A Short History of the World by Herbert George Wells

First Published 1922. Heinemann edition 1927. Penguin edition 1946. Revised Penguin Edition 1965. No index.

Assessing the influence of Wells’ Historical Works from c. 1920

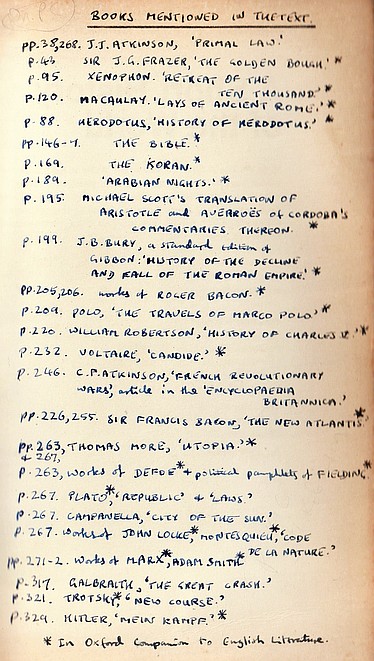

Books noted in all editions (I think) to hint at some of Wells' sources

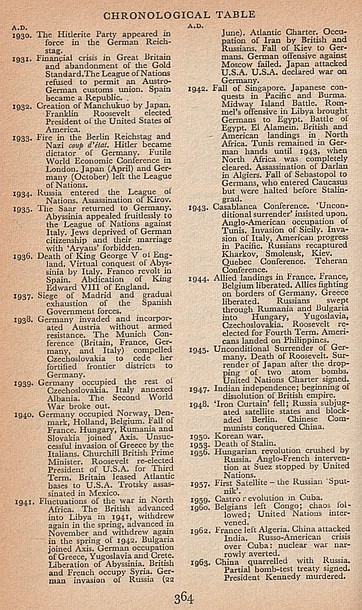

Chronological table from 1965 Penguin edition. The earliest copy's chronology extended to 1922 .. defeat of Greeks by Turks. Most or all of this by Raymond Postgate and G P Wells

Example of a Jew-naive commercial publication, Dorling Kindersley Ltd, part of Penguin Books Random House. A 2014 'Visual Guide' to the 'Great War'. No doubt special-made with dozens of hacks, to commemorate 1914. Jews aren't even listed in the index. Nothing about paper money. Nothing even on the Dreyfus Affair to show the part played by then-modern media. Just an example of the tenacity with which Jews continue to lie.

I noticed at that time a copy of Private Eye, printed in England and utterly Jew unaware. The same comment on continuity of lies obtains.

In view of the Jewish hold on print and publishing, we must assume Jews encouraged this. Just as they must have liked Belloc's falsely assigning repugnance to the 'Great War' by Jews. A Short History of the World has also had an extensive sale.’

That's all I could find by Wells on his Short History, which I presume was much cheaper, and aimed at people with less disposable cash. But perhaps they were less interested in history, or found it difficult or irrelevant, or had religious objections.

On his Outline, I've given a lot of research effort sparked by a book on Wells by McKillop, a Canadian Roman Catholic who took the side of Deeks, a Canadian woman who sued Wells for plagiarism. See this pdf file West on McKillop on Wells for information on Wells's book, at that time in two volumes. And see H G Wells on the Jewish Influence for extracts from Wells. And why not Jewish Propaganda Books of this period.

Wells' Short History has the characteristic of describing things which were rather visible, or obvious, or understandable. He's not good on things which are hidden, or secret, or vague, or elaborated, or censored in some way. I'll try to wrestle with that. His strength was giving all peoples "a fair shake of the whip", as I've heard it put, which historians generally didn't, then or now. On this point, see his booklet The New Teaching of History. But his work can also seem shadowed at all points by Jewish opinions, often of great age.

Apart from Wells's first 9 or 10 chapters on cosmology and evolution, Jewish versions of history have been applied in all periods so far, it has to be said; the histories of Egypt and Babylon are as reported by Jews; Greece and Rome were shadowed by Jews; Christianity and Islam turn out to be Jewish; modern times including the spread of Christianity by force, and such events as Cromwell and Dutch William and the founding of both the Bank and Church of England. The planning of much of the moves into the western hemisphere were Jewish. So were most big wars.

That's looking back from about 2000 AD. But Wells wasn't aware of much of that, although it crept into the margins of his field of view, and his associate Hilaire Belloc made some attempt to enlighten him.

Another important general characteristic of Wells was his failure to understand or explain large organisations. It's not very obvious why people should obey others, or the strength of such obedience. Wells takes it as given that the man at the top could direct fairly freely what was to be done. But in practice there must have been many events which were incalculable and impractical. And Wells understates legal or habitual practices, which may need awareness of different nations, groups, languages, and professions. I can't blame Wells for this; it's a problem in common for anyone claiming to be a sociologist.

His books on history made a stir—which must partly have been artificial—from about 1920 to about 1940; Wells died after the Second World War, but his Short History, was still going strong in 1965, 'revised and brought up to date by Raymond Postgate and G P Wells'. Below, I've shown one page from the chronology, after 1930, updated, which could have been taken from newspaper headlines, and is now seen to be hopelessly unreliable.

Wells must have influenced many people for something like 50 years. Popular views of what history is must have been significantly influenced by his books, perhaps even more by the short version. The post-1945 mass university constructions finally submerged him, under chunks of specific history, largely written by Jews. Here's just one example, G R Elton on Reformation Europe.

Looking over Wells's histories, it's clear that they are largely the accumulated floor-sweepings of Jewish tales after anything unfavourable had been removed, including mentions of Jews. And the same process was repeated indefinitely, and is being repeated now.

It is undeniable that Wells missed very serious aspects of true history, and may have set back serious study for decades. It seems unlike that perceptive views would have been tolerated, though it's conceivable. So I have to conclude that opponents of Wells were right; he was not a great man and not a great innovator, and helped harm the world by avoiding spotlighting Jews.

Belloc's book The Jews was published first at about the same time as The Outline of History and of course had a strong Roman Catholic tinge. But it also had Jewish informational material. 'This deliberate falsehood equally applies to contemporary record.

The newspaper reader is deceived so far as it is still possible to deceive him with the most shameless lies. "Abraham Cohen, a Pole"; "M. Mosevitch, a distinguished Roumanian"; "Mr. Schiff, and other representative Americans"; "M. Bergson with his typically French lucidity"; "Maximilian Harden, always courageous in his criticism of his own people" (his own being the German) ... and the rest of the rubbish.'

Massacres in Cyprus and Libya in the Roman Empire make another of Belloc's examples; he says ‘One might pile up instances indefinitely. The point is, that the average educated man has never been allowed to hear of them.’ Belloc did not, in practice, pile up instances. Nor did he indicate his sources.

Wells never emphasises the extraordinary grip of Jews on non-Jews, and the processes by which the 'goyim' are made to pay for their own parasites. A perfect example is churches, which became landowners with rich officials, paid by tithes and other sources of money, while Jewish onlookers lived in urban ghettoes doing their best to swindle them. In exchange for keeping records of the people and their official marriages and other things. Somewhat like the BBC, which also started about 1920.

But there are flickerings of recognition of serial stratagems: '... The stresses that arose from the unscientific boundaries planned by the diplomatists at [the Congress of] Vienna .. [account of difficulties in multiracial boundaries] ... he will see that the gathering seems almost as if it had planned the maximum of local exasperation.' Sounds like Versailles after the 'Great War' which happened only after Wells was 50.

Another flickering is in the chapter on The Uneasy Peace in Europe, following The French Revolution chapter. ‘After Louis XVIII died (1824), Charles X set himself to ... restore absolute government, the sum of a billion francs was voted to compensate the nobles for the chateau burnings and sequestrations of 1789. ...’ suggesting parallels with the Restoration in England and compensation for slave-owners.

Other notes which I found:

-Unindexed; but it does have a short chronology, starting 800 BC

-Wells carefully says in his preface this isn't a condensation of his Outline of History, but is planned and written afresh; presumably therefore the chapter headings came first & are a cut-down or conflated version of the Outline's chapter headings.

The Short History has twice as many chapters as the Outline, but they are not subdivided, the resulting book being about three-tenths the length, the extra being made up by miscellaneous details. The chapters and sections are of about equal lengths, which evidently Wells liked. The result is that the Short History looks direct and straight through; while the Outline is discursive and interesting, but with lost threads.

-Originally published by the 'Thinkers Library' with red hard cover, with a rather inky black impression of Rodin's 'Thinker' as logo

-In 24 years, Wells altered and expanded his final chapters; and after his death this process was continued unintelligently.

I bought a 1927 edition (from which I found the number of maps in the 1965 edition was much greater; they'd been taken from 'The Outline..')

And I found a copy of the 1946 Penguin, which has added chapters LXVIII The Failure of the League of Nations, LXIX The Second World War, LXX The Present Outlook for Homo Sapiens which is a very brief chapter, then LXXI 'Mind at the End of its Tether' dated 1940-1944, which begins with a summary of Second World War up to 1944; or so it says; in fact to end of 1941. Its chronological table is of course a bit lengthened.

Penguin edition first in 1946; the 1965 Penguin revision by G P Wells and Raymond Postgate makes it hard to guess at original text, which isn't marked. For example, Leakey is mentioned, and so is Pluto though I think neither was known in 1922.

-Even so, interesting to try to analyse assumptions; e.g. [and see above, on Outline..] it's pre-plate tectonics, pre-relativity, continually talks of evolution as aiming higher, has no concept of 'Celts' or much on megaliths, is Eurocentric (though less than is usual & with parallels with say China. And there is a warning about possible discoveries in Africa and Asia; and Buddhism and a few other Asian things are given space), perhaps has Biblical attitude to 'Semites': 119: 'So ended the Third Punic War. Of all the Semitic states that had flourished.. five centuries before .. free.. only Judea.. Carthaginians, Phoenicians and kindred people.. to a large extent they were still the traders and bankers of the world..'; spins conclusions from slender evidence e.g. on human sacrifice and cannibalism and I think savages, or on small horses being a favourite food, regards 'primitive' men as thinking in a way which is 'childlike' somewhat along the idea that embryos repeat evolutionary development, has tree of 'true men' with negroes then 'Nordic', 'Mongolian' and 'Brunet with Heliolithic culture' divisions of mankind, assumes I think (as in 'Mind at the End..') that primitive men were much bigger, has Bible-like idea that only the last few thousand years count, assumes agriculture preceded settlements, has a bias towards empires, gives little weight to inventions and discoveries, preferring religion etc; religion is assumed to be indefinitely old, perhaps reflecting Christian propaganda. It's interesting to consider the projection of current attitudes and interest groups back: e.g. the emphasis on the Roman Empire rather than say central Asian empires might be considered part of the influence of Christianity; cf the expression 'Judeo-Christian'; with a few adjustments it could have been perhaps 'Nilotic-Parsee' or 'Persian-Semitic' or something.

Another traditional thing taken over from ordinary histories is the idea of 'big men', so discussion of who carries out their commands etc is ignored - possibly to avoid criticising the workers? Possibly because it was taken for granted that people do what they're told? - I'm not sure, but it's a considerable omission. See e.g. the notes below on the four stages of the rise of the Roman Empire.

An interesting point is that his concentration on increasing travel and communication is treated as more or less a good thing: the correlative rise in empires and oppressions, and also side-issues like passports and customs, are almost ignored.

Quite difficult to remember what happened in the 'intellectual' world after he wrote this: I think Tawney post-dated it with the Protestantism and capitalism stuff; certainly Beveridge; and certainly much of McCabe.

-I recall George Orwell/Eric Blair had three comments on 'Outline of History': first, Wells disliked the influence of horses, and seemed hostile to e.g. tribes who rode or fought with them; and he disliked Napoleon; and he elevated the USA.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS OF WELLS'S SHORT HISTORY OF THE WORLD:

1 WORLD IN SPACE

2 WORLD IN TIME

3 BEGINNINGS OF LIFE

4 AGE OF FISHES

5 AGE OF COAL SWAMPS

6 AGE OF REPTILES

7 FIRST BIRDS AND FIRST MAMMALS

8 AGE OF MAMMALS

9 MONKEYS, APES AND SUB-MEN

10 NEANDERTHAL AND RHODESIAN MAN

11 FIRST TRUE MEN

12 PRIMITIVE THOUGHT

13 BEGINNINGS OF CULTIVATION

14 FIRST AMERICANS

15 SUMERIA, EARLY EGYPT, AND WRITING

16 PRIMITIVE NOMADIC PEOPLES

17 FIRST SEA-GOING PEOPLES

18 EGYPT, BABYLON, ASSYRIA

19 PRIMITIVE ARYANS

20 LAST BABYLONIAN EMPIRE AND EMPIRE OF DARIUS I

21 EARLY HISTORY OF THE JEWS

22 PRIESTS AND PROPHETS IN JUDEA

23 THE GREEKS

24 WARS OF GREEKS AND PERSIANS

25 SPLENDOUR OF GREECE

26 EMPIRE OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT

27 MUSEUM AND LIBRARY AT ALEXANDRIA

28 GAUTAMA BUDDHA

29 KING ASOKA

30 CONFUCIUS AND LAO TSE

31 ROME COMES INTO HISTORY

32 ROME AND CARTHAGE

33 THE GROWTH OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

34 ROME AND CHINA

35 THE COMMON MAN'S LIFE UNDER THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

36 RELIGIOUS DEVELOPMENTS UNDER THE ROMAN EMPIRE

37 TEACHING OF JESUS

38 DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINAL CHRISTIANITY

39 BARBARIANS BREAK THE EMPIRE INTO EAST AND WEST

40 HUNS AND THE END OF THE WESTERN EMPIRE

41 BYZANTINE AND SASSANID EMPIRES

42 DYNASTIES OF SUI AND TANG IN CHINA

43 MUHAMMAD AND ISLAM

44 GREAT DAYS OF THE ARABS

45 DEVELOPMENT OF LATIN CHRISTENDOM

46 CRUSADES AND THE AGE OF PAPAL DOMINION

47 RECALCITRANT PRINCES AND THE GREAT SCHISM

48 MONGOL CONQUESTS

49 INTELLECTUAL REVIVAL OF THE EUROPEANS

50 REFORMATION OF THE LATIN CHURCH

51 EMPEROR CHARLES V

52 POLITICAL EXPERIMENTS: GRAND MONARCHY, PARLIAMENTS, REPUBLICANISM

53 NEW EMPIRES OF EUROPEANS IN ASIA AND OVERSEAS

54 AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

55 FRENCH REVOLUTION AND RESTORATION OF MONARCHY IN FRANCE

56 UNEASY PEACE IN EUROPE FOLLOWING FALL OF NAPOLEON

57 DEVELOPMENT OF MATERIAL KNOWLEDGE

58 THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

59 DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL IDEAS

60 EXPANSION OF THE UNITED STATES

61 RISE OF GERMANY TO PREDOMINANCE IN EUROPE

62 NEW OVERSEAS EMPIRES OF STEAMSHIP AND RAILWAY

63 EUROPEAN AGGRESSION IN ASIA AND THE RISE OF JAPAN

64 BRITISH EMPIRE IN 1914

65 AGE OF ARMAMENT IN EUROPE; GREAT WAR OF 1914-1918

66 RUSSIAN REVOLUTION [Mostly by Wells; after this Wells' contribution drops progressively to nil]

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

NO INDEX

DETAILED CONTENTS of PARTS OF WELLS'S SHORT HISTORY:

LIST OF 22 MAPS, which I've marked as #M in their chapters:-

1 WORLD IN SPACE

2 WORLD IN TIME

3 BEGINNINGS OF LIFE

4 AGE OF FISHES

5 AGE OF COAL SWAMPS

6 AGE OF REPTILES

7 FIRST BIRDS AND FIRST MAMMALS

8 AGE OF MAMMALS

9 MONKEYS, APES AND SUB-MEN

10 NEANDERTHAL AND RHODESIAN MAN [#M Europe 50,000 years ago]

11 FIRST TRUE MEN

12 PRIMITIVE THOUGHT

13 BEGINNINGS OF CULTIVATION [#M; family tree of man]

14 FIRST AMERICANS

15 SUMERIA, EARLY EGYPT, AND WRITING

16 PRIMITIVE NOMADIC PEOPLES

17 FIRST SEA-GOING PEOPLES

18 EGYPT, BABYLON, ASSYRIA

19 PRIMITIVE ARYANS

20 LAST BABYLONIAN EMPIRE AND EMPIRE OF DARIUS I [#M]

21 EARLY HISTORY OF THE JEWS [#M]

22 PRIESTS AND PROPHETS IN JUDEA

23 THE GREEKS

24 WARS OF GREEKS AND PERSIANS

25 SPLENDOUR OF GREECE

26 EMPIRE OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT

27 MUSEUM AND LIBRARY AT ALEXANDRIA

28 GAUTAMA BUDDHA

29 KING ASOKA

30 CONFUCIUS AND LAO TSE

-107-9: 'It is quite possible that the earliest civilization of China was not Mongolian at all, any more than the earliest civilization of Europe and western Asia was Nordic or Semitic. It is quite possible that the earliest civilization of China was a brunet civilization and of a piece with the earliest Egyptian, Sumerian, and Dravidian civilizations. ..

.. as in divided Greece there were philosophers, and in shattered and captive Jewry prophets, so in disordered China there were philosophers and teachers at this time. In all these cases insecurity and uncertainty seemed to have quickened the better sort of mind. Confucius was a man of aristocratic origin and some official importance in a small state called Lu. Here, in a very parallel mood to the Greek impulse, he set up a sort of Academy for discovering and teaching wisdom. .. He travelled from state to state seeking a prince who would carry out his legislative and educational ideas. .. a century and a half later .. Plato also sought a prince..

The gist of Confucius was the way of the noble or aristocratic man. He was concerned with personal conduct as much as Gautama was concerned with the peace of self-forgetfulness and the Greek with external knowledge and the Jew with righteousness. ..

The teaching of Lao-Tse, who was for a long time in charge of the imperial library of the Chow dynasty, was much more mystical and vague and elusive than that of Confucius. He seems to have preached a stoical indifference to the pleasures and powers of the world and a return to an imaginary simple life of the past. .. In China just as in India primordial ideas of magic and monstrous legends out of the childish past of our race [sic; this is one of Wells' themes] struggled against the new thinking in the world and succeeded in plastering it over with grotesque, irrational, and antiquated observances. Both Buddhism and Taoism.. are religions of monk, temple, priest..

North China, the China of the Hwang-ho River, became Confucian in thought and spirit; south China, Yangtse-kiang China, became Taoist. Since those days a conflict has always been traceable in Chinese affairs between these two spirits, .. of the north and.. the south, between (in later times) Peking and Nanking, between the official-minded, upright and conservative north, and the sceptical, artistic, lax and experimental south. ..'

31 ROME COMES INTO HISTORY

32 ROME AND CARTHAGE [#Map]

33 THE GROWTH OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

-121: 'The Roman Empire was a growth, an unplanned novel growth; .. engaged almost unawares in a vast administrative experiment. It cannot be called a successful experiment. In the end their empire collapsed altogether. And it changed enormously in form and method.. It changed more in a hundred years than Bengal or Mesopotamia or Egypt changed in a thousand. .. It never attained to any fixity.

...

.. bear in mind the very greater changes.. There is much too strong a tendency in peoples' minds to think of the Roman rule as something finished and stable, firm, rounded, noble, and decisive. Macaulay.. SPQR, the elder Cato, the Scipios, Julius Caesar, Diocletian, Constantine the Great, triumphs, orations, gladiatorial combats, and Christian martyrs all mixed up together... The items of the picture have to be disentangled. They are collected at different points from a process of change profounder than that which separates the London of William the Conqueror from the London of today.'

-123: [FOUR STAGES:] 'We may.. divide the expansion of Rome into four stages. [FIRST STAGE: ASSIMILATIVE REPUBLIC:] The first stage began after the sack of Rome by the Gauls in 390 B.C. and went on until the end of the First Punic War (240 B.C.). We may call this stage the stage of the Assimilative Republic. It was perhaps the finest, most characteristic stage in Roman history. The age-long dissensions of patrician and plebeian were drawing to a close, the Etruscan threat had come to an end, no one was very rich nor yet very poor, and most men were public-spirited. It was a republic, as far as we can envisage, something like the northern states of the American Union in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; a free farmers' republic. .. Rome was a little state scarcely twelve miles square. She fought the sturdy but kindred states about her, and sought.. coalescence. Her centuries of civil dissension had trained her people in compromise and concessions. Some of the defeated cities became altogether Roman with a voting share in the government, some became self-governing with the right to trade and marry in Rome; garrisons of full citizens were set up at strategic points and colonies of varied privileges founded among the freshly conquered people. Great roads were made. The rapid Latinization of all Italy was the inevitable consequence of such a policy. In 89 B.C. [sic; isn't this outside his range?] all the free inhabitants of Italy became citizens of the city of Rome. Formally the whole Roman Empire became at last an extended city. In A.D. 212 every free man in the entire extent of the empire was given citizenship; the right, if he could get there, to vote in the town-meeting in Rome.

The extension of citizenship to tractable cities and to whole countries was the distinctive device of Roman expansion. It reversed the old process of conquest and assimilation of the conquerors. By the Roman method the conquerors assimilated the conquered.

[SECOND STAGE: REPUBLIC OF ADVENTUROUS RICH MEN:] But after the First Punic War and the annexation of Sicily, .. another process arose by its side. Sicily, for instance, was treated as conquered prey. It was declared an 'estate' of the Roman people. Its rich soil and industrious population were exploited to make Rome rich. The patricians and the more influential among the plebeians secured the major share... And the war also brought in a large supply of slaves. Before the First Punic War the population of the republic had been largely a population of citizen farmers. Military service was their privilege and liability. While they were on active service their farms fell into debt and a new large-scale slave agriculture grew up; when they returned they found their produce in competition with slave-grown produce from Sicily and from the new estates at home. Times had changed. The republic had altered its character. Not only was Sicily in the hands of Rome, the common man was in the hands of the rich creditor and the rich competitor. ..

For two hundred years the Roman soldier-farmers had struggled for freedom and a share in the government of their state; for a hundred years they had enjoyed their privileges. The First Punic War wasted them and robbed them of all they had won.

The value of their electoral privileges had also evaporated. The governing bodies of the Roman Republic were .. first and more important.. the Senate. ... a body originally of patricians and then of prominent men of all sorts, who were summoned to it first by certain powerful officials, the consuls and censors. Like the.. House of Lords it became a gathering of great landowners, prominent politicians, big business men, and the like. It was much more like the British House of Lords than it was like the American Senate. For three centuries, from the Punic Wars onward, it was the centre of Roman political thought and purpose. The second body was the Popular Assembly. This was supposed to be an assembly of all the citizens of Rome. When Rome was a little state.. this was a possible gathering. When the citizenship has spread beyond the confines in Italy, it was an altogether impossible one. Its meetings, proclaimed by horn-blowing from the Capitol and the city walls, became more and more a gathering of political hacks and city riff-raff. In the fourth century B.C. the Popular Assembly was a considerable check upon the senate, a competent representation of the claims and rights of the common man. By the end of the Punic wars it was an impotent relic of a vanquished popular control. No effectual legal check remained upon the big men.

Nothing of the nature of representative government was ever introduced into the Roman republic. No one thought of electing delegates to represent the will of the citizens. This is a very important point for the student to grasp. The Popular Assembly never became the equivalent of the American House of representatives or the British House of Commons. In theory it was all the citizens; in practice it ceased to be anything at all worth consideration.

The common citizen of the Roman Empire was therefore in a very poor case after the Second Punic War; he was impoverished, he had often lost his farm, he was ousted from profitable production by slaves, and he had no political power left to him to remedy these things. The only methods of popular expression left to a people without any form of political expression are the strike and the revolt. The story of the second and first centuries B.C., so far as internal politics go, is a story of futile revolutionary upheaval. The scale of this history will permit us to tell of the intricate struggle of that time, of the attempts to break up estates and restore the land to the free farmer, or proposals to abolish debt in whole or in part. There was revolt and civil war. In 73 B.C. the distresses of Italy were enhanced by a great insurrection of the slaves under Spartacus. The slaves of Italy revolted with some effect, for among them were the trained fighters of the gladiatorial shows. For two years Spartacus held out in the crater of Vesuvius, which seemed at that time to be an extinct volcano. This insurrection was defeated at last and suppressed with frantic cruelty. Six thousand captured Spartacists were crucified along the Appian Way, the great highway that runs southward out of Rome (71 B.C.).

The common man never made head... the big rich men who were overcoming him were even in his defeat preparing a new power in the Roman world over themselves and him - the power of the army.

Before the Second Punic War the army of Rome was a levy of free farmers, who, according to their quality, road or marched afoot to battle. This was a very good force for wars close at hand, but not the sort.. that will go abroad and bear long campaigns... And moreover as the slaves multiplied and the estates grew, the supply of free-spirited fighting farmers declined. It was a popular leader named Marius who introduced a new factor. North Africa after the overthrow of the Carthaginian civilization had become a semi-barbaric kingdom, the kingdom of Numidia. The Roman power fell into conflict with Jugurtha, king of this state, and experienced enormous difficulties.. In a phase of public indignation Marius was made consul, to end this discreditable war. This he did by raising paid troops and drilling them hard. Jugurtha was brought in chains to Rome (106 B.C.), and Marius, when his time of office had expired, held on to his consulship with his newly-created legions. There was no power in Rome to restrain him.

[THIRD STAGE: REPUBLIC OF THE MILITARY COMMANDERS:] With Marius began the third phase.. a period in which the leaders of the paid legions fought for mastery of the Roman world. Against Marius was pitted the aristocratic Sulla who had served under him in Africa. Each in turn made a great massacre of his political opponents. Men were proscribed [COD says: put out of protection of law (esp fig) denounced as dangerous] and executed by the thousand, and their estates were sold. After the bloody rivalry of these two and the horror of the revolt of Spartacus, came a phase in which Lucullus and Pompey the Great and Crassus and Julius Caesar were the masters of armies and dominated affairs. It was Crassus who defeated Spartacus. Lucullus conquered Asia Minor and penetrated into Armenia, and retreated with great wealth into private life. Crassus, thrusting farther, invaded Persia and was defeated and slain by the Parthians. After a long rivalry Pompey was defeated by Julius Caesar (48 B.C.) and murdered in Egypt, leaving Julius Caesar sole master of the Roman world.

[FOURTH STAGE: THE EARLY EMPIRE:] The figure of Julius Caesar is one that has stirred the human imagination out of all proportion to its merit or true importance. He has become a legend and a symbol. For us he is chiefly important as marking the transition from the phase of military adventurers to the beginning of the fourth stage in Roman expansion, the early Empire. For in spite of the profoundest economic and political convulsions, in spite of civil war and social degeneration, throughout all this time the boundaries of the Roman state crept outward and continued to creep outward to their maximum in about A.D. 100. There had been something like an ebb during the doubtful phases of the Second Punic War, and again a manifest loss of vigour before the reconstruction of the army by Marius. The revolt of Spartacus marked a third phase. Julius Caesar made his reputation as a military leader in Gaul, which is now France and Belgium. (The chief tribes inhabiting this country belonged to the same Celtic people as the Gauls who had occupied north Italy for a time, and who had afterwards raided into Asia Minor and settled down as the Galatians.) Caesar drove back a German invasion of Gaul and added all that country to the empire and he twice crossed the Straits of Dover into Britain (54 and 54 B.C.) where, however, he made no permanent conquest. Meanwhile, Pompey the Great was consolidating Roman conquests that reached in the east to the Caspian Sea.

At this time, in the middle of the first century B.C., the Roman Senate was still the nominal centre of the Roman government, appointing consuls and other officials, granting powers and the like; and a number of politicians, among whom Cicero was an outstanding figure, were struggling to preserve the great tradition of republican Rome and to maintain respect for its laws. But the spirit of citizenship had gone from Italy with the wasting away of the free farmers; it was a land now of ##### radio play

34 ROME AND CHINA

35 THE COMMON MAN'S LIFE UNDER THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

-136: 'A rich man would have a Greek slave as a librarian, and slave secretaries and learned men. He would keep his poet as he would a performing dog. In this atmosphere of slavery, the traditions of modern literary scholarship and criticism, meticulous, quarrelsome, and timid, were evolved. There were enterprising people who bought intelligent boy slaves and had them educated for sale. ...'

-137: '.. Restrictions upon cruelty were made, a master might no longer sell his slave to fight wild beasts, a slave was given property rights in what was called his peculium, slaves were paid wages.. a form of slave marriage was recognized. ..'

[My footnote, no doubt from COD, says 'private property: derived from pecu, cattle; same stem as pecuniary.' I didn't compare this with Africa; nor did I add it's presumably the same stem as 'peculiar']

36 RELIGIOUS DEVELOPMENTS UNDER THE ROMAN EMPIRE

37 TEACHING OF JESUS

38 DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINAL CHRISTIANITY

39 BARBARIANS BREAK THE EMPIRE INTO EAST AND WEST [#M]

40 HUNS AND THE END OF THE WESTERN EMPIRE

41 BYZANTINE AND SASSANID EMPIRES

42 DYNASTIES OF SUI AND TANG IN CHINA

43 MUHAMMAD AND ISLAM

44 GREAT DAYS OF THE ARABS [#M; two maps showing expansion]

45 DEVELOPMENT OF LATIN CHRISTENDOM [#Map of Franks at time of Charles Martel; map of Europe at death of Charlemagne]

46 CRUSADES AND THE AGE OF PAPAL DOMINION

47 RECALCITRANT PRINCES AND THE GREAT SCHISM

48 MONGOL CONQUESTS [#M]

49 INTELLECTUAL REVIVAL OF THE EUROPEANS [#M]

50 REFORMATION OF THE LATIN CHURCH

51 EMPEROR CHARLES V

52 POLITICAL EXPERIMENTS: GRAND MONARCHY, PARLIAMENTS, REPUBLICANISM [ Europe after Peace of Westphalia]

53 NEW EMPIRES OF EUROPEANS IN ASIA AND OVERSEAS [#M of America 1750]

54 AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE [#M of settlement in 1790]

55 FRENCH REVOLUTION AND RESTORATION OF MONARCHY IN FRANCE

56 UNEASY PEACE IN EUROPE FOLLOWING FALL OF NAPOLEON

-[#Map of Europe after the Congress of Vienna]

57 DEVELOPMENT OF MATERIAL KNOWLEDGE

58 THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

-[Note: this distinction also in his discussion on Marx in '.. Clissold':] 'There is a tendency in many histories to confuse together what we have called the mechanical revolution, .. an entirely new thing.. arising out of .. organized science, a new step like the invention of agriculture or the discovery of metals, with something.. quite different.. for which there was .. a precedent, the social and financial development.. called the industrial revolution. The two processes were going on together, .. but .. were in.. essence different. There would have been an industrial revolution of sorts if there had been no coal, no steam, no machinery; .. would have repeated the [late Roman republic] story of dispossessed free cultivators, gang labour, great estates, great financial fortunes, and a socially destructive financial process. Even the factory method came before power and machinery. Factories were the product not of machinery, but of the 'division of labour'. .. workers were making such things as millinery, cardboard boxes and furniture, and colouring maps and book illustrations.. before even water-wheels had been used for industrial purposes. There were factories in Rome in the days of Augustus. New books, for instance, were dictated to rows of copyists.. The attentive students of Defoe and of the political pamphlets of Fielding will realize that the idea of herding poor people into establishments to work collectively for their living was already current in Britain before the close of the 17th century. There are intimations.. as early as More's Utopia (15126). It was a social and not a mechanical development.

...

The mechanical revolution, the process of mechanical invention and discovery, was a new thing.. and it went on regardless of the social, political, economic and industrial consequences it might produce. ..'

59 DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL IDEAS

60 EXPANSION OF THE UNITED STATES [#M of USA]

61 RISE OF GERMANY TO PREDOMINANCE IN EUROPE [#M Europe 1848-1871]

62 NEW OVERSEAS EMPIRES OF STEAMSHIP AND RAILWAY [#M British Empire 1815]

63 EUROPEAN AGGRESSION IN ASIA AND THE RISE OF JAPAN

64 BRITISH EMPIRE IN 1914

-297: 'The .. material progress .. that created this vast steamboat-and-railway republic of America and spread this precarious British steamship empire over the world produced quite other effects upon the congested nations upon the continent of Europe.. confined within boundaries fixed during the horse-and-buggy period.. Only Russia had any freedom to expand eastward [map shows European Russia, and huge Siberia].. All these nations armed. Year after year .. At last it came. Germany and Austria struck at France and Russia and Serbia; the German armies marching through Belgium, Britain immediately came into the war on the side of Belgium, bringing in Japan, as her ally, and very soon Turkey followed on the German side. Italy entered the war against Austria in 1915, and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in the October of that year. In 1916 Rumania and in 1917 the United States and China were forced into war against Germany. The more interesting question is not why the Great War was begun, but why [it] was not anticipated and prevented. It is a far graver thing for mankind that scores of millions of people were too 'patriotic', stupid, or apathetic to prevent the disaster by a movement towards European unity upon frank and generous lines, than that a small number of people were active in bringing it about. ...'

65 AGE OF ARMAMENT IN EUROPE; GREAT WAR OF 1914-1918

-#Map overseas empires of European powers, Jan 1914

66 RUSSIAN REVOLUTION [This chapter is mostly by Wells; after this Wells' contribution in the 1965 Penguin edition drops progressively to nil]

-[Has account of Revolutionary Russia under military attack: many states etc listed, including Japan, Poland, Britain. Survival attributed mostly to peasant support.]

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

NO INDEX

Rae West Uploaded 13 Feb 2023