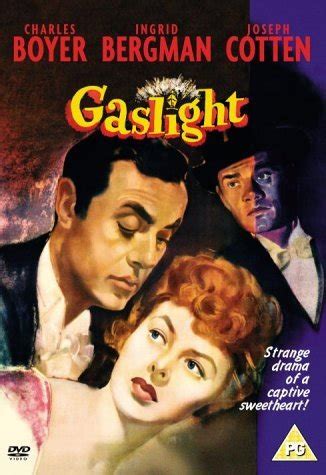

Gaslight. 1944 film. Review by Rae West.

Garish poster. Black and white. Set in 1875. 'Gaslighting' is not quite as usually believed.

I'm writing here of the 1944 version. Hard to believe that almost the same Jews who arranged all this would also successfully arrange massive slaughters in many parts of the world. It has the usual slightly quavery music, no doubt caused by the soundtrack being encoded in the film itself. At least lip synch worked.

Charles Boyer was the joint lead. I admit to being fascinated by his right ear's extreme convolutions.

Ingrid Bergman was rather inconsistently shown being fainting and feeble, but shouting back loudly later. She went to an asylum to observe an inmate and adopted her furtive eye movements. Or so says Angela Lansbury; I suspect she watched the 'English' version.

Lansbury (I only recognised her after) was good as a cockney maid. She dallied a bit with a policeman, though 'below stairs' didn't seem to exist in the house in Thornton Square.

Joseph Cotten was the Scotland Yard detective; the scene of his workplace was a small office all arranged in front of the camera to obviate the need for doors.

We also had Dame Whitty, a ancestor of one of the COVID fraudsters.

The scene-setting intro shows a shyish girl, daughter of a famous opera singer, victim of her unsolved murder. She's by Lake Como, being tutored by a music teacher who looks a bit like Bertie Russell. The long-haired musician detects that Ingrid B is not as enamoured of music as her ma was. And she is implausibly in love with someone she's known for two weeks. Her paramour suggests moving to London.

Another actor, in effect, is the house in Thornton Square in which the musical ma met her death. The sets of the house and the square aren't realistic: the front door opens straight into the main room. There are dramatic banisters (handrails) usually lit from below. And interior decor resembling heavily-patterned Victorian style, with grafts of carved wooden turrets and machicolations (I think).

Plus a rooflight that looks as though it would leak rain.

The outdoor sequences are laughably empty, though occasionally there's a horsedrawn equipage which is too big for a cab, accompanied by coconut shells.

I'd thought gaslighting was a deliberate tinkering with gas, to worry the victim, but in fact if was a side-effect of Boyer in the roof space—or rather, attic room—who turned on gaslight when rummaging about. The driving mad was accusations of mislaying or forgetting objects, and being said to be too ill to get out.

Gaslight in fact used gas mantles, fragile things made my soaking a frame wrapped in cloth in a solution of some 'rare earth' element, to leave a cylinder; when heated, it glowed. High tech in 1875, but forgotten by 1940. Even matches were subject to technical change; the 'match girl' strike was in 1888.

The black and white rendition must have taken some effort to achieve, either in the original or in the blu-ray version. I hadn't quite appreciated how all the objects had to be distinguished by tone, so they didn't merge into each other.

The film—not yet a 'movie' of course—had a theme of desire for jewels. There's a scene supposedly at the Tower of London of the Crown Jewels. Not for the first time I wondered if this was a nod to Jews interested in these unimpressive minerals.

Gaslight. 1940 film in Britain.

The British—or Jewish—version of 1940 inherited a stage tradition. I'd guess a lot of material in the book was included in this film, and pruned away by American Jews. I can imagine the producers saying Gee, Moshe, we just doh need this crap."There are far more extras than the Boyer-Bergman version. There are crowds of children, for example, and a local toyshop, and punch-and-judy show, and a snack place: I don't even know what it would have been called. There's a music hall scene, quite interesting as showing the poor man's opera. This included a can-can from Paris; which seems a bit over the top. The credits n the version I saw credited a ballet company, but said nothing else.

This film started with a rather long scene-set plus murder scene, replaced with tuition in Italy in the US version. In it, all the names are changed, and the location, Pimlico here. The US version also relates the wife to the victim, and gives them a common musical thread, which includes Boyer as pianist. I'd guess the British version is more faithful to the book; which shows the advantages of dramatic reconstruction.

The helpfully inquisitive local works in a carriage place, the ancestor of the modern garage, which itself may be superseded by an electrical version. The man sens his time grooming an obviousy model horse while talking to his cheery young assistant. Cotten's promotion to detective gives the US version a slight problem: why should he send his time on just one case?

The British film is more unpleasant than its transatlantic offshoot. The maid and the master kiss and they even do out. The marriage is revealed to be fake—He's a bigamist, with a wife in Australia. Walbrook says he hates her, and says things like "You're going me and you'll die raving in a asylum." It's a bit unnecessarily specific: the hidden jewels are specifically rubies, "worth 20,000 pounds."

© Rae West written & uploaded 23 May 2023.