History of the Nineteenth Century by Bertrand Russell and Patricia Spence. Impelled by Russell's affection for Victorian England, and by the disaster of the 'Great War'. But totally ignorant of facts about Jewish and other finance, and costs of important events.

[This book was reissued in 1965 by George Allen & Unwin as an Unwin Paperback in two volumes, 'Legitimacy versus Industrialism 1814-1848' and 'Freedom versus Organization 1776-1914'. I don't know if there were changes in the text.

Allen & Unwin seem to have added 1814-1848, which does not appear in the original. Revolutions in 1848 barely appear in the first edition and its following impressions.]

Added 16 May 2020: The following extract is from Miles W Mathis's piece, rubyridge.pdf (dated May 13, 2022):

It's possible that Russell's book-to-be was a worry for the Jewish overseers; maybe Patricia Spence (birth name Marjorie, by the way) was sent to avoid giveaways about Jews. Bear in mind the date, 1933, and the planting of Hitler, and building of Freemason's Hall in London, and the astonishing Jewish plunders in the eastern hemisphere, which we now see had ramifications in both China and Japan. Spence's work, ('... half the research, a large part of the planning, small portions of the actual writing, ... [and] innumerable valuable suggestions') and what she took from Oxford, is not given at all. Ronald Clark for example has a lot of detail on Russell's chaotic 'love life', but says nothing about the inputs to Russell's history book. His outline plans are described to his publisher, who of course would head Russell off.

A good example of the possible practical effect is the first chapter, on the Congress of Vienna, on which Kissinger wrote a PhD. The Rothschilds are believed to have threatened, or offered, some control over Europe, which Russell avoided, very possibly assisted by Peter Spence's 'research'. His bibliography avoids the few books which pointed to Jewish manipulations: Belloc, Nesta Webster for example. The USA Federal Reserve is omitted. So are such names as Bernard Baruch. The US 'Civil War' is treated as if slavery was the real issue.

If Russell was viewed a a potential truth-seeker, Jewish schemes might have been imperilled. Peter Spence may have had a critical role in smothering Russell.

(It occurs to me that George Spencer Brown, author of Laws of Form, a book praised highly by Russell, may have been praised because of an aristocratic connection).

|

Bertrand Russell on the 19th Century

Russell seems to have taken his history very seriously; few thinkers have written long and detailed books of his sort. (I'm avoiding the possibility that he was just another liar for Jews). I'll try to explain here how Jew practices fill in many puzzles left by his books, in the light of post-2000 Jew awareness.

Readers wanting a summary of Russell on the 19th century should look at his Conclusion at the end of his main text. It is short, and without Russell's long and second-hand intellectual portraits of individuals and their supposed ideas.

Russell knew nothing of the 'Kehila' (or other spellings) system. If he had, he might have wondered if the dominance of Europe might have led to a more opulent version. And this would have included, not just towns, but nations. Hence Hegel on Stadts, expanded into States.

Russell was incurious as to the final effects of algorithms of behaviour, as exemplified by the Talmud. Its endpoint is a 'Moschiah'. But what happens next? It is analogous to the case of people obsessed with making money. If they make it, what do they do next? Russell was not very good on legal subtleties. After a few centuries of what seemed stable laws, new changes were taking place in the way 'democracy' was operated. 'Representative government' was turning into something not at all representative of the electorate.

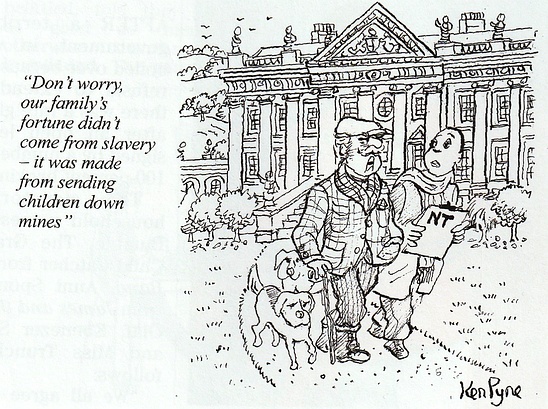

Cartoon 2021. I don't know if it had precursors.

Here's Russell summarising material on 'the slave trade' but also child labour:

The English attitude about the Slave Trade is a psychological curiosity, since the very men who did most for its abolition opposed every attempt to mitigate the horrors of English industrialism. The only concession that such men as Wilberforce were prepared to make on the subject of child labour was that children should have time on Sundays to learn the truths of the Christian religion. Towards English children they were pitiless; towards negroes they were full of compassion. I do not care to suggest an explanation, since the only ones that occur to me are intolerably cynical. But the fact deserves to be noticed, as an outstanding example of the complexity of human sentiment.

It's known now that Jewish racial feelings are anti-non-Jew. Anti-white, and anti-black—except where they think they can benefit. They weren't 'full of compassion' to negroes! Russell says nothing about slavery of whites, or ownership of slave ships by Jews. And it's known now that we should follow the money, including payments made to people such as Wilberforce by Jews over a long period, with arrangements to keep quiet. It's also known now that Jewish ownership of publicity can suppress information more-or-less indefinitely. I give some extracts from Russell, for example on Rockefeller and Marx, and Marx's alleged expulsions, which show Russell as almost unbelievably gullible. Russell's Freedom and Organization says at one point that no European government wanted the 'Great' War. In fact, of course, Jews wanted war and worked for it. Russell seems unaware of the powerful appeal that money has for supposedly religious types. See for example my review of Mrs Sherwood's The Fairchild Family. I don't want to labour the point here. I urge readers to read Russell sympathetically, but try to step back and see where he might have been misled. Try to understand the impact of the Jewish 'Bank of England' when it was new. Try to grasp the psychology of the Kahal, and the way it was expanded as it became clear that Europe was leading the world. See if you can guesstimate profits to be made from financiers of wars. Understand the ways in which secret societies, freemasons, academics, writers can be made into paid corrupted agents. Understand how religions can be cover for payments. Understand how money can turn thugs into mercenaries. Understand how vague rhetorical flourishes can conceal horrors. Be aware that Jews change names, addresses, life experiences. Even if you see no option but co-operate with people selling lies, at least understand what you're doing. |

I'll list here the contents (capitalisation in the original) PART ONE: The Principle of Legitimacy I. NAPOLEON'S SUCCESSORS II. THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA III. THE HOLY ALLIANCE IV. THE TWILIGHT OF METTERNICH PART TWO: The March of Mind Section A: The Social Background V. THE ARISTOCRACY VI. COUNTRY LIFE VII. INDUSTRIAL LIFE Section B: The Philosophical Radicals VIII. MALTHUS IX. BENTHAM X. JAMES MILL XI. RICARDO XII. THE BENTHAMITE DOCTRINE XIII. DEMOCRACY IN ENGLAND XIV. FREE TRADE Section C: Socialism XV. OWEN AND EARLY BRITISH SOCIALISM XVI. EARLY TRADE UNIONISM XVII. MARX AND ENGELS XVIII. DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM XIX. THE THEORY OF SURPLUS VALUE XX. THE POLITICS OF MARXISM PART THREE: Democracy and Plutocracy in America Section A: Democracy in America XXI. JEFFERSONIAN DEMOCRACY XXII. THE SETTLEMENT OF THE WEST XXIII. JACKSONIAN DEMOCRACY XXIV. SLAVERY AND DISUNION XXV. LINCOLN AND NATIONAL UNITY Section B: Competition and Monopoly in America XXVI. COMPETITIVE CAPITALISM XXVII. THE APPROACH TO MONOPOLY PART FOUR: Nationalism and Imperialism XXVIII. THE PRINCIPLE OF NATIONALITY XXIX. BISMARCK AND GERMAN UNITY XXX. THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE GERMAN EMPIRE XXXI. IMPERIALISM XXXII. THE ARBITERS OF EUROPE Conclusion | Bibliography | Index |

Admirers of Russell presumably read this book as another specimen of his style, wit, and insight.

The book is in Russell's modular style, which provides a framework; whether the framework is accurate is another matter. And whether the modules fully match each other, is yet another matter. The book is available free online, and I don't have time or inclination for a full review. Here are some revisionist comments, which readers might find helpful.

• Russell's information is all derivative; he regarded the task of historians as brilliant commentary on spadework done by many others. If they are honest and competent, that's fine. If they miss details, it's less fine—for example, 'capitalism' must have needed travel, communication, legal, geographical, and no doubt other subtleties, which Russell tends to ignore, even if he knew them.

Bibliography: Russell's first chapter on the Congress of Vienna relies on letters and memoirs, I suppose a close thing to original documents if they were well-edited. Russell's chapters on the USA have nothing whatever on developments such as the 'Fed', concentrating on US high finance insofar as it was known to authors. He mentions many books on Germany as a threat; I doubt there are any on encirclement and other menaces. Russell lists only four titles on general history: Treitschke on 19th-century Germany, Lavisse & Rambaud on the 19th century, C A Fyffe on modern Europe, and his military-minded friend G M Trevelyan on 19-century Britain.

Russell's early life, in the final quarter of the nineteenth century, of course left its mark on him.

His arrangement of topics is largely retrospective, as interpreted through English-speaking historians and news sources. So that (for example) the unification of Germany and the 'German Empire' emerge, presumably menacingly to the world.

• Examples: He takes it for granted that the US Civil War was caused by slavery. He assumes the 'Congress of Vienna' (Henry Kissinger allegedly did a PhD on this) was a tussle between European powers, with no Rothschild interest. He regards Napoleon as purely a soldier of fortune—he has no idea of forces behind the 'French Revolution', and generally assumes any war was fought necessarily, because the opponents were unreasonable—the modern model of funding both sides is completely missing. Russell has a rather negligent attitude to law, regarding it as an effect of ideas, rather than a cause of events—when in fact laws may well have long-term consequences, not understood at the time. He doesn't understand the dynamics of religions, taking an established church view that they sit there, doing not much, taking a bit of money, but otherwise harmless and ineffectual.

• Enclosures, Speenhamland Scheme, Poor Laws, Child Labour are described in The Social Background, but for my taste the descriptions are in the 'culture of critique' tradition of carping unhelpful criticism. What should they have done?

• His chapters on the Philosophical Radicals (include Bentham, James Mill and Ricardo, with Francis Place and John Stuart Mill and Francis Burdett and doctrines of Mandeville and Hume and Helvetius in other roles).

From a modern perspective, most of this material is Jew-related if discussed honestly: James Mill worked for the East India Company, probably writing a scrubbed paid history. Ricardo of course was a Jew, who made a lot of money. Bentham's doctrines, for example the greatest happiness for the greatest number principle, and democracy, were probably designed to advance Jews, under the pretext of advancing people generally. Russell is hide-the-Jew oriented all the way through: he hardly mentions the Opium Wars, has a bit on Irish famine, mentions India's penal code (drawn up by Macaulay, he says), has nothing on the Bank of England, says Stonewall Jackson couldn't understand bankers, says little on Jews and the Boer Wars, says nothing about the Ottoman Empire (one of the Jewish Zionist causes of the Great War), and treats aristocracies as self-enclosed, despite continual Jewish penetration.

• On Marx, Russell said in Dear Bertrand Russell you 'will find my opinions on Marx in the relevant chapters' of Freedom and Organization. And Part Two... Section C: Socialism includes four chapters, starting with chapter XVII MARX AND ENGELS. Note that Russell assumed Marx was connected with 'socialism' rather than 'communism'.

• It's fascinating to see Russell's long chapter SLAVERY AND DISUNION, which has nothing on the long-term history of slavery, including of whites, and Jewish ownership and breeding with female slaves in the USA. And nothing significant on race differences: I doubt if Russell spoke seriously to blacks any time in his life. And of course the cause of the US War is simply assumed by Russell to be slavery; he mentions a few legal decisions, such as Dred Scott, but has no idea of the costs of war, and no description of the fantastic destructiveness in the USA.

• Another interesting chapter is XXVIII THE PRINCIPLE OF NATIONALITY. Russell concerns himself mainly with Italy and Germany (of course), but starts with nationalism in England, from Henry VIII. Looking dispassionately, it makes sense to start from the idea that most of the work in any group is everyday; only a fairly small proportion of people look into power structures. I'd suggest, in view of Jewish financial dominance since (say) Amsterdam and the Dutch Empire, Jews were a main force behind nationalism. I'd guess they thought they could bribe and corrupt fewer, more powerful, self-important figureheads than large numbers of smaller ones. The emergence of royal houses and monarchs looks very much connected with Jews, as Cromwell, the death of Charles I, the Bank of England, and the 'Restoration of the Monarchy' with Charles II, show.

The unification of Italy is attributed largely to Giuseppe Mazzini, who supposedly loved Italy, but sent most of his life in England as a writer, somewhat like Lenin. He reads like a typical Jewish writer—vague, impressive-sounding, repetitive, sloganising, designed to be emotionally appealing and flattering to the intended audience. (Russell's Autobiography mentions that Russell possessed Mazzini's watch-case, which had been given to Russell's mother). There's a trick, used for example in Pulitzer Prizes, where someone's account of an event is used to fix it and be quotable; Russell unthinkingly took a similar attitude, ascribing to some traditionally-accepted scribbler the origin of some movement, ignoring deeply-hidden motives.

German unification is described, as might be expected, in a hostile and lengthy manner. Remarkably, Russell omits such events as the hugely destructive Thirty Years War, which I think Hitler omitted to mention too. Fichte reads like Mazzini, but German. Russell is indignant that Treitschke admires the ancient Prussian nobility, who 'obtained every penny of their incomes [from Jews]'. Russell doesn't seem to know that Jews en masse were relatively recent additions to most of the German countryside.

Russell is scathing about Slavs, with their mystic consciousness and dark forests—he doesn't bother to describe them. Russell doesn't seem to think much of long-term survival and endurance and ordinary life.

The whole chapter is worth reading, but in a critical spirit. This is not an easy task.

• A difficult book, since everything in it, including the omissions, is Jew-naive Whig history. Useful as a guide to British official academic (not administrative, not politically-informed) people; it needs careful reading to decode the movements and beliefs and actions, to reveal Jewish machinations. Russell has part of a page on the Affaire Dreyfus, which he presents with complete naïveté. (Read this for the reverse.) Russell was aware that earlier military histories had been made out of date by economic histories, but, in fact, regrettably, he was himself in the same tradition—don't talk about money.

Some Leftover Notes

From about 1980. Since then, awareness of Jews spotlights Russell's limitations. It's even possible that he was a covert Jew carrying out the intentional Jewish lying about all periods of history with Jewish involvement. Note the complete omission of Jews in religions, the invasion of England by Jews arranged by Cromwell, the omission of Jews promoting such ideas as 'bloodless revolution', democracy, 'education', and feeble theories of economics, populations, and government.

• From Ronald Clark's biography: 507: '.. he offered to call it 'One, Two, Three-Bang', remarking that this would be a fairly accurate title. You could add, as a sub-title, "An historico-economic investigation of the Socio-Political causes of the War 1914-1918".'

• From Russell's Preface: 'my collaborator, Peter Spence, who has done half the research, a large part of the planning, and small portions of the actual writing, besides making innumerable valuable suggestions.'

• Scribbles, dated about 1977. May have been taken from talk with George Potter on the 'Whig Interpretation of History'. Nothing (of course) on Jews.

1714: natural ?term of Macaulay's History of Glorious Revolution

1814: end of Napoleonic Empire. - Cult of Napoleon/ Edinburgh Review [this may be mistake for Westminster Review 1824-1907]/ Holland House/ Bradlaugh/ Fox/ Lady Holland/ Macaulay and Whigs etc

1830: 'Bourgeois revolution in France like bloodless revolution in England' moral

1859: Macaulay's death

- Ups and downs of Whig theory - 1688 bloodless Whig revolution (exp. of Stuarts) made England exceptional was the new Whig philosophy etc etc;

PART ONE: LEGITIMACY

[Scenesetting chapters of great interest, though a bit wordy and unwieldy; there are I think only seven men considered. His first chapters are on Napoleon's Successors, and on the Congress of Vienna. His views on the 'French Revolution' and the rise of Napoleon are implicit, and seem conventional. Heinrich 'Henry' Kissinger it seems wrote his PhD dissertation on the Congress of Vienna, which (assuming he was allowed something like full flow,) must have had information on Jews in all the relevant countries, especially Russia. Depressingly, Russell shows a complete absence of awareness of the realities.]

PART TWO: THE MARCH OF MIND [This looks very much like the advance of Jewish ideas - RW] | Section A: The Social Background | V The Aristocracy | VI Country Life | VII Industrial Life

- 55-6 'At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the English were sharply divided into different classes and different kinds of occupation. [The idea of two very different types—as in the start of the Communist Manifesto, is a caricature by Marx and Engels, no doubt copied from earlier writers just one example of the Jewish policy of selecting groups to be made into opponents. Even Russell's book's title is an example - RW] Industrial life, both that of employers and that of wage-earners, was practically unknown to the rest of the community. [sic; note use of 'community'] In the country there were the three classes of landlords, farmers, and labourers. The smaller landlords were country gentry; the larger landlords formed the aristocracy. Political power, ever since the Revolution of 1688, had been almost wholly concentrated in the aristocracy, which, by means of the system of rotten boroughs, controlled the House of Commons as well as the House of Lords. Since about 1760, the aristocracy, by a shameless use of the power of Parliament, had considerably lowered the standard of life among wage-earners. It had also impeded the progress of the middle-class manufacturers, partly from ignorance, partly from jealousy of new power, partly from a desire for high rents. But most of this had been done in a semi-conscious, almost somnambulistic fashion, .. With the beginning of our period, however, a new strenuousness comes into vogue.. earnestness and virtue of the Victorians...'

[Note: doesn't seem to occur to Russell that older methods inevitably must be slower - transport, heating, even cooking, etc, all more difficult and time consuming; 2 that representatives won't be like the people they nominally represent]

- 57-64: [THE ARISTOCRACY]

- 57: 'The Whigs and Tories, the two parties into which the aristocracy was divided, had originally been composed, respectively, of the enemies and friends of the Stuarts, with the result that, after the fall of James II, the Whigs had held almost uninterrupted power for nearly a century. But the Tories crept back into office under the aegis of George III, consolidated their rule by opposition to the French Revolution, and kept the Whigs in opposition until 1830. The division.. was social as well as political.. they differed considerably in their traditions and in their attitude to the rising middle class. ..' [Russell seems not to explain the persistence of the division]

- 59-63: [Holland House, from Creevey Papers & from Greville. Russell says 'It must not be supposed that all Whig society was as intellectual..' but gives little information of overview type; he just says there was 'an eighteenth-century freedom of morals' with several lovers mentioned, inc. Byron & Sir Francis Burdett & Lady Oxford.

60: Account by Greville of sitting next to Macaulay, without knowing who he was, and noting the conversation: .. self-educated men conceited and arrogant 'from their being ignorant of how much other people know; not having been at public schools, they are uninformed of the course of general education.' [note: remark against industry?].. Alfieri.. Julius Caesar Scaliger.. Scaliger's wound.. Loyola wounded at Pampeluna.. utmost familiarity with every topic.. Primogeniture in this country.. and particularly in ancient Rome.. .

61: '.. Melbourne.. incredibly cultivated. Take this as a sample... 'Allen spoke of the early reformers, the Catharists, and how the early Christians persecuted each other; Melbourne quoted Vigilianus's letter to Jerome, and then asked Allen about the 11th of Henry IV, an Act passed by the Commons against the Church, and referred to the dialogue between the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely at the beginning of Shakespeare's Henry V, which Lord Holland sent for and read, Melbourne knowing it all by heart and prompting all the time.''

- 65-70: [COUNTRY LIFE:]

- 65-66: [Jane Austen & sole interest in religion as a matter for 'livings' in the 'gift' of 'all the richer characters in her books']

- [Ends with Poor Law, Speenhamland scheme etc]

- 71-78 [INDUSTRIAL LIFE. Only two classes; landowners & manufacturers. Latter seem to be only cotton & mines.]

- 71-2: '.. upper classes.. My grandfather, at one period of his life, had for his tutor Dr Cartwright, the inventor of the power loom, which introduced machinery and the factory system into the weaving trade. [Penson, 'Economics..' 96, 1913, dates this invention 1785] .. His reminiscences.. not a word is said about the power loom.. Even so late as 1844, this feeling is amusingly expressed by Kinglake in Eothen, in an imaginary interview between an English traveller and a Turkish Pasha: .. [Note: military use of trains:] 'brigades of artillery are dropped into a mighty chasm called Euston Square, and at the biting of a cartridge, they rise up again in Manchester, or Dublin, or Paris, or Delhi, ..]

PART TWO: THE MARCH OF MIND SECTION B: THE PHILOSOPHICAL RADICALS

- 79-88: [VIII MALTHUS: 3 Pages of this from 'Melincourt' including Common Prayer references]

- 87: '.. If a man's greatness is to be measured by his effect upon human life, few men have been greater than Malthus.'

- 89-100: [IX BENTHAM: Interesting example of Russell weaving a good story from other sources; Works (quite a bit, both personal & notes on 'association principle' & 'greatest happiness principle', on which Russell spends much time), Robert Owen (bit), Francis Place (a lot), Halévy (quite a lot and who emphasizes French pre-revolution thought - and also says Bentham influenced the Indian penal code 28 years after his death, Voltaire, Helvétius - presumably what's in OCEL as 'philosophes' of 'L'Encyclopédie'. Incidentally, his book on Thomas Hodgskin is here, dated 1903; William Thompson seems not to have had a book to himself), Borrow (tiny bit), Hazlitt (large quotation on Bentham's huge fame in France, Spain, Latin America)

2008 note: I can't find anywhere exactly how utilitarianism etc were made into a legal code, nor how British law was changed, despite this being Bentham's importance. For that matter the Code Napoleon is unindexed and I think unmentioned]

- 89: .. sixty years old when he was converted to the principle of democracy.. Rich father/ 'great pains with Jeremy's education'/ 'He fell in love.. his father.. objected because she was not rich. Jeremy gave her up rather than devote himself to money-making, but he suffered severely.. unbelievably shy.. I think, the abiding influence of his conflicts with his father and his renunciation of emotional happiness.'

- 92: .. He read Helvetius in 1769 and immediately determined to devote his life to the principles of legislation. ..

When he came to know Beccaria On Crimes and Punishments, he thought even more highly of him than Helvetius:

'Oh, my master.. you who speak reason about laws, when in France there was spoken only jargon: a jargon, however, which was reason itself as compared with the English jargon; .. so many useful excursions into the path of utility, .'

- 99-100: [Mandeville:] '.. (so all economists of that period contended) .. as a general rule, a man can best further the general interest by pursuing his own. This doctrine, which afforded the theoretical justification for laissez faire, arose, like some other very sober doctrines, out of a jeu d'esprit. Mandeville.. 1723, developed, not too solemnly, the doctrine of 'private vices, public benefits' in which he maintained that it is by our selfishness that we promote the good of the community. Economists and moralists appropriated this doctrine, while explaining that Mandeville should not have spoken of 'private vices', since egoism could only be accounted a vice by those who had failed to grasp the true principles of psychology. Thus the doctrine of the natural harmony of interests.. came to be adopted.. We shall see.. how Ricardo unwittingly gave it its death-blow, and laid the foundations [Note: Russell occasionally includes these rather sad metaphors; a 'bulwark' against Russia, early in this book, is another] for the opposite doctrine of the class war. ..'

- 101-109: [X JAMES MILL:]

- 101: [Background included Scottish patron, 'struck by the boy's abilities', apparently to become a minister [presumably Scotch], journalism with anti-Jacobin, and support for ten years by Bentham, who lent him a house & later a subsidised house, until his history of India was published in 1818, [Russell says I think nothing about this work, though it took as long as his own PM] & '..employed by the East India Company throughout the remainder of his life.'

- 101: [Influences on Mill: Radical, though before Bentham; Hartley; Malthus and Ricardo; and 'Like all his kind, he greatly admired Helvetius, from whom he accepted the current doctrine of the omnipotence of education. ..'

- 102: [J S Mill's autobiography 'one of the most interesting books ever written']

102-3: J S Mill's education, the account from 3 to 14 taken I suppose from his autobiography; Russell seems to believe everything he says; I'm a bit more sceptical of the claims 102: 'one of my greatest amusements was experimental science; in the theoretical, however, not the practical sense..'

- 105: '.. Unselfish and stoical devotion to the doctrine that every man seeks only his own pleasure is a curious psychological paradox. Something not dissimilar was to be found in Lenin and his most sincere followers. ..'

- 106: '.. When various conclusions are, with their evidence, presented with equal care and with equal skill, there is a moral certainty [sic], ... that the greater number will judge right, and that the greatest force of evidence.. will produce the greatest impression.' There is a happy innocency about this confession of faith; it belongs to the age before Freud and before the growth of the art of propaganda. Oddly enough, in Mill's day his confidence was justified by the event. .. in almost all important respects, the course of British politics down to 1874 was such as they advocated. .. in our more lunatic period, it reads like the myth of a Golden Age.'

- 108: [What J Mill did:] '.. brought together Bentham and Malthus and Ricardo and the lower-middle-class Radicalism of Francis Place, who, in turn, was closely associated with the upper-class Radicalism of Sir Francis Burdett. The doctrine of Hartley and Helvetius, with such parts of Hume as could be fitted into doctrinaire orthodoxy, gave the intellectual respectability of a philosophical basis to the excitement of the mob in the Westminster elections. [i.e. cf 94 not House of Commons, but Westminster - I think] .. James Mill's function was that of mortar, ..'

109: '.. benevolence supplied the emotional stimulus, but remained in the background, and at no point overpowered reason. He accepted without difficulty opinions according to which much suffering is inevitable; where those opinions were sound, this was a strength, but where they were false, a weakness. ..'

- 110-115 XI RICARDO

- 110 [cf above, Mandeville] '.. His chief work was The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, published in 1817. This book became.. the canon..; it was found that the devil could quote scripture: both Socialists and Single-Taxers derived their proposals from his doctrines. The socialists appealed to his theory of value, the Single-Taxers to his theory of rent. .. by discussing the distribution of wealth among the different classes of society, he incidentally made it clear that different classes may have divergent interests. ...'

- [Two theories only are considered: his theory of rent, & his theory of value.

Rent means landowner-style rent only, ground rent, so it's not at all complete. Russell explains it differentially; marginal land (presumably including remoteness/ travelling costs) yields no revenue to the landlord as the price for its grain only covers the production costs. So the best land's rent is determined by its greater fertility; or something. Let's see: 111 '.. the rent of an acre.. is the amount by which the value of the crop that can be raised.. exceeds the value of the crop that can be raised on an acre of the worst land in cultivation.' There seems circularity here. Similarly: '.. Corn Laws.. If it had been possible to import grain, the worst agricultural land would have gone out of cultivation. Consequently the difference between the best land and the worst that would have remained in cultivation would have diminished, and rents would have fallen. So much was, of course, obvious to the landowners, who controlled Parliament.' [This all seems dubious to me, as the supply would change! Consider case also where all land is about identical..? Also, on ground rent, how is the extra value above the 'worst' land be found?]

'.. further consequences.. If the importation of grain were to occur as a result of abolishing the import duty, the capital now employed on the worst land would flow [sic] into industry, where it would make the exports required to pay for the imported grain. This new employment of capital would necessarily be more profitable than the old, since, if not, it would not pay to import grain instead of producing it at home. There would.. be an increase of the national wealth accompanied by a fall in rents; there would be more to divide, and.. an increased proportion would go to the industrious classes. This perfectly sound argument naturally appealed to manufacturers, but not to landowners. It was only after the Reform Bill had transferred political power to the middle class that free-traders could obtain control of Parliament. When, in 1846, free trade in corn was introduced, its consequences were found to be such as the economists had predicted. ..'

- 112: [Ricardo could have been more radical; industrious rich however weren't revolutionaries, and distrusted the State 'owing, no doubt, to the fact they did not control it.'

Henry George & single tax was 'perfectly logical' - private ownership of land abolished, all rent to the State. 'This inference.. was not.. even considered by Ricardo']

- 112: [Now, Ricardo's theory of value, which Russell says 'Ricardo answered: They will have the same value if the same amount of labour has been required to produce them.'

'.. In certain cases, Ricardo's theory is quite right, while in certain others it is quite wrong; in the commonest kind of case, it is more or less right, but not wholly. [Russell accepts money 'worth' as identically equal to value; his examples include a bushel of wheat from good vs poor land, which takes he says less labour; and a gold nugget picked up by accident; & over the page a picture by Leonardo, where 'the supply cannot be increased'].

[Russell thinks the only other factor in value apart from labour is the amount of competition; he seems to assume raw materials with competition are indefinitely available & indefinitely cheap:]

113-4: 'Let us take some instance in which, apart from the rent of land, monopoly plays almost no part - say the manufacture of cotton cloth as it was in Ricardo's day. .. There were many manufacturers, all keenly competing.. [sic; not in India etc!]; the raw material was produced under fairly uniform conditions, and sold by the growers competitively. The labour involved in making the necessary machinery was, of course, part of the labour involved in making the cloth; here, also, there was.. plentiful.. iron ore, belonging to many mines which were in no way combined, and.. many firms making textile machinery. .. Royalties to inventors formed, however, a very small part of the cost of a given piece of cotton cloth. On the whole, the price would be determined pretty accurately by the amount of labour involved in making it. [Note that Russell ignores demand; consider e.g. fashions]

...

Where there is monopoly with power to increase supply, the producer has to consider [production].. .. the more he charges the less he will sell, and.. there is some price which gives him the maximum profit. But this has nothing to do with cost of production, except that cost of production sets a minimum..' [i.e. for financially closed-off company]

- 116-124: XII THE BENTHAMITE DOCTRINE

117: 'Politically, the creed.. contained three main articles: laisser faire, democracy, and education. Laisser faire, as a principle, was invented in France during the ancien régime, but it disappeared during the Revolution, and Napoleon had no use for it. In the England of 1815, however,the same conditions existed which had produced it in the France of Louis XVI: an energetic and intelligent middle class politically controlled by a stupid government. ..'..'

124: 'Utilitarianism' because e.g. of the Court of Chancery.. 'Bentham applied this test to all the old lumber of English law, preserved only to provide income for lawyers. .'

[Just a few or many examples. Russell, writing on 'democracy', fascinates me. He uses no general analytical method, but rather has a long-fixed store of arguments on each topic, to be deployed with his literary skill. Classes, industry, rural and town groups, quakers, churches, Cromwell, socialism, Chartists, aristocrats, the poor, educational approaches appear and vanish. Huge events scarcely appear: the US Civil War, the devastating 30 years war, the opium trade in China, and the East India Companies are noted, but no lessons are drawn.

Russell seems to have had no conception of the ways democracy might be controllable: The Times was first printed in 1814 by cylinder presses; by 1900, linotype machines (and typewriters) were in production. Cheap pulp paper dates from 1840s-1900. By age 30, Russell would have been aware of these things, and have formed views on the owners and writers. When he wrote this book, aged about 60, the BBC had only existed for about ten years. It is asking a lot that he might have been aware of their immense possibilities for evil. I'm drawing attention to the link between cheap newspapers and the move to 'democracy', just as I've mentioned the link between the abolition of slavery.

And note that Russell was never aware of Jewish ambitions. Everything Jews wanted censored—possibly excepting the Vietnam War—was ignored by Russell. He never suspects that central banks are important, or that movements have been funded, often hugely, by Jews. Or that American democracy was a sham right from the start. He does quote Doubleday, the Chartist, on loss of wealth in England, after the civil war. That's about it.]

- 125-131: XIII DEMOCRACY IN ENGLAND: Up to votes for rural labourers in 1885

- 126: Universal suffrage up to Henry VI mid-reign, lost in civil wars - though accuracy is open to doubt; example of appeal to the past. [Russell for some reason implies such appeals are Golden Age things, and compares Wat Tyler's rebellion & return to Adam and Eve - surely John Ball? But if true, the argument seems reasonable enough.

- 132-151: [XIV FREE TRADE. Interesting chapter but lacking Chomskyan point about forcing agreement on poor countries (Note: censorship: & with little on raw materials - this topic perhaps partly censored?)

Final pages look at Adam Smith, List, Rockefeller, Darwin, Smiles, Spencer.

COBDEN an example a member of a group in the right [i.e. benefiting people generally] on one issue (& therefore able to be convincing) but who's dropped when he attempts to carry out full beliefs (notably internationalism).

COBDEN DISAPPOINTMENT with Middle Class jingoism..]

- 134-136: Crimean War & long poem by Tennyson, against Bright & I suppose Cobden, cp by Russell to madness over First World War. Continuing dispute which 'idealists' unfortunately have 'on the whole, won the day.'

- 137: [Radical but mainstream writers e.g. in particular Cobbett (and Bright), and their influence (and Cobbett's disappointment when middle classes became imperialistic)]

- 140-1: [Control by ignorant landowners; example of railroad in Britain 'unsuccessful' as apparently typically because the route may have been visible from 'Lady Hastings' place']

- 141: 'Of the corruption in American business and politics, Cobden seems to gave been unaware, although it had existed ever since Washington's first Presidency. ..'

- 143-4: [Clapham's Economic History book quoted spanning 1810 to 1890 in Britain from which Russell concludes 'the importance of Cobden in raising wages can hardly be denied.']

- 147: Popularity in Spain, Italy, Germany of Cobden, and less so elsewhere (and not with Treitschke)

- 148: 'The principle.. failed to take account of certain laws of social dynamics. In the first place, competition tends to issue in somebody's victory, with the result that it ceases... In the second place, there is a tendency for the competition between individuals to be replaced by competition between groups, since a number of individuals can increase their chances of victory by combination. .. two important examples, trade unionism and economic nationalism. .. Both in America and Germany, it was obvious to industrialists that they could increase their wealth by combining to extract favours from the State; they thus competed as a national group [sic] against national groups in other countries. ...'

One of their secrets was to fund both sides in wars, and recover loans from both sides. So there was a net transfer to Jews, plus destruction in both war parties. But if this becomes widely known, other power groups may make their own plans. Personally, I hope so. But of course Marx, as a rich Jew familiar with Jewish money power in the Rothschild era, avoided this prediction!

Section C: Socialism

[XVII MARX AND ENGELS:]

- 183: '.. age of nineteen.. he had written three volumes of poems [sic] to his Jenny, translated large parts of Tacitus and Ovid, and two books on the Pandects, written a work of three hundred pages on the philosophy of law, perceived that it was worthless, written a play, and 'while out of sorts, got to know Hegel from beginning to end,' [NB: Hegel died in 1831, c 6 years before this letter to his father] besides reading innumerable books on the most diverse subjects.' [NB: Seems to be a clash here with another of Russell's judgements on Marx, where he says in effect he was abundantly qualified in ignorance]

- 183: 'Hegel had died in 1831.. influence in Germany was still very great. But his school had broken into two sects, the Old and Young Hegelians, and in 1839 his system was destructively criticized by Feuerbach, who reverted from Hegel's Absolute Idealism to a form of materialism, .. Young Hegelians were distinguished from old by their radicalism. In academic Germany, especially among the young, it was a time of very intense intellectual activity. While Germany, from the standpoint of learning, was ahead of the rest of the world, it was politically and economically far behind England. The censorship was preposterous, and the middle classes had no political power. [Struwwelpeter and, I suspect, Max und Moritz belong to this period] It resulted inevitably that the intelligent young were radical if not revolutionary, and that they were very open to political ideas coming from abroad, especially from France. Marx in his youth was not isolated, but was one of a group of eager young men, ..'

- 184: 'Marx first sought a career in journalism. In 1842 he became a contributor, and soon afterwards the editor, of the Rheinische Zeitung, and now he first became aware of problems for which nothing in academic philosophy offered any solution. The first .. that came to his attention was the question of a law for the imprisonment of the poor for stealing wood from the forest. He realized that economic questions had been unduly neglected.. When .. [it] was suppressed by the censorship in January 1843, Marx.. decided to become acquainted with Socialism.'

- 184: '.. Socialism at the time [1843] was predominantly French. English Socialism, under the leadership of Robert Owen, had become mainly secularist and anti-Christian. Owen.. had always been opposed to political methods, and radical politics in England was left to the Chartists, whose programme did not directly concern itself with economic questions. In France.. the movement inaugurated by Saint Simon and Fourier had continued and was full of vigour. Marx made the acquaintance of the leaders, of whom the most important were Proudhon and Louis Blanc. .. It must be said that Socialism before Marx was not worthy of any great degree of intellectual respect. ..'

[Footnote from A J P Taylor: 'Proudhon (1809-65) coined two immortal phrases: 'Property is theft' & 'universal suffrage is counter-revolution.' He advocated co-operative societies instead of political revolution and put his faith in Napoleon III. His followers gave Marx trouble during the 1st International.' Saint-Simon and Fourier described socialist utopias. Robert Owen preached cooperation & ran a cotton mill on idealistic lines. His followers founded Utopian colonies in the U.S. In old age he became a spiritualist.']

- 185: 'The belief in an intimate relation between philosophy and politics.. remained part of his [Marx's] creed. 'Philosophy.. cannot be realized without the uprising of the proletariat; and the proletariat cannot rise without the realization of philosophy.' To English-speaking people, who do not take philosophy seriously, this must seem an odd sentiment, unless they have learnt to accept the Communist creed.'

- 185: 'His friendship with Engels began.. in Paris, in.. 1844. Engels was two years younger than Marx, and had been subjected to the same intellectual influences in his university years. But his father was a cotton spinner with factories both in Germany and in Manchester [sic], and Engels had been sent to Manchester to work in the family business. This had given him first-hand knowledge of up-to-date industrialism... He was at this time writing his book on the condition of the English working class. This book uses powerfully the same kind of material that Marx afterwards used in the first volume of Capital. .. It makes it possible to judge of the importance to be attached to Engels in the joint work of the two men. Marx had been, .. too academic. .. Engels invariably minimized his share in all that the two men did together, but undoubtedly it was very great. ..'

- 186: 'Engels.. [had been] converted [to communism] by a man named Moses Hess, who was prominent among the German radicals. ..'

- 186: '.. Marx made friends with Heine, who much admired him and became a Communist. The Continental intellectuals of that day were far more advanced politically than those in England, no doubt because the middle classes had less power, and because revolution was the obvious first step in progress. .'

- 186: 'In January 1845, at the request of the Prussian Government, Marx was expelled from Paris, and therefore went to Brussels. .. conducted Communist propaganda.. various bodies such as the Workers' Educational Society [sic; surely 'Association'?], .. The Federation of the Just, which met in Great Windmill Street in London, developed into the Communist League, which included in its programme, 'the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the dominion of the proletariat, the abolition of a class society, and the introduction of an economic and social order without private property and without classes.' In December 1847, this body decided that Marx and Engels should draw up a statement of its aims. The whole importance of the Communist League.. is due to this decision, since its outcome was the Communist Manifesto.

[Note on proletariat who must have been regarded as unimpressive 'goyim' types by Jews; probably thuggish and stupid, low forms of life. The post-1945 policy by Jews of helping immigration invasions into white countries can be regarded as a similar idea, of Jews supposedly liking and helping proletariats. Of course neither case has been successful.]

The Jewish rabbinical view, embodied in the Kahal system, is that what's theirs is mine, and what's yours will be mine, after the Kahal has done its work.

A 'bourgeois' is a person or group who is non-Jewish and owns money or assets. The ownership is viewed by Jews as shocking and temporary and up for spoliation.

Jews during both world wars regarded many goyim—small businessmen, some soldiers and sailors, teachers, medicos, flight and engineering people etc as bourgeois or petit bourgeois. In Russia, peasants were not regarded as bourgeois; they didn't own disposable assets. No doubt there were fine distinctions varying with situations—rich or poor women, clerks, musicians, salesmen. There must have been many a discussion on things like inheritance and death 'duties', income tax, property prices. Imagine the salivating rabbis!]

I do not know of any document of equal propagandist force. And this force is derived from intense passion intellectually clothed as inexorable exposition.

It was the Communist Manifesto that gave Marx his position in the Socialist movement, and he would have deserved it even if he had never written Das Kapital. ..'

- 187: 'Few movements in history have disappointed all participants more completely than the revolutions of 1848. ..'

- 188: 'Marx's life is sharply divided into two periods by the failure of the 1848 revolutions, which deprived him of immediate hopefulness and turned him into an impoverished exile. ...'

- 189: [Letter published in New Statesman & Nation 1933, from Marx to his daughter. (Another Russell book, 'Religion and Science', quotes from a magazine - in that case, the Listener.)]

[XVIII DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM:]

- 196: [Russell states in advance that he intends to prove (1) Materialism.. may be true, though it cannot be known to be so; (2) .. elements of dialectic .. from Hegel made him regard history as a more rational process than it has in fact been, convincing him that all changes must be in some sense progressive, and giving him a feeling of certainty in regard to the future... (3) .. but for the influence of Hegel it would never have occurred to him that a matter so purely empirical [i.e. as economic development] could depend upon abstract metaphysics; (4) .. economic interpretation of history, .. seems to me very largely true, and a most important contribution to sociology; I cannot.. regard it as wholly true, or feel any confidence that all great historical changes can be viewed as developments.' (i.e. I think he means in the sense of contributing to 'progress')]

- 198: 'The philosophy advocated in the earlier part [of Eleven Theses on Feuerbach, 1945] is that which has since become familiar to the philosophical world through the writings of Dr Dewey, under the name of pragmatism or instrumentalism. .. their opinions as to the metaphysical status of matter are virtually identical. ..

The conception of 'matter', in old-fashioned materialism, was bound up with the conception of 'sensation.' Matter was regarded as the cause of sensation, and originally also as its object... Sensation was regarded as something in which a man is passive, and merely receives sensations from the outside world. This conception.. is .. so the instrumentalists contend - an unreal abstraction.. Watch an animal receiving impressions.. its nostrils dilate, its ears twitch, its eyes are directed.., its muscles become taut.. All this is action, mainly to improve the informative quality of impressions, partly such as to leas to fresh action.. And as a cat with a mouse, so is a textile manufacturer with a bale of cotton. The bale .. is an opportunity for action, it is something to be transformed. The machinery by which it is to be transformed is explicitly and obviously a product of human activity. Roughly speaking, all matter, according to Marx, is to be thought of as we naturally think of machinery: it has a raw material giving opportunity for action, but in its completed form it is a human product.

Philosophy has taken over from the Greeks a conception of passive contemplation.. Marx maintains that we are always active.. we are never merely apprehending our environment, but always at the same time altering it. ..

I think it may be doubted whether Engels quite understood Marx's views on the nature of matter and on the pragmatic nature of truth; ..'

XIX The Theory of Surplus Value

XX THE POLITICS OF MARXISM:

- 226: 'Marx's doctrine of the class war was one of the forces that killed 19 C liberalism in Europe, by frightening the middle classes into reaction, and by teaching that political opinions are, and always must be, based upon economic bias rather than any consideration of the general good. In America.. old fashioned liberalism./. but..

.. there are four points in his theory .. of such importance as to prove him a man of supreme intelligence.

The first is the concentration of capital, passing gradually from free competition to monopoly.

The second is economic motivation in politics, which now is taken almost for granted, but was, when he propounded it, a daring innovation.

The third was the necessity for the conquest of power by those who are not possessed of capital. This follows from economic motivation, and is to be contrasted with Owen's appeal to benevolence.

The fourth is the necessity of acquisition by the State of all the means of production, with the consequence that Socialism must, from its inception, embrace a whole nation, if not the whole world. Marx's predecessors aimed at small communities.. but he perceived the futility of all such attempts.'

PART THREE: DEMOCRACY AND PLUTOCRACY IN AMERICA Section B: Competition and Monopoly in America

- 99 ff: [Note: Russell's Jew-free Character sketch of Rockefeller, b 1839] 'John, a careful, serious, shy boy, loved his mother and imbibed her virtues. He became deeply religious, a teetotaller, and a non-smoker; he never used profane language.. It may be doubted whether, in all his ninety-five years, he has ever done anything that would have been disapproved of in his Sunday school..'

PART 2: NATIONALISM AND IMPERIALISM | VIII The Principle of Nationality | IX BISMARCK AND GERMAN UNITY

- 153: 'Liberalism and the principle of nationality suffered joint defeat in 1848, but soon revived. In Italy, in 1859 and 1860, they won, in alliance, a spectacular victory in the unification of almost the whole country, with parliamentary government under the constitutional rule of Victor Emmanuel. (Venetia was won in 1866, and Rome in 1870.)

A similar liberal-nationalistic development was to be expected in Germany, where the victory of reaction after 1848 did not seem likely to be permanent. But the course of events in Germany was not according to the preconceived pattern. The principle of legitimacy, a hampering legacy of the Congress of Vienna, was thrown over by the Conservative Government of Prussia, which found satisfaction for German nationalism with only a few concessions to Liberalism. The separation of nationalism from liberalism, and of conservatism from the principle of legitimacy, was an important achievement, which profoundly affected European development. It was mainly due to the personal influence of Bismarck, who, on this account, must be reckoned one of the most influential men of the 19th century. ..'

- 164: 'Bismarck had no respect for the principle of legitimacy. He stood simply for Prussian interests, and was quite willing to make friends with Napoleon III, 'the man of sin' as Conservatives called him, if that would help him to make Prussia great. Writing to his arch-Conservative friend and former patron Gerlach, in 1857, he says:

[Note: revolutionary power:] How many entities are there left in the political world to-day that have not their roots in revolutionary soil? Take Spain, Portugal, Brazil, all the American Republics, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Greece, Sweden, and England, the latter with her foot even to-day consciously planted on the glorious revolution of 1688. Even for that territory which the German princes .. have won partly from Emperor and Empire, partly from their peers the barons, and partly from the estates of their own country, no perfectly legitimate title of possession can be shown, ...

... Unlike the upholders of legitimacy. He had no international principle. How the French chose to be governed was no concern of his; whether they had a Bourbon, a Bonaparte, or a Republic.. were.. not questions that concerned a patriotic Prussian, except in so far as they affected France's power for mischief. In this he differed from Conservatives and Liberals alike, but he taught the world to adopt his principles. Following his precepts, the Tsar, at a later date, was not afraid to ally himself with the atheistical republican government of France.

.. For war with France, the ground had to be carefully prepared. The military preparations could be safely left to Moltke; for although the two men often wrangled, Bismarck took care that his diplomacy should only produce wars that Moltke felt confident of winning. With the help of the military alliances with South German States, and after the experience of two wars, Moltke was ready to promise victory if he was allowed two or three years of preparation. The other problems were diplomatic. It was necessary to ensure the neutrality of the other Great Powers. Russia was secured by the promise to support revision of the Treaty of 1856 as regards the closing of the Straits. England might have sympathized with her ally of the Crimean War, but Napoleon was tricked by Bismarck into an expression, in writing, of the desire to annex Belgium, which, published at the crucial moment, effectively prevented English assistance to France. Austria and Italy remained doubtful to the end, and were only converted to the German cause by Napoleon's military misfortunes. Italy would have sided with France if the Emperor had consented to Victor Emmanuel's occupation of Rome, but he refused, under the influence of Eugénie's ultramontane fanaticism. This it was left to Luther's countrymen, at Sedan, to end the temporal sovereignty of the Pope.

The final stages leading up to the rupture with France were managed by Bismarck with consummate skill. .. one was as clever as the other was silly, and the clever rogue made the other's roguery apparent to all Europe, while successfully concealing his own. ..

The war, as every one knows, resulted, for Germany, in the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine and the formation of the Empire; for France, in the payment of a huge indemnity, the establishment of the Third Republic, and the Paris Commune - extirpated with inconceivable barbarity by the new government of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.

The Empire, which embraced all Germany except German Austria, had a federal constitution very similar to that of the North German Federation established in 1867. The King of Prussia was German Emperor, the Prime Minister of Prussia was Imperial Chancellor; he and the other ministers were responsible to the Emperor alone, not to Parliament. There was a Federal Diet (Bundesrat), consisting of delegations appointed by the several States; and there was a Parliament (Reichstag) directly elected by manhood suffrage. The Reichstag had control of finance, and laws required its assent, but the initiative in legislation belonged to the Bundesrat. Bismarck was Chancellor until 1890, and in practice the constitution scarcely limited his omnipotence. The middle classes had been tamed, ...

His achievement in the years 1862 to 1871 is perhaps the most remarkable feat of skill in the history of statesmanship. He had to manage the King, whose wife and son and daughter-in-law were all bitterly hostile. He had to convert the nation, which at first hated him and his policies. He had to make Nationalism Conservative instead of Liberal, militaristic instead of humanitarian, monarchical instead of democratic. He had to secure the victory of Prussia against the Danes, the Austrians, and the French, in spite of the fact that none of the other powers wished him to succeed. He could not allow the King to understand his policy, because it was not such as an honest old soldier would approve. He could not let the world understand it, because the world would have defeated it if it had understood it. At every moment he was liable to grave disaster. .. there was not in any country another statesman who understood the diplomatic game as he did. Even Disraeli, as subsequently appeared, was a child in his hands. ..'

- 218-220: [Character of Holstein, including resignation threats and homosexual blackmail. The Kaiser only succeeded in meeting him once.. The Kaiser, after his fall, said that the dismissal of Bismarck was like rolling away a granite block and revealing the vermin underneath. .. From 1890, when Bismarck fell, till 1906, German foreign policy was Holstein's. He advised the rejection of Chamberlain's offer of alliance; he inspired the Morocco policy which Bülow forced upon the unwilling Kaiser. He did not recommend the Kruger telegram, which was the Kaiser's own doing, but foresaw that the responsibility would fall upon the Foreign Secretary, Marschall, whom he wished out of the way... his twisted hatreds did much to bring about the atmosphere of war..'