Selected Reviews by Subject:- Film, TV, DVDs, CDs, media critics | Health, Medical | Jews (Frauds, Freemasons, Religions, Rules, Wars) | Race | Revisionism | Women | Bertrand Russell | Richard Dawkins | Martin Gardner

Teaching Critical Thinking...?

Some books published in Britain 1926-1941. And some outside those dates.

Rae West March 9 2020

I'll put my conclusions, in teaser style, at the end of this piece.

After the First World War, and its stupefying torrent of propaganda, not surprisingly, many people thought they should learn about, and be on their guard against, newspapers, paid-for books, advertisements, political mountebanks, would-be dictators, and so on. Radio was new and brought new challenges, as TV did thirty years later. Huge population shifts between countries increased. H G Wells caught some of this mood, though he failed to counter the propaganda; his Outline of History, and vague ideas about the unity of mankind, were popular. Few people at the time had any idea that substantial portions of mankind were antagonistic to this attitude, and were, for want of a better phrase, aggressively parasitical.

Think-for-yourself books appeared in Britain after the First World War. Many people, including H G Wells, disgusted by the sheep-like behaviour of their fellows, but sympathetic to their essential innocence, naturally thought that self-aware and well-informed people were a good and desirable thing. But there was opposition from aristocrats and military conventionalists and mysterious subtle opponents, at this distance identifiable as international Jews combined with national secret societies, usually 'Freemasons'. These had supremacist ideas of their own, with no intention of enlightening others, and no belief that it might be possible.

These books, as we'll see, combined obsolete logic, etymological considerations, and political and economic arguments taken from the mass media of the day. There was nothing very deep, and nothing much on the ancient views of the world assumed by other peoples. The 'British Empire' added some anthropological detail.

I'm suggesting here that troubled times lead to books of inquiry, but I've excluded Francis Bacon on 'idols of the crowd' and fallacies generally because of difficulties due do the passing of time. And one might expect the times after Cromwell, after Napoleon, and after the United States' civil war/war of the States, to have produced a crop of inquisitive books, but these seem not have appeared on any scale.

In my view, the most important failure was to fail to examine the roots. (A modern (2020) parallel failure is to not examine the roots of virology and testing of the so-called 'coronavirus').

In the USA, after 1918, Americans, thousands of miles from wartime action, and after the 'Fed' had been installed, was at the mercy of Jews. Who, obviously, had no desire to educate Americans into thinking deeply. So in the USA, along with the Jewish media of New York Times and radio and movies and the rest of it, timewasting books multiplied, joking about other people's silly pre-scientific beliefs. Mencken, Jastrow, Stefansson of Adventures in Error, and (later) Bergen Evans and Martin Gardner illustrate the types. Do You Believe It? (Otis W Caldwell & Gerhard E Lundeen, New York, 1934), Shattering Health Superstitions (Morris Fishbein, 1930), Doctors Don't Believe it, Why Should You? (Dr Thomen, New York 1941) were medical equivalents. And of course Jews built up to the Second World War, with large numbers of Jews acting together internationally.

Pre-1914 rationalist books typically dealt with logic or religion. These books don't use much algebraic notation, which of course means they are more likely to be popular, and more like logic in the Sherlock Holmes sense. I've included Jevons' Logic (1876; reprinted at least into the 1930s). There are still people who think that teaching about Aristotle will liberate people into understanding of the world. Religious critics nearly always take the side of some long-established and more-or-less phoney group, particularly when critical of foreigners: the Spanish Inquisition, Roman Catholics, maybe Moslems. There were few critics of Jews: most people knew nothing of the Talmud, or were overawed by money made for example by drugging Chinese with opium or backing wars.

And Post-Second World War books were less concerned with politics: it was taboo to investigate WW2 (for example, mass murders of Germans and Slavs), taboo to look into violence against Jews, taboo to investigate Jewish science frauds such as the myth of nuclear weapons, and taboo to examine USA Jews' support for USSR Jews. In such circumstances, how could anyone write on 'clear thinking'? The ZOG period is probably the worst in the history of whites, even worse than the 19th century history. No wonder squads of 'Sayanim' try to persuade simple whites (such as Kevin MacDonald?), that the 1950s were wonderful.

In the USA, such 'thinking' books as existed tended to be more self-centered, aiming at personal 'growth'.

Note on ‘Jewish’ authors: As far as I've looked, all the inter-war authors listed seem to be Jewish, except for Bertrand Russell, who however was a fellow traveller and/or useful idiot. 'Jews' themselves are coy about this—though considering they think they are chosen by God, this may seem odd. It's a peculiarity of Jews that they can only allow themselves lies about their own history. So it falls to non-Jews to analyse their output.

Virtually all Jews change, or have changed, their names. In the following list, 'Thouless' seems to have been Thewlis; Stebbings seems to be Jewish, and so on.

1878 W S Jevons 'Logic'

1905 E E Constance Jones 'A Primer of Logic'

1910 Alfred Sidgwick 'The Application of Logic'

1926 Graham Wallas 'The Art of Thought' *Long Review!*

1930 Robert Thouless 'Straight and Crooked Thinking'

1936 R. W. Jepson 'Clear Thinking'

1936 A. E. Mander 'Clearer Thinking: Logic for Everyman'

1938 R. W. Jepson 'Teach Yourself to Think'

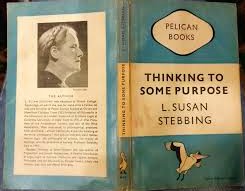

1939 Susan Stebbing 'Thinking to Some Purpose'

1941 Bertrand Russell 'Let the People Think'

1947 Hector Hawton 'The Feast of Unreason'

1967 Edward de Bono 'Lateral Thinking'

1876 and later. W S Jevons 'Logic'

My copy is dated 1922, reprinted unchanged; but it was in print until at least the 1930s.

I'm uncertain if Jevons (economist) was British, but I'll assume so. His book is in numbered paragraphs, 199 in total. He was modern enough to include Venn diagrams. And he included older material, for example phrases from Molière on (in effect) meanings of common words. He included a well-known legal case of the time, the Tichborne Claimant.

He was well-known as a contributor to 'marginal utility theory' (or the 'marginal revolution') in economics. The rather obvious point that people (and animals) do things from their current starting-point, and not from some earlier, later, less developed, more developed, or faraway point. The point was the mathematical phrasing was diagrammable.

Some of his economic material appeared in his look at the Post Office (then rather new) and Telegrams, correcting people who thought that railway companies should charge the same rates as letters.

Jevons has material on science: the causes of rust (water vapour, carbon dioxide, oxygen); rainbows, including by moonlight, and in waterfalls; Newton showing there are two tides in 24¾ hours; sunspots have an eleven year cycle; Newton's rings happen with thin layers; "We know the moon has mountains.. [they] cast longer shadows as the sun is setting, and shorter ones as it is rising."

He included examples from (I suppose) everyday sources, for example on Britons 'never will be slaves' despite magistrates condemning prisoners to penal servitude.

Jevons had a final section on fallacies; fallacies of ambiguity, fallacies of inductive reasoning; that sort of thing.

He does not have sections on abstract thought—property for example, or whether people pursuing freedom individually could make a community. He reminds me of books on ethics: they carefully avoid issues such as opium in China and poverty in Egypt.

1905 E E Constance Jones 'A Primer of Logic'

Written by the Principal of Girton College, Cambridge. This must have been one of the earliest books by a female academic.

Indexed, but only with vocabulary: which is extensive, including medieval Latin terms: Ignoratio Elenchi & Modus Tollens & Petitio Principii & Totum Divisum. And such medieval philosophical historical things as 'Tree of Porphyry' and 'Ramean Tree', after Ramus.

And a wide mixture; here are some— Predicates, J S Mill, Nominalism, Realism, General vs Conceptualist views, Genus, species, Summum, obverse, opposite, opposition, long list of (about 30) fallacies, apprehension, categorematic words, illation, induction by simple enumeration, ostensive reduction, paradox, paralogism, law of parcimony [sic], phenomenon, premisses, sophism, syllogisms, trilemma & polylemma, etc etc [but also signs of Boole's 'Laws of Thought']

A prefatory note thanks J M Keynes, and W E Johnson, for permission to print examination questions in logic; these are pp 160-168. Before these are questions presumably composed by Jones. All are in a scholastic vein.

The book has an unurgent, peak-of-empire style.

The belief that rhetoric and logic together make a complete mind, seems to ignore all the questions of technology and empiricism: as I type (April 25, 2020) official policy is to do with 'Coronavirus'—but almost all the principals clearly have no idea what a 'virus' is, what a test for a virus might do, and how accurate death certificates are. (Plus many other questions). It seems obvious that no amount of rhetoric and formal logic will answer these questions. Here's an online debate with Laura B. who clearly loves logic and rhetoric. If she manages to get the USA education system to teach these subjetcs, I hope she won't be too disappointed with the results.

1910 Alfred Sidgwick 'The Application of Logic'

Sidgwick has sometimes been presented as a distinctly Oxbridge type, formal, stiff, rather dull, and ultimately a failure. This long book regards logic as intended to help 'in distinguishing between good and bad arguments', and 'attempts to state ... the logical doctrine that remain when we discard those parts of the traditional logic which are misleading in application.'

If a reader is in the mood it's fascinating to see what's omitted: nothing much on science or religion or ethics or politics—no need to puzzle over space or physics or biology or wars or rent. There are three main sections: I THE PROGRESS OF DISPUTES, II OBSTACLES AND CROSS PURPOSES, III SOME TECHNICALITIES AND DOCTRINES. It's difficult to see this as anything other than an evasive work, skirting around most issues, including those necessary to deal with the then-opening 20th century. Treating good and bad arguments in syllogisms and other formal structures conceals endless assumptions, guesses, and ideas taken over unexamined.

As a couple of specimens, in 1848 Socialisme by Victor-Prosper Considérant was published (and plagiarised by Marx, Engels, and no doubt others).

In 1879 Henry George's Progress and Poverty (1st edition) was published.

Both were far outside the limits of the books I've mentioned. Whether many people noticed, I don't want to guess. H G Wells bemoaned the educational possibilities running to waste; between the wars there was an analogous process of teaching of errors, attempts at truth, and the inability of most people to learn. And no doubt the years from 1945 have similar, maybe worse, timewasting, lying, fakery and moneyed conventions for some.

1926 Graham Wallas: 'The Art of Thought' *VERY LONG REVIEW!*

Published by Jonathan Cape. Now available free online.

After the previous books, the world had the Jewish coup of the Fed in the USA, and the Jewish coup in Russia. And of course the 'Great War'. Wallas' book is not quite a think-for-yourself book; it's rather more a guide to what to think, something like a literary version of the language and attitudes of BBC radio and films. There had been compulsory education and such things as compulsory drills and conscription and the Bradbury pound. War-time laws remained. I think Wallas invented the expression 'image' in the modern, advertising sense in Human Nature in Politics. However, he claims his book explores how far modern psychology can improve 'the thought-processes of a working thinker.'

Wallas clearly regarded himself as a 'working thinker'. He was one of three men, with Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb—real name probably Jewish—who were wined and dined by Beatrice Potter, later Webb; something like 'the judgment of Paris with the sexes reversed ... Sidney [Webb} who emerged as the counterpart of Aphrodite' according to Bertrand Russell. I'd guess that in fact Beatrice Potter checked them for what could be called Jewish correctness. Wallas therefore had some historical significance.

The London School of Economics dedicated to 'sociological investigation' was founded in 1895, occupying two small hired rooms in John Street, Adelphi. Its move from there to 10 Adelphi Terrace was financed by Mrs Bernard Shaw. [Who, by the way, remains under-researched - RW]. When the University of London was reorganized by Haldane and Sidney Webb in 1899-1900, the London School of Economics was made one of its constituent Colleges, with Webb himself as Professor (unpaid) of Public Administration. The objects of this institution were excellent, but its critics felt that the sociological evidence collected there was to prove the case for a socialism which was not so much defended as assumed. Future graduates and members of its teaching staff were to include Graham Wallas, L. T. Hobhouse, Sir William Beveridge, Clement Attlee, Harold Laski, Hugh Dalton, R. H. Tawney, Kingsley Martin and Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders. ... The Labour Party as we know it is largely the work of their hands. [Note that Parkinson does not check the part played by Jews]

First, note that Wallas may have believed himself to be a Jew; the usual signs obtain, for example odd spelling of his name, suppression of information about his mother, family background mysteriously involving business and money. Another sign is the indifference to war dead of the Great War in Europe; the Jewish attitude was that if Europeans killed each other and Jews profited, that was all to the good. Wallas was a 'working thinker' very careful not to think such thoughts, at least for public consumption.

Wallas has no interest in exposing secrecy and lies, although the highest levels of politics, freemasonry, education, news, the Church of England, armed forces, all had systems of lies which presumably deserved light.

The book has twelve rather long chapters. Let me attempt to summarise Wallas's overview.

The entire book does not discuss ethics: was, for example, the 'Great War' worthwhile? What about events in Russia in 1917 and after? Wallas's assumption is, that men should do what they have been told by the authorities is their duty, and that the State should be obeyed more-or-less unthinkingly. What follows are notes on each chapter. But the book is extraordinarily difficult to review. It has snippets from then-modern psychology, a mixed bag including evolution, but designed to exclude (for example) shell shock, bullying of troops, fear of death, religion, money power, language variations, race, and serious consideration of 'useful education'. It includes, in very concealed ways, Jewish outlooks which Jews assumed without much in the way of critical thought. The chapters don't seem to follow any system, but there may well be a Jewish system with Jews cut out—just as the artist Paul Klee used rough pencil outlines which he partly painted between, and then erased.

An important point—quite difficult to put into words—is the presentation as handed-down, official, and rather unhelpful and 'elitist'. Like 'virtue signalling', but 'education signalling'. There's nothing on selecting the best ways that people, in practice, learn from quickly and easily and permanently.

CHAP I PSYCHOLOGY AND THOUGHT — Wallas wants to bring thought up to the level of technology and science. But one problem is psychologists: some have a 'mechanist' approach, some a 'hormonal' approach. Wallas describes the British Constitution, completely missing violence and war '.. The [British] Constitution has been evolved owing to the need of unifying the social actions of the forty-three million inhabitants of Great Britain. It, like the human nervous system, consists of newer structures superposed upon older, in such a way as to produce both the defect of overlapping, and the compensating advantage of elasticity. The oldest part of our Constitution provides that we shall be governed by our king, whom God has caused to be born.. etc.. almost equally old system, trial by jury. [Joke: note: surely people who rely on idea of professional lawyers have a problem over this institution?] .. On these older parts has been superposed a newer system, which provides that we shall by governed by a Parliament.. On Parliament itself has been superposed a still more recent system, in which the main work of government is done by civil servants and military officers chosen by competitive examination, and by professional judges and magistrates chosen by the ministers but exercising independent authority.'

Not at all helpful.

II CONSCIOUSNESS AND WILL — Quite a lot, not on consciousness, but on 'co-consciousness', 'fore-volition', 'will', and 'autosuggestion'. All taken from common sense, introspection, and so on, without much knowledge of how the brain does its tricks. Then Plato, in Phaedrus, 'half-ironical theory that creative thought was a kind of madness'. Greeks have to be mentioned, of course.

III THOUGHT BEFORE ART — Aristotle, and Hobbes. And thought association. And something like 'lucid dreaming'. Also slang and popular changes: 'the cinema had soaked whole populations in third-rate theatrical conventions..'. The slang expression 'click': '.. spread during the war.. the sound made by the machine when he successful movement was made..'

IV STAGES OF CONTROL — Wallas tries to find a process for the 'working thinker' to use. He finds four stages - Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, and Verification. Well, maybe. Many anecdotes, accounts, tales, poems, mostly of rather unimportant events. For example; 'On June 18, 1917, I passed on an omnibus the fashionable church etc. .. Miss Ashley.. was being gorgeously married, and the omnibus conductor said.. 'Shocking waste of money! But, there, it does create a lot of labour, I admit that.' Perhaps I neglected my duty.. to say.. 'Now make one effort to realize that inconsistency, and you will have prepared yourself to become an economist.'

V THOUGHT AND EMOTION — Starts with a translated extract from a letter by Tchehov. Then a bit of Blake. Then E B Titchener on 'affections', not in the everyday sense. Then Dante's Paradiso, in modern English. Then Wallas on Latin and Greek versification at Shrewsbury School, with 'something of a monopoly of the Cambridge University prizes'. I'm reminded of Bertrand Russell reading Epipsychidion aloud to Alys Pearsall-Smith.

Then we have the sense of humour as a 'sudden glory'. And a Munich journal with caricatures of the Kaiser, and his son 'which every German would now recognize, i.e. after the 'Great War'.

We have about 8 pages on Shelley, officially regarded as emotional; he was booted out of Oxford in 1811 for anti-Christian objections to Christianity. Nobody is discussed as a thoughtful and emotional opponent of Jews. Godwin's Political Justice (1793) has a mention (French Revolution-ish) though post-1945 Godwin gets few mentions, apart from having been married to Mary Wollstonecroft until her death in childbirth. Godwin may, or may not, have been part of the huge obfuscatory movement hiding Jews and Freemasons in France and the USA; Wallas makes no attempt to tackle Godwin, an amusing piece of cowardice since Godwin was one of the very few people who tried to build up a complete new fully thought-out system.

The real point of the chapter may have been to emphasise educated people with revolutionary ideas in the Jewish sense, but not such emotions as wanting ever-more money, or more deaths of other people, or the ambition to be appointed to highly-aid positions without much effort.

VI THOUGHT AND HABIT — Curious chapter entirely concerned with writing: novelists, journalists, daily administrators, and their methods. And ways of rereading, jotting down 'significant fringe-thoughts', waiting for moments of candour from interviewees. But actual thought seems to me not to be considered.

VII EFFORT AND ENERGY — Wallas tries to identify mental energy, by serial quotation, including quotations on relaxation, in case the mental effort are too great. (William James is mentioned, quoted in one of his 'Talks for Teachers' on 'the gospel of relaxation.. preached by Miss Annie Payson Call in her admirable little volume called 'Power through Repose.'). Some sort of creativity theory seems essential to Wallas; I suppose he doesn't like the idea of something predictable, like an architect doing a complicated drawing. Maybe this comes from revelation in the religious sense. '.. Shelley.. wrote to Godwin of the 'alternate tranquillity... which is the attribute and accompaniment of power; and the agony and bloody sweat of intellectual travail.'

Wallas goes on: '.. every thinker.. must be prepared for the sudden necessity of straining effort..'. He quotes Dr E D Adrian on 'The Conception of Mental and Nervous Energy.'

VIII TYPES OF THOUGHT — Longest and what might be the most interesting chapter.

.. No one consciously invented the legal type of thought (with its tendency to treat words as things), or the military, or clerical, or bureaucratic, or academic type; nor need one search for an inventor to explain why the Bradford type of thought is different from the Exeter type, or why a Roumanian peasant thinks differently from a Viennese merchant. On the other hand, a type of thought sometimes follows a pattern that was first created by the conscious effort of a single thinker, Anaxagoras, or Aquinas, or Descartes, or Hegel, and was afterwards spread by teaching and imitation. The prevalence of a type of thought is often due to a combination of.. invention and the .. influence of circumstances. Some one invents a new type of thought, and.. a new fact appears in a .. group environment which makes the new type widely acceptable. .. types of thought.. may be invented and neglected.. and be afterwards enthusiastically adopted in another country.. One can see why Rousseauism.. as interpreted by Jefferson, 'caught on' in America after the Declaration of Independence; or why a crude 'Darwinismus' spread in Germany as the German Empire began to extend beyond Europe; or why.. the Hegelian dialectic fitted the needs of troubled Oxford religious thinkers. The type of thought painfully worked out by Locke and his friends from 1670 to 1690 went to France in 1729 to justify the liberal opposition to Louis XV: Bentham's a priori deduction of social machinery from primitive instinct suited.. the South and Central American colonies after their separation from Spain: Herbert Spencer's Synthetic Philosophy suited Japan after her sudden adoption of western applied science. Sometimes, though with much hesitation, one may ascribe.. spread.. to .. racial features - .. the victory.. of Mohammedanism over Christianity among the stronger African tribes, .. the greater success of Buddhism in the eastern than in the western half of .. Eurasian continent.

More on the French, including H Poincaré

French law, 'a completely logical Civil Code' [really? Wallas gives no evidence]

[William James quoted.. and others.. & tho' Wallas is convinced there are distinctive qualities in the extracts he gives, he doesn't even seem to hint at what he thinks they are.]

WALLAS'S SUMMARY:

Certain ways of using the mind are characteristic of nations, professions and other human groups. Some of these are the unconscious results of environment; others have been consciously invented; and others are due to a combination of invention and environment. The French and English nations have acquired different mental habits and ideals which they indicate respectively by the word 'logic' and the phrase 'muddling through.'

Each habit has advantages and dangers, and it may be hoped that a new habit will some day be developed which will combine both advantages and avoid both dangers. It is less easy to detect an American type of thought. There are indications that a more elastic and effective mental habit may be developing in America than is found elsewhere, but that habit cannot yet be called the national type. The 'pioneer' habit of mind is perhaps more prevalent in America than any other single type; but it seems to be rapidly dissolving under the influence of industrial development, religious change, and the spread of popular interest in psychology. A new standard of intellectual energy may ultimately come to be accepted in America, accompanied by a new moral standard in the conduct of the mind, and a new popular appreciation of the more difficult forms of intellectual effort.]

[Note: national differences between English and others? Starts with rather tedious reminders that not all e.g. English Liberals are the same etc] 174: [Note: English: many variations on the theme of 'muddling through', 'glorious incapacity for clear thought', 'profoundly distrust logic', quoting Canon Barnes, Lord Selborne, Lytton Strachey, Austen Chamberlain - this line of thought attacked by S Stebbing

[French: classic, logical, or mathematical French thinking. Taine & 'the classic spirit', Royer-Collard despising a fact (in contrast with Burke), A Fouillée in 1898 book on French psychology: '.. ours is a logical and combining imagination..' .. French politicians' logic and language 'training'; Voltaire & Montesquieu & effect of French Revolution and 'armed ideas'...]

Writers have invented a Latin race to account for the difference. [Note: stupidly, Wallas assumes without a scrap of evidence that there's truth in these phrases, just because several people have said so. He says Voltaire and Montesquieu seem to imply the opposite; and that 'the Revolution, and the twenty years of 'war against armed ideas' which followed.. fixed.. Reason as the republican ideal in France, and opposition to Reason, in the French sense, as the ideal of the English governing class. ..]

[More on this, but of course sadly anecdotal and impossible to verify.] We can say that the English tradition has produced a greater emphasis on.. Intimation and Illumination, and the French.. greater emphasis on the more-conscious stages of Preparation and Verification.

... in 1917.. we promised equal treatment of Hindoos and Whites in Africa, and.. in 1923, .. we refused.. to carry out our promise in the Crown Colony of Kenya, may prove .. serious.. in the future relations of Great Britain and India. ..'

Treaty of Versailles; differences with French? Catholic calculations about keeping people down

[Belloc and I suppose 'agrarian distributists' - Aristophanes on farmers' fear of Socrates; South Africa followers of Hertzog; 'Green International', peasants of Central Europe; American pioneers and wheat pit, and dislike of 'highbrows'; Wallas of course can't define what an intellectual is... (I think the point of this is Wallas trying to be optimistic about USA)

IX DISSOCIATION OF CONSCIOUSNESS — [WALLAS'S SUMMARY:] The history of the art of thought has been greatly influenced by the invention of methods of producing the phenomena of 'dissociated consciousness.' The simplest and most ancient of these are the methods of producing a hypnotic trance by the monotonous repetition of nervous stimuli. Such methods have important and sometimes beneficial effects on the functions of the lower nervous system; and a slight degree of dissociation may assist some of the higher thought processes; but the evidence seems to indicate that: the best intellectual and artistic work is not done in a condition of serious dissociation. Dissociation, however, often produces intense intellectual conviction; and the future of religion and philosophy, in both the West and the East, depends largely on the conditions under which that conviction is accepted as valid. In Western Christianity, methods of 'meditation' have been invented, especially by Saint Ignatius, which are intended to avoid the dangers of mere dissociation; but the process of direction of the association trains of ideas and emotions by an effort of will is so difficult that it constantly results in the production of the same state of dissociation as that produced by the earlier and more direct expedient of self hypnotism. And, since dissociation remains the most effective means of producing intellectual conviction by an act of will, those who now desire to practise the 'will to believe,' are still thrown back on the old problem of the validity of conviction produced by dissociative methods.]

This entire chapter is aimed against Christianity, of course a mark of Jewish 'thought'. 'Mysticism', and such things as Meditation, retreats, the Church of England, Anglo-Catholicism, hypnotism, alcohol, are assumed to be the causes for such belief. The obvious alternative—that ideas are repeated from childhood, with no alternative—is too much like Judaism, which one seemed to think is the 'rational religion'.

The final three chapters together look at the practical world aimed at by Wallas's 'working thinkers'; essentially, of post-Great War Jewish-directed 'socialised' thought. Or at least that's what I think; naturally, Wallas is not straightforward.

X THE THINKER AT SCHOOL — [SUMMARY:] 'The discipline of the art of thought should begin at an age when the choice of intellectual methods must be mainly made, not by the student, but by teachers and administrators. If Plato were born in London or New York, how could we help him to become a thinker? He would be a self active organism, living and growing in an environment far less stimulating than that of ancient Athens, and unable to discover for himself the best ways of using his mind. His education should involve a compromise between his powers as a child and his needs as a future adult; he should acquire steadily increasing experience of mental effort and fatigue, and of the energy which results from the right kind of effort; he will need periodical leisure, with its opportunities and dangers. ...'

Fascinatingly inconclusive chapter. Wallas doesn't know what to do with Plato—or I think how to pick out promising children. He says that 'present experimental schools in which students are left to acquire thought methods by their own 'trial and error' have not always been successful.' He doesn't think much of British and American education; but of course criticism is easy. Experiments include Prof McMurry, Daltonism, Garyism, the Project Method, the science method of Professor H. Armstrong, Oundle by Sanderson, Abraham Flexner's in 1918, and Middleton Murry's on style, with more anecdotes on style, including extracts which Wallas presents like a proud father showing pupils finding things to say. Wallas falls back on hopes 'that a knowledge of the outlines of the psychology of thought may become a recognized part of the school and college curriculum; experimental evidence already exists as to the effect of such knowledge in improving the mental technique of a student.' The impression left is of continual floundering. And also of continual evasion provided public money continues.

XI PUBLIC EDUCATION — [SUMMARY. Wallas was part of the movement into state education, and part of the enforcement process. He is thoughtful about 'supernormal' pupils; or at least seems to be—he wants a superior caste, like Plato, and like Jews, but is a bit vague as to what superior qualities they should have:] 'In the case of four fifths of the inhabitants of a modern industrial community, inventions of educational method will only increase the output of thought, in so far as they are actually brought to bear on the potential thinker by the administrative machinery of public education. That machinery is everywhere new, and was originally based on an over simple conception of the problem. In England, we are slowly realizing the necessity, (a) of making more complex provision for the 'average' student, and (b) of providing special treatment for the subnormal or supernormal student. Differential public education for the supernormal working class child had to wait for the invention of a technique of mental diagnosis, and only began in England at the end of the nineteenth century; the system is still insufficiently developed, and there is a serious danger that an extension of the age of compulsion in its present form may lessen the productivity of the most supernormal minds. If this danger is to be avoided, we must reconsider our present compulsory system, with a presumption in favour of liberty and variety; American experience shows the intellectual disadvantages involved in the compulsory enforcement of anything like a uniform system of secondary education.'

Laws had to be made to remedy defects of earlier laws, mostly in this case simple assumptions about children, according to Wallas. 1861 'Payment by Results' was followed by 1870 legislation which supposedly isn't just '3 R's'.

Note the assumption that working class kids are all about the same: '.. reading the Parliamentary debates on the English Education Acts of 1870 and 1876, I do not remember.. any sign that any M.P. then realized that the innate or acquired individual differences among.. working-class children .. constituted an administrative problem. .. first recognized .. in the case of extreme mental and physical subnormality. .. 1870.. blind.. deaf.. deficient mentally.. 18902 'special schools' .. 1899 .. power to deal systematically with the problem. .. in 1894 I found that most.. still thought of 'feeble-mindedness' as a temporary condition which could be easily detected by non-specialist observers..'

[Ability and acquirement? Footnote on 'a few of the old endowed 'public schools' in the last third of the 19th century' 'tending to base their competitions for.. upper-class boys rather on innate ability than on acquired knowledge.' Wallas gives Winchester College as an example from his own experience; though without any evidence] and [Other examples, including L.C.C. [London County Council; now non-existent] Junior Scholarships which '.. closely resembled the problems.. in the upper grades of the Binet-Simon tests.', and Galton in 1883. Wallas notes that IQ tests in the US Army in presumably 1917 gave the idea a boost. He says this with no comment on war dead.]

[In Who's Who, at least 5/6 of the highest work.. by the small minority of the population who do not pass through the elementary schools..'

'.. English working-class home.. few books.. too crowded.. severe manual labour.. too tired.. [both Scottish and Jewish working-class homes have more books, Wallas says ... in a middle-class home, unusual ability .. is certain [sic] to be detected by the parents..']

Pages 266-268 on the politics of school-leaving age. Liberal, Conservative and Labour policies and debates are all vaguely glanced at, Labour treated as equal, and of course financial interests, including the parents' and children's. BUT note absence of information on borrowing by the state; I think this shows that the influence of Jewish paper money in the US was working in Britain, though of course unstated and hidden. There was constant upward pressure on school leaving ages.

Wallas gives rather contrived lists of people (Milton, Nelson, Napoleon, Hamilton, Bentham, Sidney, .. Ellen Terry, Mozart, Beethoven) already accomplishing things at the age to which compulsory education is suggested. One such list includes Einstein. None includes Lenin, who spent time in Britain.

[Note: Wallas's own life: slow effect of legal compulsion and violence; effect on working class after thirty years. Also footnote on discrimination in favour of wealthier classes:]

.. machinery set up in 1870 and 1876.. intended to break down the immemorial habit among the poorer working families of either sending the children out to work as soon as they could earn, or keeping them.. intermittently at home to help in the housework or in some domestic industry. In the country villages, where compulsion was often directed by bodies a majority of whom were well-to-do farmers, who wanted.. child labour.., the law was often at first ineffective. In the northern manufacturing towns a 'half-time' system was allowed which dovetailed a gradually increasing measure of compulsion into .. factory regulations. In London .. where compulsion was directed by keen [note: meaning of word:] educationists on the School Board, the law was drastically enforced. I myself took part.. From 1889 .. until.. 1894 I used, as a 'school manager,' to hold a sort of local court in which I decided, with official advice, what working-class parents.. should be recommended for prosecution for the non-attendance, or irregular attendance, of their children, and therefore.. practically what parents in my district should be fined, and, in cases of default, imprisoned.

... I myself believed that almost any hardship was better than that a child should grow up without education. But I am now surprised when I remember how severe was the system.. In some cases I recommended the prosecution of a working widow with young children for keeping the eldest daughter at home; although I knew that the result might be to send the whole family to the workhouse. The system bore with equal severity on the children themselves; occasional truancy was dealt with by corporal punishment at school, and, since the reputation of an English elementary head teacher then depended largely on the percentage of attendance made by children on his roll, some head masters and head mistresses were known to force up their percentages by continual caning. Boys guilty of inveterate truancy were sentenced by the magistrate, at the request of the School Board, either to long terms of imprisonment in 'Industrial Schools,' or to short terms in penal 'Truant Schools.' On his second appearance at such a Truant School a boy received, as a matter of routine, a heavy flogging. It was only at the end of the nineteenth century, when, after thirty years of compulsion, the habit of school attendance had been created in the working-class districts of London, that the London Truant Schools were closed, and the severity of the whole system was diminished. But meanwhile the perpetual presence of young rebels.. made the preservation of mass-discipline in large classes the supreme duty of every elementary teacher, and that fact reacted disastrously on the intellectual atmosphere of the school.'

Footnote says 'compulsion of such severity would have been politically impossible if it had been applied to the more articulate middle classes; but the school attendance officers in London were told not to visit houses whose annual rental, judging from the outside, was £40 or over..']

XII TEACHING AND DOING — [SUMMARY: Note: he seems to want 'a small minority of future professional thinkers'; I'd guess he was thinking of Jews, or possibly something like nonconformists; he's vague. But I interpret this final chapter as a tantalising plea, like an advert for a national lottery, offering prizes but not complete honesty:] 'The proposal to raise the age of educational compulsion is often combined, in England, with a scheme to make teaching, like law and medicine, a close 'self governing' profession, with a monopoly of public service. That scheme involves serious dangers to the intellectual life of the community, and especially to the training of potential thinkers; it ignores not only the possible opposition of interest between the consumers and the producers of education, but also the 'demarcation' problem between the producers of education and the producers of thought. This over simplification of the problem is partly due to the fact that those engaged in the more general forms of intellectual production are not organized, and do not claim, as other professions claim, a part in the training for their profession. Experience shows that the teaching of any function is sterilized if it is separated from 'doing'; but are the English speaking democracies prepared to offer special and expensive educational opportunities to a small minority of future professional thinkers? Perhaps some local authority might be induced (if legislation closing the teaching profession did not, meanwhile, make it impossible) to start an experimental school for students from all social classes who belong to the highest one per cent. in respect of intellectual supernormality, and who ask to be prepared for a career of professed thought. The staff of such a school would be so chosen as to keep in touch with intellectual work outside the school; the students would be encouraged both to develop their own individual talents, and to realize the social significance of their work; and the success of the school might influence the development of a new intellectual standard in other schools. But such an expenditure of public funds would run counter both to professional interests and to many of the traditions of democratic equality, and it may have to wait for a widespread change in popular world outlook.'

'.. the whole history of professional organization since the 'guild' system of the late Middle Ages shows that if a monopoly of service is given to the persons on the register of any profession, and the right to admit and to remove from that register is given to a body consisting of representatives elected by the profession, the right of registration will be primarily used to secure the interests of the existing members of the profession, as producers, against the rest of the community, the living and still to be born, as consumers. In drawing up, for instance, conditions of admission, the desire to raise salaries by restricting numbers will always..' [Yes, yes!! Thank you professor. Thank you. But do you have evidence?]

[Footnote on NUT, National Union of Teachers, in 1925; NUT has 'done more than any other body to destroy the intolerable social atmosphere which resulted from' the power of the old English 'governing class'.]

'.. listening to a memorandum on Training Colleges 'as recently as 1842' on the formation of character of the schoolmaster, modest respectability, humility.. gentleness.. performance of those parochial duties..'; this is in reference to the 'intolerable social atmosphere which resulted from' the power of the old English 'governing class.'

FULL INDEX of Wallas, The Art of Thought

[I know this is long. Of some interest to show 'education signalling' in action].

Accidia, 221, 222

Adams, Sir John: Child Psychology, 250

Adonis, cult of, 221

Adrian, Dr. E. D., 44n, 169

Æschylus, 28, 91, 167

Agassiz, Louis, 234

Alaric, 219

Albert, Prince Consort, 233, 287

Alekhin, 72 [chess-player]

Alexander of Macedon, 232

[American education; Wallas makes a number of asides on this, though they all seem to be taken from official boards or more-or-less official authors]

Anaxagoras, 171

Aquinas, St. Thomas, 171, 215

Archimedes, 43, 233

Aristophanes, 104, 198, 307

Aristotle, 27, 63, 131, 232, 260, 306

De Memoria, 62

Ethics, 155, 167, 212

Poetics, 121

Armstrong, Prof. H., 245

Arnold, Thomas, 241

Ashley, Miss, 85

Atkinson, G. T., 247

Aubrey, John, 95

Austin, John, 24

Autocrat of the Breakfast Table (Holmes), 164

Averroes, 307

Bacon, Francis, 84

Baird Smith, Colonel, 160

Balfour, Francis, 158

Ballantyne, James, 144

Barnes, Canon: The Problem of Religious Education, 174

Barrie, J. M.: Sentimental Tommy, 297n

Baudelaire, 121

Baudouin: Autosuggestion, 53n, 206, 224

Beethoven, 210, 268

Belloc, Hilaire, 199

Bentham, 166, 172, 199, 268, 302

Bernhardt, Sarah, 268

Berthier, Father, 217

Beveridge, Sir William, 137n

Binet, 237, 262

Bird, Grace E., 234n

Blake, William, 108, 122, 208

Bland, Hubert, 299

Boutmy, E.: Psychologie politique du peuple anglais, 175

Boutroux, E., 77

Boyer, James, 299

Brooks, Van Wyck: Ordeal of Mark Twain, 196

Bruce, H. A.: Psychology and Parenthood, 80n, 105n

Bryan, W. J., 116, 190, 201, 202

Buddhism, 172

Burke, Edmund, 175

Burt, Dr. Cyril, 293, 295

Butcher, J. G.: Translation of Poetics, 131n

Call, Annie Payson, 170; Power Through Repose, 162

Campbell, Mrs. Olwen, 127n; Shelley and the Unromantics, 126n, 159n

Campbell Bannerman, Sir Henry, 178

Canterbury, Archbishop of, 147

Carlyle, Thomas, 92, 307; Latter Day Pamphlets, 115

Carpenter, Edward, 210

Carrel, A., 89, 143

Carroll, Lewis: Alice in Wonderland, 70

Cassian, 219, 223; Institutes, 216, 221n

Castlereagh, 302

Cattell, Professor, 262

Catullus, 111

Chabanei, Paul: Le Subconscient chez les Artistes, 105n

Chamberlain, Austen, 174, 184, 186

Chapman, Dom John, 220, 224

Chapman, George: Transition of Homer, 91

Chesterton, G.K., 118, 201

Churchill, Winston: World Crisis, 117

Clemenceau, Georges, 178

Clifford, W. K., 117

Cockburn, Sir Henry: Memorials, 252n

Coleridge, S. T., 152, 207, 298

Columbia University, 142

Comité des Forges, 184

Communists, Marxian, 33

Copernican astronomy, 115

Coplestone, Edward, 126

Coss, Prof. J. J., 142

Coué, Emile, 206

Crane, Dr. Frank, 189, 192, 194, 200

Curran, John H., 208

Curzon, Lord, 187

Daltonism, 245

Dante, 159, 199, 210

Darwin, 27, 87, 141, 172, 182, 199, 251; Origin of Species, 124

Davy, Sir Humphry, 28

Descartes, 28, 148, 171, 199, 228, 251

Dewey, John: How we Think, 98, 164

Dickens, Charles, 135, 145

Dionysus, theatre of, 198

Donne, John, 58

Dowden, Edward: Life of Shelley, 163n

Drew, Mrs. Mary: Catherine Gladstone, 93

Drinkwater, John, 153, 195; Loyalties, 101; Olton Pools, 123

Ebbinghaus, 262

Eddington, Prof. A. S.:

Space, Time and Gravitation, 57

Einstein, 199, 260, 285

Eliot, Dr. Charles W., 241; A Late Harvest, 240

Eliot, George, 154, 285, 302

Erskine, 144

Faber, Father, 223; Spiritual Conferences, 221

Faraday, Michael, 28, 182

Fielding, Henry, 182

Finlayson, James, 251

Flexner, Abraham, 246

Forster, E. M, A Passage to India, 118

Forster, John: Life of Dickens, 135n, 145

Fouillée, A., 178; Psychologie du peuple français, 175

Frazer, Sir James: Golden Bough, 221n

Freud, Sigmund, 70, 77, 249; Interpretation of dreams, 74

Froebel, F. W., 233, 234, 236

Fry, Roger: The Artist and Psychoanalysis, 210n

Fundamentalists, 191

Galileo, 115

Galton, Francis: Enquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, 262

Garnett, Constance, 108

Garnett, Dr. William, 261

Gary Schools, 246

Germanus, 216

Ghiberti, 28

Gibbon, Edward, 92

Gilgamish Epic, 190

Gilkes, A. H,, 289

Gladstone, Mrs., Life, 92

Gladstone, W. E., 92, 178

Godwin, William, 127, 128, 162; Political Justice, 126

Goethe, 90, 228, 291

Gokhale, 303

de Goncourt, R., 80n

Gorky, Maxim, 111

Graves, Robert, 71

Haldane, Prof. J. S., 39n; Mechanism, Life and Personality, and The New Physiology, 57

Hamilton, Alexander, 28, 234, 268

Hammond, J. L. and B., 42n

Harcourt, Sir William, 158n

Hare, J. H. M., 242, 302

Hartley, David, 32

Harvard, President of, I37

Harvey, William, 182

Hazlitt, Henry: Thinking as a Science, 105, 139, 153

Head, Dr. Henry, 36, 40, 58

Hegel, G. W. F., 24, 171, 172

Helmholtz, Hermann von, 79, 80, 89, 93, 96, 141, 241

Hertzog, General, 199

Heuristic Method, 245

Hitchener, Elizabeth, 126, 127

Hobbes, Thomas, 63, 69, 65, 141; Leviathan, 62, 83, 95, 115

Hobson, S. G.: National Guilds, 288n

Holbein, Hans, 274

Homer, 92

Horace, 92, 112

Housman, A. E., 159, 160

Howley, Prof. J., 217, 224; Psychology and Mystical Experience, 215

Hughes, William, 199

d'Hulst, Mgr., 221n; The Way of the Heart, 222n

Hume, David, 32, 64n

Hunt, Leigh, 298

Huxley, Julian: Essays of a Biologist, 56

Huxley, T. H., 84, 147, 182; Science, Art, and Education, 85n

Ignatian Meditation, 225

Ignatius Loyola, Saint, 217, 227

Independence, Declaration of, 172

Industrial Revolution, 132

d'Indy, Vincent, 104

Inge, Dean, 211

Ingpen, 128n; Letters of P. B. Shelley, 127n

Isaac, Abbot, 216

Jackson, Andrew, 188

James, Henry, 144, 195

James, William, 77, 159, 162, 186, 187, 201, 214, 228, 285; Principles, 95n, 96, 122, 151n, 165; Selected Papers on Philosophy, 160n, 165, 202n; Varieties of Religious Experiences, [sic] 212, 213

Jastrow: The Subconscious, 90

Jefferson, Thomas, 172, 188

Jesuits, 226

Joan of Arc, 209

Jonson, Ben, 28

Kaiser, the, 116

Kameneff, 187

Keats, 91, 302

Kelvin, Lord, 228, 285, 302

Kennedy, Dr., 247

Kepler, 233

Keynes, J. Maynard, 291; Economic Consequences of the Peace, 132

Kitchener, Lord, 137

Kitson, H. D., 240, 246

How to Use your Mind, 239, 250n

Koffka, K.: The Growth of Mind, 31

Köhler: The Mentality of Apes, 31, 230

Kreisler, Fritz, 239

Külpe, 109

Lachapelle, G., 181

Lamb, Charles, 297, 298

Lashley, K. S., 43

Law, English and French, 182

League of Nations, 115; Assembly of, 184

Leibnitz, G. W., 28

Lenin, 24, 45

Leuba: The Psychology of Religious Mysticism, 222

Lewis, Sinclair, 189; Babbitt, 192

Liebig, Baron Justus v., 26, 33; Organic Chemistry, 29

Lippmann, Walter, 138

Lloyd, Charles, 298

Locarno, Pact, 23

Locke, John, 57, 64n, 172, 199; Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 64

Loeb, J., 38n, 39n, 57

Louis XV, 172

Lusk, Senator, 199

Lutherans, 213

Lyttelton, Lord, 93

Macaulay, Lord, 92

MacCurdy, J. T., 32, 39n; Problems in Dynamic Psychology, 32

MacDonald, J. Ramsay, 307

MacDougall, W., 34, 39n; Outline of Psychology, 32, 38n, 42n; Social Psychology, 48

McKim, Charles, 195

McLoughlin, 239, 240

McMurry, Prof. F. M.: How to Study, 98, 245

Madison, James, 28

Manning, Cardinal, 88

Marlowe, Christopher, 28

Marx, Karl, 39n; Das Kapital, 35

Masaccio, 28

Masefield, John, 160

Maudsley, H.: The Physiology of Mind, 162

Maxwell, James Clerk, 158

Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art (New York), 195

Mill, John Stuart, 153, 154; Autobiography, 155n

Milton, John, 111, 153, 268, 302; Paradise Lost, 150

Mohammedanism, 172

Montaigne, 105, 182

Montesquieu: Esprit des Lois, 177

Morgan, Prof. Lloyd, 166

Morris, William, 156, 242

Mozart, 151, 210, 268

Mumford, E. P., 41n

Murry, J. Middleton, 159; Problem of style, 100, 111, 121n, 151, 158, 251

Mussolini, 24, 46, 187

Myers, Prof. C. S., 35, 39n, 169

Napoleon, 235

Napoleonic War, 130

[Note: influence of media: Natural behaviour of people; there's a remark somewhere on how one can watch drink and jealousy produce their natural effects, in East London - or at least could, before the cinema spread new artificial conventions of behaviour]

Nelson, 268

Neoplatonist, mysticism, 205

Nettleship, Richard Lewis, 248

Nevinson, H. W.: Changes and Chances, 289n

New Republic, 233, 240, 241, 278

Nicholson, William: New Review, 116

Nunn, T. P., 38n, 3gn; Education, its Data and First Principles, 38

O'Leary, De Lacy: Archaic Thought and its Place in History, 215n

O'Neill, Eugene, 200

Oundle, school, 302

Oxford International Psychological Congress, 35, 58n, 169, 215

Page, W. H., 186, 187, 291; Life, 202

Painlevé, Paul, 184

Palacios, Prof. Asin: Escatologia Musselmana, 215

Palmerston, Lord, 174, 178, 183

Paul, Abbot, 222

Paul, Saint, 205, 307

Peacock, Thomas Love, 128

Petrarch, 113

Phidias, 210

Pilgrim's Progress, 164

Pillsbury, W. B., 54; The Fundamentals of Psychology, 29

Plato, 28, 91, 121, 129, 199, 210, 228, 230, 231, 232, 233, 291, 306; Phaedrus, 55, 56, 128, 209; Republic, 55; Symposium, 80n, 128; Timaeus, 209

Plebs League, 48; Outline of Psychology, 33

Poincaré, Henri, 76, 77, 80, 81, 93, 96, 180, 181; Science and Method, 75, 80, 94

Poincaré, Raymond, 183, 187

Prescott, Prof. F. C.: The Poetic Mind, 56n, 120

Project Method, 245

[Public schools, anecdotes: 241-2, 247-8, 289]

Rabelais, 182

Reform Club, 26

Rembrandt, 210

Richardson, Leon B., 277

Rignano, E.: The Psychology of Reasoning, 80n, 162n, 175n

Rivera, 24

Rockefeller Institute, 143

Roman law, 27

Roscoe, F., 280

Rousseau, 233

Rousseauism, 172

Royer Collard, P. P., 175

Salisbury, Lord, 178

Sanderson, of Oundle, 245

Santayana, G., 188n

Schiller, 105

Schopenhauer, Arthur: Parerga und Paralipomena, 91

Scott, Sir Walter, 144

Selborne, Lord, 174

Shaftesbury, Lord, 42, 68n

Shakespeare, 28, 102, 123

Shand, A. F., 160

Shaw, Bernard, 156, 164, 201, 285, 299; John Bull's Other Island, 193

Shelley, 91, 125, 126, 128, 162, 241, 285; Defence of Poetry, 128, 130, 131, 132; Philosophical View of Reform, 130

Sherrington, Sir Charles, 32, 44n

Shrewsbury School, 111

Shuttleworth, J. K., 283n

Sidgwick, Henry: A Memoir, 157, 158n

Siddons, Mrs., 268

Sidney, Sir Philip, 268

Simonides, 160

Simplicissimus, 116

Smith, Logan Pearsall, 117, 125

Socrates, 28, 104, 167, 198, 209, 230, 306, 307

Sophocles, 28, 239

Spencer, Herbert, 153, 155, 162; Autobiography, 154n; Synthetic Philosophy, 172

Spencer, Lord, 178

Spender, J. A.: Life of Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, 178n

Spinoza, Baruch, 199, 234

Stamp, Sir Josiah, 291; Studies in Current Problems in Finance and Government, 305n

Stephens, James, 102

Stone, C. W., 250

Story, William Wetmore, 195

Strachey, Lytton, 116, 177; Queen Victoria, 174

Sufist, mysticism, 205

Swinburne, Algernon, 151

Taine, H., 175

Tasso, 128

Tawney, R. H., 268, 275, 276; Secondary Education for All, 266, 279

Tchehov, Anton, 111; Letters, 108

Teachers' Registration Council, 279 seq.

Teresa, Saint, 213

Terry, Ellen, 268

Theosophist, mysticism, 205

Thirty Years War, 181

Thouless, Dr. R. H., 214

Titchener, E. B.: Experimental Psychology of the Thought Processes, 98n; Feeling and Attention, 109

Trevelyan, C. P., 267

Trevelyan, Sir G. O.: Life of Macaulay, 92n

Trollope, Anthony, 88; Autobiography, 92

Tsai, Dr., 124

Tufnell, E. C., 283n

Twain, Mark, 196, 197

Vandals, 219

Vardon, Harry, 48, 100; How to Play Golf, 46

Varendonck, Dr. J.: Day Dreams, 66 77, 85, 97, 101, 104, 135, 136, 140, 210n; Evolution of the Conscious Faculties, 73, 75n

Velasquez, 210

Versailles, Treaty of, 23, 132, 183, 184

Victoria, Queen, 116

Vinci, Leonardo da, 291

Vischer, 105

Voltaire, 92; Letters on the English, 177

Wace, Dean of Canterbury, 147

Wace and Schaff: Select Library of Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, 216n

Wallace, A. R., 87

Wallas, Graham: Human Nature in Politics, 121n; Our Social Heritage, 83n, 249n, 282n; The Great Society, 95n

Warren, Prof. Howard C.: History of the Association Psychology, [sic] 62n, 64n

Watson, Dr. J. B., 38n, 43, 57, 58

Webb, S. and B., 282

Webb, Sidney, 261, 239

Wells, H. G., 201, 246, 300; Outline of History, 190

Whitman, Walt, 196

Woodworth, R. S.: Dynamic Psychology, 37n

Wordsworth, 90, 152, 159, 160

Wundt: Grundzüge der Physiologischen Psychologie, 98

Yale Review, 138

Young, Edward: Conjectures on Original Composition, 124

1930 Robert Thouless: 'Straight and Crooked Thinking'

First published in 1930. I don't have a full publishing history, but certainly it was reprinted to at least 1967. Thouless was a psychologist, I think academic, i.e. not having to work with patients. His The Control of the Mind was I think published in 1932. That title seems to suggest control over the minds of others, but is more like self-control, with the object of getting something you want.

I think Thouless mainly copied and rewrote old stuff, although some books after Thouless acknowledge him in glowing terms.

The logical part has 38 fallacies which Thouless identified, or copied—there are almost this same number in Jones's 1905 book, A Primer of Logic, and on page 170 of my paperback he talks about text-books of logic and their lists of 'fallacies', where he claims his list is 'something quite different. Its aim is practical and not theoretical.'

The next parts of Thouless are, first, his philosophy—rather a ragbag, not very deep, a sort of British empiricism, as indeed the arbitrary number of 38 suggests], and second, his psychology—his main concepts are suggestibility and prejudice.

His topics include the press—Kingsley Martin, The Press The Public Wants is mentioned; education; nationalism and national stereotypes; the First World War; Nautical metaphors, taken from A.P. Herbert's What a Word!; Julian Huxley's letter in The Times on their names of rivals in the Spanish Civil War; and Germany as seen by England. Other books he mentions include Prof Charlton, The Art of Literary Study, Bentham, Theory of Fictions, Plato's Republic. Other topics include Aristotle's BARBARA mnemonic, Charles Darwin's note-making habits, Hobbes, and Kropotkin, for their views on human nature, telepathy, the fallacy of the beard, and life after death.

There's a mock conversation at the end of the book, in which three men, a business man, a professor, and a clergyman, discuss socialism and a general election and assorted controversial subjects; Thouless put in as many crooked arguments as he can. Or at least, that's what he claimed—in fact all the arguments are newspaper-based. There are no personal beliefs or anecdotes, which may introduce unofficial views. There are no illustrations of research or burrowing below the surface.

The book is quite convincingly written; it's only on further thought, or on trying to put Thouless into practice, that the limitations start to surface. A book reprinted after forty years of enormous change must be suspected of serious omissions. In my view, the outstanding defect is the failure to identify evidence and its sources, if these indeed exist. Thouless in his later versions says nothing on Nuremburg Trials, or concentration camps, or what happened to the British Empire, or Eisenhower and deaths by the Rhine; just as he said nothing about the 'Great War', within living memory, most of which was shrouded in almost total secrecy. He says nothing on mysterious events in the recent war, and whether anything can be said about them. Thouless says nothing on money, what it is, and what can be done with it. Scientific issues are of course not touched: how many people can discuss electricity supplies, or war deaths, or the real causes of the supposed 'Spanish flu' epidemic of the time, or events in the USSR?

As with almost all books, there's no way to tell how much material might have been censored or cut out.

1936 R. W. Jepson: 'Clear Thinking - An Elementary Course of Preparation for Citizenship'

Rowland Walter Jepson, M.A.—M.A. was an honorary award by Oxbridge, issued automatically a year after a B.A.; other British universities offer only a B.A.!—I think—1888-1954. Formerly Headmaster, The Mercers' School, Holborn, London. Before the vast growth in universities, many text-books were written by schoolmasters. And many were very good: H S Hall & S R Knight's Elementary Algebra (1st edition 1885) and E J Holmyard's Inorganic Chemistry (1st edition 1922?) illustrate the type. A modern utterly worthless type is Blair Unbound by Anthony Seldon, apparently a headmaster with 25 titles more-or-less by his team.

Clear Thinking was first published Feb 1936; the author being about 50. The introduction says it was the result of an experiment with Lower Sixth Form boys. The title was partly borrowed: 'Training for Citizenship.' The fifth edition, 1954, was published a few months posthumously. It included a new chapter on Propaganda 'and an additional Appendix ... on "Reading the Newspaper"'. Perhaps luckily, it pre-dated television; I wonder what Jepson would have made of TV. I don't think radio is mentioned; the book is unindexed, and seems written-language based, largely of course modern English.

Clear Thinking is saturated with the values of English public schools of the time. For example, it includes Greek and Latin; it has an interest in citizenship as activity, not just passive absorption of handed-down memes; topics are always expanded formally; its introduction lists influences and sources; there are topics for further discussion, problems, examination questions. The rather pompous appearance must have limited its sales; I'd guess Jepson's slightly later book Teach Yourself to Think of 1938 was cut down and simplified by the firm editorial hand of The English Universities Press Ltd.

Jepson may have had Jewish connections; I haven't made much attempt to check, but the Avotaynu surname index lists JEPPESEN. For people ignorant of Jews, this is important when anything about Jews is considered. Jewish-written books are dangerously partisan. People without interest in Jews need to 'wise up'; they are vastly important, and hugely damaging. Just as one tint example: David Dimbleby 'worked' his whole life at the BBC, only being revealed, more or less accidentally, as a Jew late in life. He was the principal face of the TV Question Time programme. For much of this time the was no public method to even record these broadcasts. Here's my own chronology of Jews if you need an introduction.

I recommend that thoughtful critics try to cast their minds back to 1936. What subjects cried out for clear thought from citizens who wanted to learn? Here's a list of eight, taken at random:

• (1) Should the 'Great War' (First World War) be investigated, to try to work out what effects it had?

• (2) Looking at the Church of England, how big a landowner was it, and did it use its wealth usefully?

• (3) Were atrocity stories in the so-called 'Soviet Union' true?

• (4) What happened in Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, the Polish Corridor, and other geographical oddities?

• (5) What exactly is money?

• (6) Who owns newspapers, and the BBC, and how much influence do owners have? Can they publish what they want?

• (7) Can you say anything about the costs of war and the results of war?

• (8) How useful is party politics in carrying out people's wishes?

Just my list; by all means make your own. We'll leave that for the moment, and browse through Jepson.

The book has 9 chapters, plus 5 miscellaneous sections. There are three chapters on psychology—thoughts, memory, words. Two chapters on errors and bias. Three chapters on (roughly) philosophy—observation, memory, induction, deduction. And a chapter on fallacies.

It's not easy to pin down and expose thinking. The layout involves something like (his capitals):

INDUCTION and GENERALISATION [investigation may be needed; his examples include eventual success of clever or dunce children; whether red-haired people are short tempered; cause and effect, simplification, coincidence, analogies. Mostly English examples.

DEDUCTION [Venn diagrams, syllogisms, 'drawing the line', False dilemma, 'false logic']

COMMON FALLACIES [Composition and division, parts and whole; fallacies of accident, where changes in circumstance are ignored (or of course unknown...); question begging, circular arguments; complex questions and answers - forms of question begging; vicious circle; ignoring the point, e.g. Macaulay on 15 years of Charles 1st's reign and his apologists]

EDUCATIONAL IDEAS ['Transfer of learning' idea from, say, Latin: p 121: "There is no evidence for it, though primary and secondary education established for 2 and 1 generation". FAINT SUGGESTION that people wanted scientists, or rather technologists, not classics. "Politicians praised 'glorious incapacity.'" APPROVAL FOR severe training, strenuous exercise, strict discipline, plain fare—though without clearly stating what was meant.

Most of the longish passages are (I'd guess) part of Jepson's teaching of history.

He has pages on the meanings of words: 'democracy' from Greeks, French Revolution, 19th Century England, World War 1, and the present day, all in completely conventional style. Pages 48-52 look at meanings of law, justice, liberty, equality. Jepson looks at non-English wars: the Spanish Civil War, the Franco-Prussian war, cartoons of Germans as tiny, with huge helmets or big and bearded singing Lutheran carols around Christmas trees. And the myth of Russian soldiers landing in Scotland in World War (he doesn't mention the 'Angel of Mons')—perhaps a PsyOp in modern parlance.

Jepson on the Constitution of the U.S.A. (page 150): ‘A mistaken analogy led to the present from of the Constitution of the U.S.A. Those responsible for framing it set out to imitate certain characteristics of the English Constitution. But in their estimate of it they overrated the influence of the Crown in the person of George III—an influence due to transitory causes only—and they paid more attention to the theory of the Constitution, as explained by the lawyer Blackstone, than to its working in practice. Hence they created a strong executive (representing the Crown in England) and carefully separated the three departments of government—the executive, the legislative, and the judicature; but they neglected the fact that in actual practice in England those holding the highest executive posts sit in Parliament and are responsible to it for the conduct of their official duties.’

Jepson on some historic parallels: ‘.. world civilization.. a series of ... stages.. rugged strength, graceful beauty, and excessive ornamental elaboration. .. Doric, Ionic and Corinthian.. Norman, Early English, and Decorated.. bourgeois or middle-class revolt, a "reign of terror", and .. military dictatorship.. war, boom, depression evident in the first half of the nineteenth century, appeared to be repeated in the years 1914-1934...

Suggestive stuff, though of course difficult. And many omissions suggest, at least to me, Jewish evasion—what about black slavery by Jews, Opium Wars by Jews, British Empire's ships being Jewish, Jews used to extort money?

The chapter PREJUDICE includes this section: ‘... we should experience some difficulty [on reading recent history] in, shall we say, tracing the causes of war; for, according to them, all wars are due to international financiers, Jews, armament firms, imperialism, oil trusts, Jesuits, democracy, dictators, communists, individualists, foreigners, the English, the Press, education, boosting the birth rate, Catholicism, Freemasons, lawyers, or drink. Such people shrink from the special effort required to take account of negative evidence; ...’

I had a lot of sympathy for this book, but this emotion is probably very misplaced. At that time of depression, poverty, the results of family deaths and loss of family businesses to the state. It seems to resemble the outlook in post-1945 Jew-controlled countries, of new horizons denied to the benighted parental generation who were thought of as uneducated. Certainly it did nothing much to advance thought.

I'll list a very few of his examples of confusions of thought; amusing, but perhaps unhelpful:–

A bogus Biblical quotation, made up by someone in Ireland: "'The land belongeth to the tenant, and not to the landlord', saith the Lord."

The British Empire has been built up, brick by brick and stone by stone, cemented by the blood and sweat of successive generations of our countrymen. Remove one of these stones or bricks, and the whole edifice will collapse."

"Cupping" or blood-letting is a recognised method of curing some bodily ailments. Wars, too, acts in the same way. It is a blessing, not a curse. What country ever became great without blood-letting?

"The Allied fortunes in the War began to improve soon after America joined them. Therefore America won the war."

SIR, I have no use at all for these newfangled notions in Education - free discipline, self-determination and so on. Look at the results. A lot of Bolsheviks, shiftless wasters, with no respect for authority or anything else for that matter. Give me the good old-fashioned discipline. If you spare the rod, you spoil the child. Besides, everyone knows the average boy likes strict discipline: he respects those who wield it. He knows that it does him all the good in the world. Yours, etc.

This scheme aims at an improvement in our system of education. But it is universally admitted that our educational system has been steadily improving; therefore this scheme is superfluous.

"I knew a man who spent a lot of money on the education of his daughter and she went and married a Chinaman."

"It is curious the number of parents insisting that their children learn Economics. There never was a more futile subject. It leads nowhere. And a good many come from Economic Schools half-developed Socialists and good for little. Keep away from it."

You must stand either for the protection of social privilege and private vested interests, or for the principle of human brotherhood and the common good.

The scarcer an article, the more valuable it is; in order to be wealthy, therefore, society should try to make things scarce.

Protectionist: And then you say that Protection raises prices. Why, ever since the introduction of tariffs after the financial crisis of 1931, prices have actually fallen, and many staple foods actually cost less today than they did in the palmy days before the Great War. That shows that tariffs have actually lowered prices.

The total wealth of a country has to be divided between workers and property owners. Obviously, what is taken from one is given to the other.

The McKenna duties have obviously benefited the Motor Trade; our production of cars has gone up by leaps and bounds, and the motor manufacturing industry now occupies a place among the first five important industries in G.B. The heavy industries - iron and steel - are now recovering quickly under the recent protection afforded them. The farmer is benefiting from the restriction in the imports of agricultural produce. It follows, therefore, that if all the products of this country were similarly protected, all classes in the community would feel the benefit.

Money is the source of happiness and comfort. If everybody had more money, the whole world would be a happier and more comfortable place.

Two of the most valuable things in life are air and light; yet they cost nothing.

Why all this outcry against the Capitalists? The humblest workman's bag of tools is capital; everyone with only a few shillings in the Savings Bank is a Capitalist.

Periods of monetary inflation are periods of active trade, little employment, rising wages, and high profits. Why not issue lots of paper money and so produce this desirable state of affairs?

I believe in improving the condition of the poor, but the trouble is that if you make them better off, they only multiply faster, and thus keep themselves in their old condition of poverty.

"Foreign travel is good for everybody, but it cannot be forgotten that behind all this anxiety to send children holiday-making on the Continent, is the intention to turn them into priggish little internationalists, the friends of every country but their own."

X was one of the best statesmen the country has ever had, for during his period of office we enjoyed a degree of prosperity unparalleled by anything before or since..

"You talk of the millionaire's luxury yachts, and shooting boxes, and deer forests, and armies of servants - and say such luxuries are needless and harmful. How would you like to give up your wireless set and your weekly visit to the cinema? Aren't they luxuries too?

1936 A. E. Mander: 'Clearer Thinking: Logic for Everyman'

Alfred Ernest Mander (1894-1985) may have been Jewish. He had a mixed background; however I've learned to deeply distrust online biographies. This book was published by Watts & Co, at least in Britain, number 57 in the Thinker's Library. This series (related to South Place Ethical Society) published books by Wells, Haeckel, Bradlaugh, Darwin, Joseph McCabe and others, on similar principles to George Allen & Unwin's paperbacks after WW2. They had a definite, but very muted, secret Jewish bias—in line with all broadcasting, publishing, education, and religion.

The first publication date, 1936, suggests competition with Jepson, but I don't know the story, if any. But I'd guess, from the rather large typeface and the use of capitals, and thickish paper, that Mander's book was a rushed job. It seems to me to be bitty and fragmented.

Mander has a practical attitude to thinking, which looks very different from Jepson's, though the outcomes aren't very different, since neither is radical in the true sense. Mander might produce trade union speakers, and Jepson's Tory types, but neither would get to the roots.

Mander starts ‘Thinking is skilled work. It is not true that we are naturally endowed with the ability to think clearly and logically—without learning how, or without practising. It is ridiculous to suppose that any less skill is required for thinking than for carpentering, or for playing tennis, golf, or bridge, or for playing some musical instrument. ... as a people, we are so much less efficient in this respect than we are in our sports. ...’

Mander is keen not just on thinking, but outputting thoughts to his audiences: Most speakers and writers use far too many words. They obscure their thought with great masses of verbiage. Usually it is possible to re-write a passage—expressing every essential point with clarity and precision—in one-half, one-third or one-quarter of the number of words. Mander gives a 9-point suggested process to work through any passage to check the "facts" and the reasoning. He has a section VII THEORIES where he starts from "It's all right in theory [not OK, back then!} but it doesn't work out in practice", ridicules that form of words, and goes on to discuss testing of theories—including 'general' and 'special' theories. Mander has a section on the RECOGNIZED EXPERT AUTHORITIES which resembles the 'peer group' idea in modern academia, though Mander has doubts which seem correct: he wants actual name(s), recognition as an expert authority, preferably alive, and unbiassed. if there is AGREEMENT among most of the expert authorities, then we may assume that their various interests and prejudices cancel out ... Um, well. The book is unindexed, and has an Appendix on Determinacy and cause; it has the concept of probability, but not probability distributions.

Mander, in a section entitled 'Evolution': ‘During the last few generations, man has made a discovery the importance of which it is difficult to over-estimate. It is this: that nothing can be fully understood except by reference to its context. .. all things are largely unintelligible—if we consider only the facts at any given instant of time. .. like going into a cinema in the middle of a picture.. glancing.. and coming out. What we should see would be unintelligible. Perhaps a horseman.. with one foot in the stirrup,.. looking.. at a square black box on the ground; .. a policeman, his clothes dripping water, rushes from a house.. carrying a dead goose.. Similarly.. to understand the present, we must know something of the past out of which it has grown. This truth.. though it now seems obvious, is really quite new to man .. But already it has revolutionized the whole thought of educated, civilized people. To-day we try to see almost everything in the light of its history.. in its new sense of one thing leading to another. ..'

H G Wells credited Marx with having this conception; — in New Worlds for Old he says Marx invented it. Possibly The Outline of History would not have existed unless Wells believed something like that. Or perhaps not!

I can think of at least two 'important discoveries'—the discovery of suspended judgment, and the discovery of the idea of evolution. Mander doesn't really explain how such discoveries could be tested.

'Children, savages, and the majority of persons.. are content to take things as they find them. ... The desire to understand.. things.. is not a desire that comes early in the development of either the individual or the race. It is remarkable how incurious primitive savages are. About as incurious as is the average lady motorist about what is under the bonnet of her car! Or the average man about what is going on under his own hat!'

Primitive man's beliefs were permitted by lack of knowledge:] ‘[found it].. not.. incredible that a stick might become a snake; the the Nile might rise in answer to prayers..; that a donkey might begin speaking Hebrew; that the sun might "go out" at the bidding of.. Christopher Columbus..; that mountains in New Zealand might quarrel..; that Buddha might be begotten in his mother by a ray of moonlight..’

Mander is refreshing, but shies away from serious discussions on wars, law, industry, raw materials. So his book turns out to be rather limited. Perhaps he added 'Logic for Everyman' to his title as an acknowledgement of this limitation.

1938 R. W. Jepson, 'Teach Yourself to Think'