Most Reviews More reviews, by subject:- Film, TV, DVDs, CDs, media critics | Health, Medical | Jews (Frauds, Freemasons, Religions, Rules, Wars) | Race | Revisionism | Women | Bertrand Russell | Richard Dawkins | Martin Gardner | H G Wells

The History of the Fairchild Family by Mary Martha Sherwood.

And Other Victorian Christian Books.

Review by Rae West 30 Jan 2020

Interlude: Watching the Jew-controlled BBC when Britain is supposed to leave the EU (European Union). This piece on possible Jew-planned WW3 after 'Brexit' is by Hexzane527. Anonymous scripts are read out by Jews (Kuenssberg or Kuennsberg, Adler) and a whore of Jews, Reeta Chakrabarti, who read out a piece a few days ago about the fake 'Holocaust'.

At about this time, BBC 'news' is running a standard fraud, this time on 'coronavirus', supposedly starting in China. It's amusing to see their tenth-rate actors trying to look serious, all with no idea how difficult it is to test for viruses...

Mary Martha Sherwood (born 1775; died 1851, in England) had her History of the Fairchild Family; ... being a collection of stories The importance and effects of a religious education published in 1818, when she was in her early 40s, in book form. She was married into a Church of England family; her accounts were probably taken from life. Two volumes were added, in 1842, and later in 1847, though this latter is reported to have shared authorship. As far as I can tell, she wrote well before copyright law applied to writings; anyway, title pages and illustrations online show a lot of variation. (Charles Dickens, born 1812, died 1870, as a perhaps comparable author).

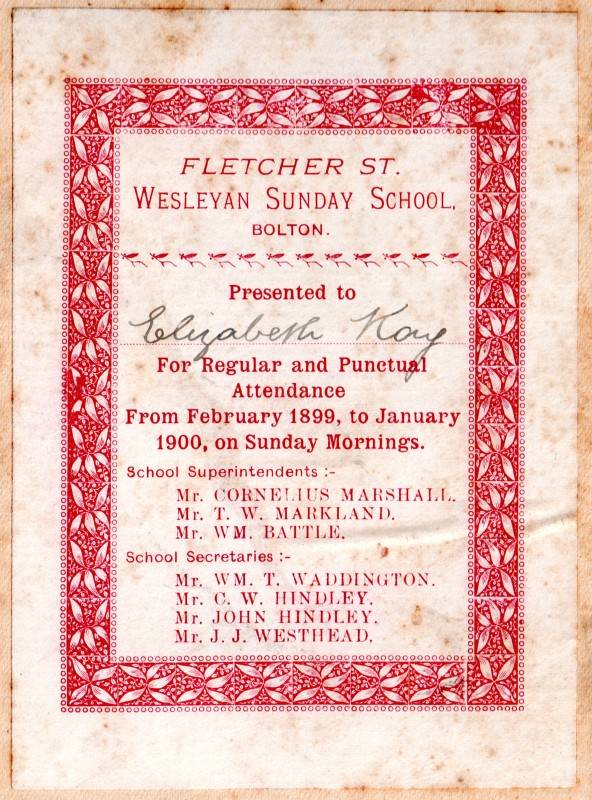

I found a copy of this book, given in 1900 as a Sunday School Prize, Published in London by James Nisbet & Co, Limited, of 21 Berners Street, London. Nisbet published the "Pilgrim" series, and the smaller "Golden Silence" series. (These were not all religious; for example no. 31 of their Pilgrim series was Nor'ard of the Dogger by E J Mather.) The general, undated appearance of my copy suggests it was warehoused for years as a prize.

Sure enough, about a third of the way through the complete 3-volume book (p 147 in my copy) is Story of the Absence of God in which the son Henry tries to learn Latin; his father becomes infuriated, and decrees that the family should ignore Henry. The point is that Latin was needed to become a clergyman. Russell, a member of an aristocratic family, made fun of this ambition, a fashion established by 'Jane Austen'. This was all very well for them, but, as with U.S. Jews now, and people in the BBC and the Civil Service now, a lifetime career was more-or-less guaranteed. Patrick Brontë is a good example of a determined careerist, rewarded with a parsonage in a recently built part of Yorkshire. England was divided into parishes, sufficient of them, with the then death-rate, to guarantee livings to something like half of the entire output of Oxbridge colleges. In my young and naive days, I'd thought many academics and professors wanted to discover and invent and classify things and ideas, but of course this is rare. So Henry's dad might well have been right to try to continue, with his own inside knowledge, his 'career'.

The principle is similar to 'tenure', in what are called 'universities' now, in which evidence of adequate acceptable performance over many years lands the job. In both cases there's something like a commissar class to check.

Russell in Power, his chapter Powers and forms of governments wrote: 'In capitalistic enterprises there is a peculiar duality of purpose: on the one hand they exist to provide goods or services for the public, and on the other hand they aim at providing profits for the shareholders.' There's a similar duality in official religion.

Maybe I missed it, but I've never seen any attempt to assess the costs and benefits of established Christianity. No doubt it was useful to register births, marriages, and deaths, and have some format for stability, and have distributed centres covering an entire country. There were literacy and calendars and holidays. Some vicars made discoveries or creative works; Brewer's Phrase and Fable, Stirling's engine, Cox's orange pippin, twiddly hazel, Tristram Shandy, and (at a higher level) The Compleat Angler, illustrate the sort of thing. Governments must have regarded the Church of England in the way the BBC is regarded, as a convenient source of lies, broadcast across the country, telling people who to hate and fight and celebrate and admire—however much they may have contradicted official dogma. Its constant grasping must have been tolerated.

The weakness of course is the fundamentalist dogma. (Russell liked to point out that the Service for the Ordination of Deacons all the respondents had to agree to: Do you unfeignedly believe all the Canonical Scriptures of the Old and New Testament?)

Since the vast promotional push for the King James translation of the Bible—not just the Jesus part, but the much longer part from the mists of the oriental Mediterranean—and deliberately mistranslated to obscure horrors and atrocities—and since Edward Gibbon on 'antifa'-style funded thugs, and the emergence of novelties such as the early 20th century Scofield Bible (published by Oxford University Press) it's become clear that the Church of England is almost as phoney as the Bank of England.

One of the attractions of the Church of England is or was the administrative structure. A prime Archbishop, approved governmentally from a shortlist; Bishops; a collection of appointees with mysterious titles—what on earth are Deacons, Vicars, Parsons, Curates? (Many people held different livings, and hired Curates to look after them). A 'Grange' had some ecclesiastical function. A tithe barn was for storage. What were Priories, Monasteries, Nunneries?

In about 1900, a road called 'Chapels' in Darwen, Lancs, then a major part of cotton spinning and weaving in Britain, housed Methodists, Primitive Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers, and an Ebenezer chapel. And no doubt others which have vanished.

In about 1970 I looked at a C of E place, the incumbent having servants, who all looked downcast and bullied. He read the Daily Telegraph which even then I knew censored out atrocities in Vietnam. I had an unpleasant insight into the Church in it supposedly great days, a vast landowner doing nothing about wars and violence.

Much of this must be attributed to 'Jews' in collaboration with more or less secret groups of locals. Here's my view on the spread of Christianity and Islam by Jews. South America is under-represented.

Sherwood could be an Americanised form of some Jewish name(s), but in this case she looks English. Her maiden name was Butt. At least one hymn or poem in her book is attributed to Butt.

My collection of books includes THE QUIVER An Illustrated Magazine for SUNDAY AND GENERAL READING. Published in 1872 by Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, London, Paris, and New York. 864 pages with about 53 'etc etc' contributors. Mostly stories with occasional engravings. Note the Jewish publisher. There are incursions of Jewish themes. I wonder if the themes are designed to ensure religious people can act their parts.

Eric Blair ('George Orwell') disliked this book. Oddly, he recognised that punishment can help children learn things they aren't interested in, and states that at school he remembered pupils asking to be hit, to reinforce (or just enforce) their learning of, perhaps, some grammatical point.

Rae West 1 Feb 2020