman Kahn, Edward Teller, and many other Jews were part of the circus. How many members of the public were sceptical remains a secret, though probably Jewish public opinion samplings could provide some insight. Russell's chapter begins with his assertions about "self-preservation", and this (according to Russell) "trumped by the desire to get the better of the other fellow". Russell of course was naive about the entire Jewish technical faked superstructure. He believed in US search for raw materials and markets, for example cobalt which (Russell thought) could be used in a 'cobalt bomb'. Russell had no idea that Jewish profits from weapons, takeover of central banks, plus imposition of rents, could be far more lucrative: He was a perfect model of the type who sucks up to the rich, without determining where the riches come from, as described by Hilaire Belloc. Russell gives a puzzled account, in his section on financial begging: ... we [met] only once with virulent discourtesy. This was at a party of rich Jews given in order that I might speak of our work for the Jews in Soviet countries in whom they professed themselves mightily interested. Unfortunately, Russell doesn't say what the rich Jews said. And he doesn't say why Jews predominated in the Foundation; were there really so few honest whites in the world?

Cold War—Russell believed in the Cold War (and Cuba as a 'Communist' country) just as advertised in the Jewish media. Today, it's far more obvious that Jews controlled both the USA and USSR.

[2] Persecuted minorities. Russell mentions the Naga—still a live issue; they are being flooded by Bengalis. He also mentions 'Gypsies'. But on the whole there are few of these; certainly not whites, for example. Of course the Jew media approach only considers Jews, and Russell, with an almost comic ignorance, was concerned with Jews in the Soviet Union! ...

[3] Persecuted individuals and liberation of prisoners. ... Russell often championed individuals, generally with the most extraordinary indifference to what they had done. One gets the feeling that if Stalin had been found in prison, Russell would have responded to a letter pleading for the release of this long-term activist, with, admittedly, an uneven history. He lists a Jew from Germany, wanting to get an English girl pregnant; a Pole, or perhaps Jew, writing obscene verse; Greeks described as 'Communists, I'd guess Jew collaborators; Palestinians, described by Russell as 'refugees'; Jews in the USSR—'I began to make appeals on behalf of whole groups'; Sobell, the fake nuclear spy—but, if his story were true—might have imperilled the entire human race; Heintz [sic] Brandt. Even the notorious killer Jew, Rákosi.

[4] 1963 Foundation formed, probably by 'Hungarian Jew' Ralph Schoenman. Secretaries, fact-finders, representatives, correspondents etc. Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation (company limited by guarantee), and Atlantic Peace Commission (the latter a charity).

[5] 1963 JFK Russell lists (in about 9 pages) '16 QUESTIONS ON THE ASSASSINATION'. He was of course ignorant of the pattern of Jewish assassinations and violence through the ages. He was of course also ignorant of media-driven false flags and campaigns of lies.

[6] 1965 Russell's speeches against Harold Wilson and Britain's "Labour Party"

[7] 1966 Vietnam War: International War Crimes Tribunal. Russell talks in the final five pages or so, before the letters section, of his book War Crimes in Vietnam, which is not reprinted (2018) by his supposed trusts. Russell says it sold out, and was widely translated, but gives no sales figures. Here are the relevant pages from his autobiography:

Note how Russell, under the influence of post-1945 Jewish propaganda, always blames Germans and Japanese: '... [pretexts] reminded me of nothing less than those offered ... for Hitler's adventures in Europe ...' and '... American conduct in Vietnam as barbarism 'reminiscent of warfare as practised by the Germans in eastern Europe and the Japanese in South-East Asia'.

Russell's letters and appendices say more about the Vietnam War. The biography of 1975 by Ronald W Clark gives more information, including Russell's 'Private Memorandum concerning Ralph Schoenman'; the final portion states that Schoenman stated that all Russell's major initiatives since 1960 were Schoenman's work, 'in thought and deed', which Russell describes as 'preposterous' and perhaps 'well established in megalomania'. However, it may be truer than Russell thought: the 'Committee of 100' started in 1960, and it now appears that nuclear weapons were a hoax, and e.g. Cuba was controlled all the time. It's easy to imagine Schoenman selecting misinformation to feed to Russell, in (for example) Has Man a Future? published in 1961, and Unarmed Victory, published in 1963, on the 'Cuba Crisis' and Sino-Indian dispute. According to Clark, Schoenman's behavior (which included a lot of unexplained absences) became erratic and insulting as the War Crimes Tribunal took shape.

But note that Russell never, ever, separated the idea of a state or nation from the internal Jewish influence. No doubt the Vietnam War was a takeover by Jews; to this day as far as can be determined Jews control the money, and also control war crimes information—the opposite policy to their Holohoax fraud. He really thought some countries were 'Communist', for example.

Jews gathered round and controlled poor Russell's Foundation. Vladimir Dedijer was probably a Jew activist claiming to be a Serb; Isaac Deutscher wrote a junk biography of Stalin; Noam Chomsky issued statements mainly about Jews, and his later record on e.g. 9/11 and Kennedy proves his rôle was to obstruct and evade. Victor Gollancz corresponded with Russell (says Ronald Clark—himself of course a gullible paid-by-advances writer, who even wrote on Einstein); Barry Feinberg was an editor; Anton Felton was an accountant for Russell; Cyrus Eaton in Canada kept an eye on nuclear discussions; the New York Times censored him; so did the BBC. A large proportion of the writers in the Foundation's London Bulletin were Jews.

Looking back, it's clear a large part of Jewish activity was propagandist, and aimed to conceal Jewish wars and mass killings.

Jewish wars are not between nations or states, as is advertised, but to make money for Jews by control of weapons and equipment by finance, and making money from loans, usually to governments or 'governments', and controlling issue of money, with the bonus of maiming killing goyim and destroying creative achievements such as splendid cities. None of this is present in Russell. (It's just possible, though very unlikely, that John Russell ('Lord John Russell'), could have lived long enough to tell young Bertrand a thing or two). His speech to his tribunal was three or four years after his epistolary exchange with the Jew York Times. His book War Crimes in Vietnam remains discreetly unpublished by Routledge, his posthumous publishers, presumably picked by his Foundation. All this activity by Russell causes me to doubt Russell ever considered himself a Jew, something which has been suggested. I see why they say it; and why judging from published books it's credible. But I don't think it's true; he was just a Briton being polite and Christian to a few racially outlandish oddities. But he did follow the convention of secrecy about Jews: if there were any in his family tree, as is likely enough, he said nothing of them in his autobiography.

The main office or centre of the B.R.P.F. was established in Nottingham. Certainly atrocity accounts from Vietnam were known in Nottingham University. There were student actions in 1968, which have subsequently been presented by the Jewish media as hippiesque 1960s self-indulgence, and many people considering themselves politically aware have no comprehension of the underlying issues. Most of the activists were Jews, and most non-Jews at the time had no idea of this; and Jewish motives were mainly to hide the truth of creatures like Kissinger, and to hold on to money Jews made from war. The BRPF was a Jewish front from the start; just the list of their writers makes this plain enough. Probably revisionist re-examinations of the 1960s will correct the media mirage which has been assembled. But the picture largely remains intact: Richard Dawkins' autobiography, for example, shows complete ignorance of that time.

Looking again at Russell's conclusions drawn from his long life, we find: Consider the vast areas of the world where the young have little or no education and where adults have not the capacity to realise elementary conditions of comfort. These inequalities rouse envy and are potential causes of great disorder. Whether the world will be able by peaceful means to raise the conditions of the poorer nations is, to my mind, very doubtful, and is likely to prove the most difficult governmental problem of coming centuries. Russell used the expression 'third world' in his Autobiography, perhaps borrowed from Schoenman, I'd guess. But he left the problems to others: he believed 'the techniques are all known' for general prosperity; but he expressed no views on the genetic ability of populations, or the availability of raw materials and energy to move them around.

His final paragraph is about the 'The essential unity of American military, economic and cold war policies was increasingly revealed by the sordidness and cruelty of the Vietnam war. ... Most difficult for many in the West to admit.' Russell faced opposition, but never fathomed the truth about Jews and their collaborators.

After his Autobiography, Russell continued his activities as best he could. Dear Bertrand Russell was extracted from his archived letters, but edited by two Jews. His last published statement was on Israel's expansionism. His The Entire American People Are On Trial was published posthumously in March 1970. Russell's Autobiography is a landmark on the road to reversing several centuries of evil. It is well worth reading in entirety. He was not completely honest; and he missed some important truths, to such an extent that he might legitimately be regarded as worthless. But he has one thing which Jews and their allies can never have: they will never be able to present their lives, as truthfully as they can, to genuinely interested audiences, in the way Russell does.

RUSSELL, BERTRAND, ed. Feinberg, Barry: THE COLLECTED STORIES OF BERTRAND RUSSELL [1972]

Not just stories, but some other writings. Collected by the Jew Feinberg, who seems to have made some sort of living out of Russell, and presumably had met him.

The book is by now probably online, for example in archive.org, but I recently noticed I made notes on it many years ago. These notes include transcriptions of FAMILY, FRIENDS AND OTHERS (made from tape; about 1959) and READING HISTORY AS IT NEVER IS WRITTEN also from tape.

The transcriptions from tape contain a few errors; square brackets enclose my corrections, where I found them.

Russell is at his absolutely characteristic; he assumes non-aristocratic great men, and popular movements, come from nowhere, and has no idea about the activities of groups of people. It is saddening to perceive his lack of insight. But anyway here he is.

FAMILY, FRIENDS AND OTHERS

My paternal grandmother, who was a daughter of Lord Minto, had many interesting and some amusing reminiscences which it was rather difficult to elicit . she had to be coaxed to tell them. Her mother's father was a certain Mr Brydon who wrote a book called Travels in Sicily and Malta in which he advanced the terribly rash opinion that the lava on the slopes of Etna was so deep that it must have begun to flow before 4004 B.C. On account of this heresy, I regret to say, he was cut by the county. Nevertheless, one of his daughters married my grandmother's father, and her sisters came to live at Minto. On one occasion, after a good deal of coaxing, my grandmother told me that one of her aunts was rather vulgar. I said, 'In what did the vulgarity consist?' 'Well, she always had two eggs for breakfast, and she would look round the breakfast table and say "Who's eaten my second egg?" ' They were always boiled eggs and her vulgarity consisted in having two. Such was the effect of this story upon me that never throughout a long life have I been able to eat two boiled eggs for breakfast, though I can quite easily eat two poached eggs or two scrambled eggs or two eggs in any other way. But this story made it impossible for me to eat two boiled eggs for fear my descendants should say that I was somewhat vulgar.

I asked her whether she knew Sir Walter Scott. Abbottsford was in the immediate neighbourhood of Minto where my grandmother passed her girlhood. She told me that she only met him once, and that the reason she met him so seldom was that there was a feud between the Elliots, my grandmother's family, and the Scotts, who were the great family of Roxsboroughshire. This feud was taken on by Sir Walter Scott, and it was thought he had no right to take it on because he was not really at all closely related to the Scotts of Roxsborough; but he did take it on, with the result that she only met him once.

She told me once about an incident when her grandfather had been appointed Governor-General of India, and his wife was looking out for a chef who would be suitable for such an exalted situation. She interviewed one chef, who demanded two hundred a year. 'Why,' she said, 'that's as much as many curates get.' 'Ah, yes,' said the prospective chef, 'but you forget the mental work in my profession.'

She used to tell macabre stories sometimes, almost always somewhat derogatory of conjugal affection. Her worst of these stories was the story of an old couple who had lived in the closest harmony for many years, to the admiration of all their neighbours; and at last the wife died and was

265

Anecdotes

put into the coffin. And as she was being carried downstairs, the coffin bumped against the corner and she revived. And they lived again happily for many years. At last she died again, was put into the coffin again, and as it was being carried down, the bereaved widower remarked: 'Take care not to bump against the corner.' This was the sort of story that she liked. I do not know quite why.

There was another story that she used to tell about a Scots girl called Maisie, who had very beautiful golden hair and in addition had a golden leg; and when she was buried, some very very wicked man rifled the grave and took away the golden leg. The next night as he was sleeping Maisie appeared before him and he said, 'Maisie, Maisie, whar is yer beautiful blue e'en?' and she replied, 'Mouldering in the grave.' And he said, 'Maisie, Maisie, whar is yer beautiful goulden hair?' and she said, 'Mouldering in the grave.' And at last he said, 'And Maisie, Maisie, whar's yer beautiful goulden leg?' 'Here, you thief!' At this point he gave up and restored the leg to its proper grave.

There was a story about my grandfather which illustrated, perhaps, a certain lack of such a tact as one might have expected. He was at a dinner-party, and after dinner when the gentlemen returned from the dining-table, he sat beside the Duchess of A. But after sitting beside her for some time he got up rather suddenly and walked across the room to the Duchess of B and sat beside her. When he and his wife got home, his wife said to him, 'Why did you so suddenly leave the Duchess of A?' and he said, 'Oh, because the fire was too hot and I could not bear it.' She said, 'I hope you explained to the Duchess of A.' 'Well, no,' he said, 'but I explained to the Duchess of B.'

At a time when my grandfather was Prime Minister, a terrible misadventure once befell him at the Lord Mayor's banquet. The Lord Mayor had received a very magnificent silver snuff-box, which was a gift from Napoleon III, and as he was showing it to my grandfather he said, 'You see it has a hen on it.' My grandfather, who wasn't looking at it very closely, said, 'Oh, I should have thought it would have been an eagle.' And on looking again, he saw that it was not a hen but an N. The rest of the dinner had to go on after this misadventure.

When I was six years old my grandmother took me to stay at St Fillans in Perthshire, and one day we went on a very long drive to Glenartney. I got rather bored with sitting still for such a long time and I was being amused by little rhymes; one of which was 'When you get to Glenartney, you'll hear a horse in a cart neigh', and when we got to Glenartney, sure enough, we did hear a horse in a cart neigh. I have often wondered since whether the Lord Macartney was a son of the Glen. But as to this I have never been able to ascertain the correct genealogy.

My paternal grandmother was a very patriotic Scots woman; and she told me that when she was a girl it was the practice at Christmas-time for

Family, Friends and Others

the village people to come up to Minto, where she lived, and perform little plays and songs, rather in the style of Bottom in Midsummer Night's Dream. These all had a patriotic tone about them. There was one in which a boy came forward and professed to be Alexander the Great, and said 'I am Alexander, King of Macedon / Who conquered all the world but Scotland alone. / But when I came to Scotland my blood it waxed cold / To find so small a nation so powerful and so bold.'

My grandfather established a village school in Petersham, which was his parish, at a time when such schools were still uncommon. My grandmother went to ask the children questions that were intended to test their intelligence, and one of the questions she asked them was 'Did you ever see a Scotchman?' And one of them cried, 'Yes, Milady, once at a Fair.' Then she went on to say 'Was he white or black?' 'Oh, black, Milady.'

When I was two years old my grandparents rented Tennyson's house, Aldworth, for the summer months, and I stayed with them. They used to take me out onto Blackdown and they taught me to recite, 'O the dreary dreary moorland; / O the barren barren shore, / O my Amy's shallow hearted, / O my Amy's mine no more.' / I am told, and I can well believe it, that the effect was irrestibly comic.

We often hear the phrase, 'old world courtesy', and I think that probably a good many people doubt whether there ever was such a thing. I think I can give two illustrations, both of which happened to my grandfather. My grandfather's nephew, Lord Odo Russell, afterwards Lord Ampthill, had had an interview with Napoleon III, shortly after Napoleon's rise to power. My grandfather asked him what he had thought of Napoleon III and he said: 'I thought that he was thinking, as I was, that he was the nephew of his uncle.' It seems to me that this was one of the most flatteringly polite remarks that I have ever come across. There was another example of the same thing, which was when the Shah of Persia was caught in a rainstorm in Richmond Park and took refuge in my grandfather's house. My grandfather apologised for the smallness of his house: 'Yes,' said the Shah, 'it is a small house but it contains a great man.' I think these examples show that old world courtesy really did exist.

When my parents visited America in 1867, my mother noted a few occurrences in her diary. There are three of these that seem somewhat interesting. One was when they went to see a well which Berkeley had visited, while he was on his abortive journey to the West Indies; and my mother played with the bucket of this well in a manner that was thought irreverent by Berkeley's admirers who had taken her to this place. The second occasion was, I found, still remembered when I went to America nearly thirty years later. There was a very fine dinner-party arranged for my parents and they provided terrapin which was considered a very great delicacy. My father, who was somewhat conservative in his eating habits, 267

Anecdotes

refused, whereupon my mother shouted along the length of the table, 'Taste it, Amberley, it's not so very nasty!'

This was still remembered with horror when I was there in 1896. The third incident which is recorded in her diary is another dinner-party in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She says, 'I sat between Mr So and So and Mr Longfellow, the poet. I liked Mr So and So.' Of Mr Longfellow she says nothing whatever.

Some occasions, when I was a child, filled me with somewhat bitter disappointment. On one occasion after we had been talking about cannibalism I heard my people say to each other: 'When is that Eton boy coming?' and I thought they meant a boy who had been eaten. When he turned up, and was a perfectly ordinary boy, it caused me the most profound disenchantment. But that was not the worst. The worst instance was when I heard them say to each other, 'When is that young Lyon coming?' And I said, 'Is there a lion coming?' 'Oh yes,' they said, 'and you'll see him in the drawing-room and it'll be quite safe.' And then they came and said, 'The young Lyon has come,' and they ushered me into the drawing-room and it was a completely conventional young man whose name was Lyon. I burst into tears and wept the whole of the rest of the day, and the poor young man couldn't imagine why.

My first contact with Robert Browning was when I was two years old. He came to lunch with my people and brought with him the actor Salvini. Everybody was used to Browning, but Salvini was more of a rarity, and they would have liked to hear him speak. But Browning talked the whole time without stopping. At last, unwittingly, expressing the feelings of the company, I said, 'I wish that man would stop talking.' I had, of course, to be hushed very quickly, but he did stop.

I was kept to very spartan fare in the matter of eating when I was a boy. It was thought that fruit was absolutely disastrous for a child and he must never be allowed any. One time after we had all had pudding, the plates were changed and everybody except me was given an orange. I was given a plate but I was not given an orange. I remarked plaintively, 'A plate and nothing on it.' Everybody laughed-but I didn't get an orange.

My cousin, G. W. E. Russell, who was something of a gourmand, was dining once with my people and expressed a very strong preference for one dish rather than another. I also had the same preference but I was compelled to have the dish that I didn't like and was told: 'You must not have your little likes and dislikes.' And I said, 'Cousin George has his little likes and dislikes.' Again I was quickly hushed, but I never was able to see the justice of it.

I had an uncle, Rollo Russell, who was very good at explaining things to children. I asked him one day why they have stained glass in churches, and he said 'Well, I'll tell you . long ago they didn't, but one day, just as the parson had got up into the pulpit and was about to begin his sermon,

268

Family, Friends and Others

he saw a man outside the church walking with a pail of whitewash on his head. And at that precise moment the bottom of the pail fell out and the man was inundated with whitewash. The poor parson could not control his laughter and was unable to go on with his sermon. So ever since they've had stained glass in windows.'

My cousin, St George Lane Fox, afterwards Fox Pitt, was a very singular character. While a very young man he invented electric light before Swann and Edison had thought of doing so. He then got religion, not in the form which is usual in the West, but in the form of esoteric Buddhism. This caused him to think that he should occupy himself no longer with mundane affairs, and he went to Tibet to visit Lamas and to learn all the niceties of Buddhist theology. However, after a certain length of time in Tibet he decided to come home again, and he then discovered to his disgust that Swann and Edison had been making electric light. He brought actions against them, a number of actions, all of which he lost, and in the end he was reduced to bankruptcy. But he consoled himself with the tenets of esoteric Buddhism and thought that after all a man should be able to do without a plethora of worldly goods. He then had an experience which shows the dangers of book-learning. He married a sister of Lord Alfred Douglas. On his wedding night he was overheard saying: 'I must go and look it up in the book,' and shortly afterwards he was heard saying, 'It sounds quite simple.' However, very shortly afterwards there was a nullity.

My great-aunt, Lady Charlotte Portal, had various claims to distinction. Her latest was that she was the grandmother of the only man who holds both the Garter and the Order of Merit. Her earliest claim to fame occurred when she was a very small child. She tumbled out of bed, failed to wake up, but was heard muttering: 'My head is laid low, my pride has had a fall.' She was sometimes a little inapt in ways of expressing herself. On one occasion when she was starting for the Continent, her. footman, whose Christian name was George, came to take her luggage to the train, and just as the train was starting it occurred to her that she might wish to write to him about some matter of business, and that she didn't remember his surname; so she put her head out of the window and said: 'George, George, what's your name?' George touched his hat and replied: 'George, Milady.' By that time the train was out of earshot and the thing was irremediable.

My sister-in-law, Elizabeth, was once staying in a Swiss hotel where the partitions were somewhat inadequate. The room next to hers was occupied by a middle-aged American couple. She heard them coming up to bed and conversing animatedly for a time, then, there was a long silence, interrupted at last in a severe feminine voice, 'Henry, is it because you won't, or because you can't?'

Another sister-in-law, when she became engaged to my brother, was brought to lunch with my grandmother, who practised the strictest Victorian propriety. The girl was shy and behaved with a pretty restraint until near 269

Anecdotes

the end of lunch when, unfortunately, there came a thunderstorm. The thunder got louder and louder and at last there was an absolutely deafening clap. She leapt from her seat, exclaiming 'Golly!' My grandmother had never heard the word, but very justly concluded that if it had been a suitable word for young ladies, she would have heard it.