The Age of Reason

by Tom Paine

Revisionist review (of Paine and others) by Raeto West 5 March 2024

Much of my review looks at Chapman Cohen, who was probably just another urban scribbling Jewish immigrant into England. I'll assume he was rather stupid, like most Jews, a fanatical adherent to rubbish he learned from his mother, from his father, and from his circumambient 'education'. His entire outlook must have been shaped by the need to lie. His 40-page introduction is written in the 'artificial intelligence' style of his day, with Jewish emotions attached to such events as the 'French' Revolution, the English 'Restoration' of the monarchy, and the Bible in English.

Cohen, like an AI search engine, seeks out aspects of Paine and supplies automated emotion-only standard phrases. He's very helpful in highlighting Paine's intentions, as I found pushing through his words.

Paine (and/or writers under his name) seems to have looked into political theory, mostly of democracy, and religious theory, mostly belief in 'God'. Both had secret long-term Jewish objects, notably–

• 'Democracy' which in practice resembled modern disruptions by rented mobs of the 'Soviet' type, paid or controlled by Jews and with no genuine concern for ordinary people, however useful or good. This understanding has been suppressed at least since 1900; before this there was widespread dislike of the idea of democracy. Paine's work did not say much about practical democracy; instead, it criticised and attacked all established people, resembling Marxism in supposedly supporting the 'proletariat' and avoiding discussion of practice. The avoidance of discussion about the proposed new conditions was essential, since few people wanted rule by obsessive Jewish fanatics.

• 'God' was a Jewish concept, a euphemism for 'Jews' as a group, with emphasis on 'rabbis'. This 'God' was part of the Jewish mentality, deeply embedded and perhaps instinctive. Paine's Age of Reason took the Jewish view that belief in 'God' was rational, itself an irrational idea, but which was repeated so much and over so long a time that people generally have been paralysed mentally into acceptance.

Religions with paid-up officials, hierarchies and buildings, group payments, collective sense, have an economic momentum which may build into a self-replicating structure taking up a high proportion of spare capacity in communities. So they may become self-perpetuating and persecuting groups—on similar lines to Jewish 'Kahals'.

Life after death has implications which have not been noticed generally. If evildoers have life after death, they may be judged, prosecuted, and talked about. This distracts from doing anything about their beneficiaries. [It surprised me to see Miles Mathis say in 911again.pdf: 'Silverstein ... is still alive, age 92. ... He will meet his maker soon enough, and have to account for everything down to the last farthing...'. Of course he won't. Many people seem unaware they don't have to join a paid club for their beliefs. Life after death points this out]

And there were other issues, such as opposition to the 'Hereditary Principle'. In practice, this opposed inheritance by goyim, but kept completely quiet on inheritance by so-called 'Jews'. In the words of Bertrand Russell, ‘His objection to the hereditary principle, which horrified Burke and Pitt, is now common ground among all politicians’. They clearly were persuaded successfully, just as many of the surviving important English after Cromwell were persuaded.

And Paine and others used repeated assertions to 'blackwash' everyone likely to take different views, giving a rather inevitable repetitive and predictable style to their writings. This is clearer after the lapse of time, just as in modern times recent Jewish propaganda does not age well, picking on one-time enemies of Jews who now seem completely unimportant.

Propaganda includes enticements, and we find Paine recommended such things as old-age pensions, graduated income tax, and death duties. It's an amazing comment on British historians that H A L (Herbert Albert Laurens) Fisher's History of Europe (published mid-Great War, 1916) attributes such things as general education and pensions to Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto, not to Paine.

Jewish censorship of wars, bank frauds, budget frauds, debt build-ups, is as great or probably greater than in Paine's time. Media control by Jews is so strong that there are constant legal threats to people with ideas; and the ways things work are hidden by ever-more hard to understand laws, paper secrets, financial concealment.

The 'Holocaust' fraud is still being pushed on simple goyim as an alternative to Christianity; instead of the tortured 'Jesus' figure, the sacred number of 6 millions Jews is supposed to have been killed horribly. Probably money will be handed out to fanatical priest types in exchange for tithes, land rents, payments to excuse 'sins', and so on. It has to be said whites are so simple or powerless that this may work.

Today, we must consider the USA, Britain, and France as states, each with a powerful, secret, minority of Jews. It's fairly well-known, now, that 1700s France was under attack by Jews, and the 'French' revolution was secretly but powerfully influenced by Jews. It's not so well-known that the Bank 'of England' was Jewish. The collective interest of the Jews in the American states seems to have been to take over the banking system. Discussion of Paine now has to consider his attitude to these issues.

Paper money, in the unlimited 1913 Fed scheme in which debt is hidden within money itself, is presaged by Paine: ‘The [sinking fund] funding system is not money; neither is it, properly speaking, credit. It in effect, creates upon paper the sum which it appears to borrow, and lays on a tax to keep the imaginary capital, alive by the payment of interest, and sends the annuity to market to be sold for paper already in circulation.’

Here is generally asserted material on Thomas Paine (1737-1809). Quaker father, Anglican mother. Family history vague. The claim usually made, that he published large numbers of pamphlets and books, but never made money from them—the source(s) of his income being totally obscured—suggests they were commissioned by him. His early life—a staymaker?—suggests a connection with clothing and trade & may be a crypto-Jew link. A sketch map of the town of Thetford in about 1750 (online source) shows the usual features of prosperous small towns of the time. (With lime kilns, and a gallows).

His reputation as one of the leading democrat theorists must raise doubts: today we are better aware of the mythologies ascribed to 'democracy' than people could have been in the times of royalty, aristocracy, and churches.

Chronology below. Alleged publications in bold. Non-bold text has other relevant things:–

[1712-1778: Rousseau]

[1700-1775: Savery 1698; Newcomen 1712; Boulton and Watt founded 1775. Examples of steam power marking increase in mechanical power over wind power & manpower—relevant to reduction in slavery where it applied]

1737-1809: Thomas Paine

1776 Common Sense published

1776-1783 (15 parts) The American Crisis

1786 Dissertation on the Affairs of the Bank

1791, 1792 (2 parts) Rights of Man

1794, 1795 (2 parts) The Age of Reason

1796 The Decline and Fall of the English System of Finance

1797 Agrarian Justice

1810 Posthumous short work in French on Freemasons

[1812–1815 Unimportant war between USA & Britain—infinitely fewer deaths than the 50-year-later 'Civil War'. Neither war has been analysed with Jewish influence, but probably it resulted in rearrangements suiting the concealed power]

[1827 Sir Walter Scott's nine volumes on The Life of Napoleon. Volume II states that the French Revolution was planned by the Illuminati (Adam Weishaupt) and was financed by the money changers of Europe (The Rothschilds). Sir Walter Scott sums up the situation with these words—“These financiers used the (French) Government as bankrupt prodigals are treated by usurious money-lenders who, feeding the extravagance with one hand, with the other wring out of their ruined fortunes the most unreasonable recompenses for their advances. By a long succession of these ruinous loans, and various rights granted to guarantee them, the whole finances of France were brought to a total confusion”]

[1830 William Cobbett (1763-1835): Main work (arguably; he wrote histories, and on cottages, and founded the precursor of Hansard) Rural Rides, his observations made since 1821 of about ten years' travel, published 1830. Cobbett bemoaned "If I had time, ... I would find out how many of the old gentry have lost their estates, and have been supplanted by the Jews, since Pitt began his reign."]

[1848 Chaotic Republican revolutions and secret opposition]

[1858-1866 Goldwin Smith Regius Professor of Modern History, Oxford. Prolific author. Almost uniquely Jew-aware]

[c. 1908 Moncure Conway (1832-1907) biographer of Paine, apparently published after death. 1976 Encylopaedia Britannica says 'no full-length study of Paine ... replaces Conway's biography'. In 2018, we find J C D Clark's Oxford-published book on Paine, which seems unrevisionist and of little value]

[1912 Hypatia Bonner on Blasphemy Laws. Paine has a few mentions. Crypto-Jewish book on blasphemy. No consideration at all of the vast support for Jewish rubbish, which now, more than a century later, has immense legal force.]

Oil painting of Paine

The dates for Paine (1737-1809) are far earlier than the invention of photography: Daguerrotypes date from 1840s; Fox Talbot's claim to the first chemical process negatives was 1834. So the portraits of him can't be expected to be accurate.

Miles Mathis is the best (and more-or-less only) researcher into genealogical detail, but to date has not written much on Tom Paine. “... let us search on the name Payne. We find Gen. William Payne, 1st Baronet, which doesn't immediately help us with Obama, but which does help us with Franklin. His son married Emily Frankland-Russell, daughter of Robert Frankland-Russell, 7th Baronet. The 6th Baronet was a Frankland, so where did the Russell come from? The peerage.com doesn't tell us. The women of that time were Murrays (Dukes of Atholl), Hamiltons, and Grants, not Russells, but they are all related to Russells. All this links Ben Franklin to Thomas Paine, of course, since that is just a variant spelling.” So it's likely that Paine will show all the red flags of crypto-Jew and Freemasonic ancestry and ideas.

MILES MATHIS on GEORGE WASHINGTON & BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

From wash.pdf. George Washington was one of the richest men in US history, although they don't teach you that in school. I have shown George Washington was from English royalty and crypto-Jewish families. His lineage (and that of his wife) goes right to the top of both the English peerage and the East India Company. So it is very unlikely George was fighting against either one.From ben.pdf. Mathis said Franklin was a British agent. Britain had many power hierarchies, so it's not entirely clear what Mathis means by a ‘British agent’.

Franklin is said to have stated, among other things, that ‘If they are not expelled from the United States by the Constitution within less than one hundred years, they will stream into this country in such numbers that they will rule and destroy us and change our form of Government for which we Americans shed our blood and sacrificed our life, property and personal freedom. If the Jews are not excluded within two hundred years, our children will be working in the field to feed Jews while they remain in the counting houses, gleefully rubbing their hands.’ It's possible such a speech may have been made (as Henry Ford's Dearborn material may have) to seed the idea of hate of Jews into Americans. In Henry Ford's case, after the 'Great War' and before the construction of Hitler.

Here's Miles Mathis: ‘In fact, the encyclopedias try to tell us Franklin's father was a soap maker, and that his grandmother was an indentured servant. They tell us the Folgers were Puritans, “just the sort of rebels destined to transform colonial America.” Given what we have discovered, that already looks like a lie. Franklin's family was from the highest levels of the peerage, as we have seen. And like Samuel Parris of Salem, the Folgers weren't real Puritans: they were crypto-Jews running fantastic projects.

And what this means is that the founding fathers were actually from the highest reaches of the British peerage, closely related to the Monarch and the peers they were allegedly fighting in the American Revolution. Which should make us ask if the American Revolution—like the other wars we have unwound—was managed. We always see the same families on both sides of these fake revolutionary wars, indicating a large manufactured event. I will have to gather more proof as we go, but it already looks to me like the War of Independence was largely faked, with the same families controlling the United States both before and after the alleged Revolution. The US has never been independent from the beginning.

[Ben] Franklin also published Moravian religious books in German at the same time. This is another red flag, as you will see if you go to the page on the Moravian Church. There is nothing in Ben's mainstream bio to explain his connection to the Moravian Church, but what I have shown you above explains it, since the Church is another Jewish front. It was founded in Bohemia by Jan Hus in 1415. [Bertrand Russell on Whitehead: Whatever historical subjects came up he [Whitehead] could always supply some illuminating fact, such, for example, as the connection of Burke's political opinions with his interests in the City, and the relation of the Hussite heresy to the Bohemian silver mines.]

Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII, supposedly of the ancient Wittelsbach dynasty, was the son of a Sobieski from Poland, making him Jewish in several lines. However, in the mid-1700s, the issue hadn't yet been decided on the local level.

At age 25 Ben became a Mason, and just three years later he was a Grand Master. That's 33 levels in 3 years, if you are counting. He edited and published the first Masonic book in the Americas, the Constitutions of the Free-Masons. That confirms my readings of him above: he was an extremely prominent spook from birth, groomed from the cradle to a life of projects.

Franklin's close relationship to all these peers in the two decades leading up to 1776 is all the proof you should need of that.

What if he [Franklin] didn't go to London at age 17, but was already there? He was simply assigned his project then, and was shipped out to Philly to start it up.

AGE OF REASON

BEING

AN INVESTIGATION

OF

TRUE AND FABULOUS THEOLOGY.

By THOMAS PAINE.

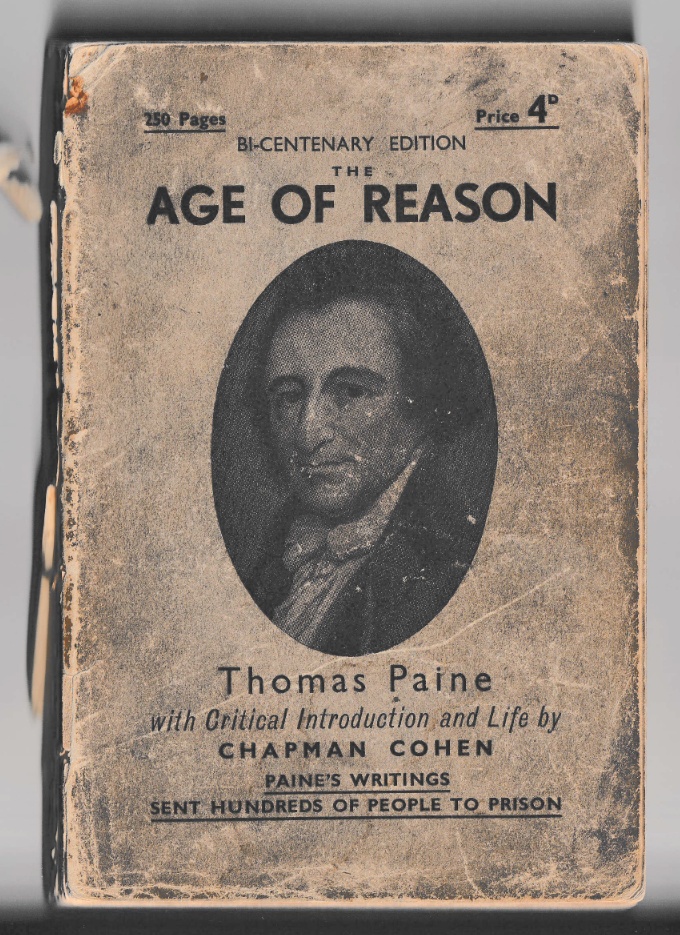

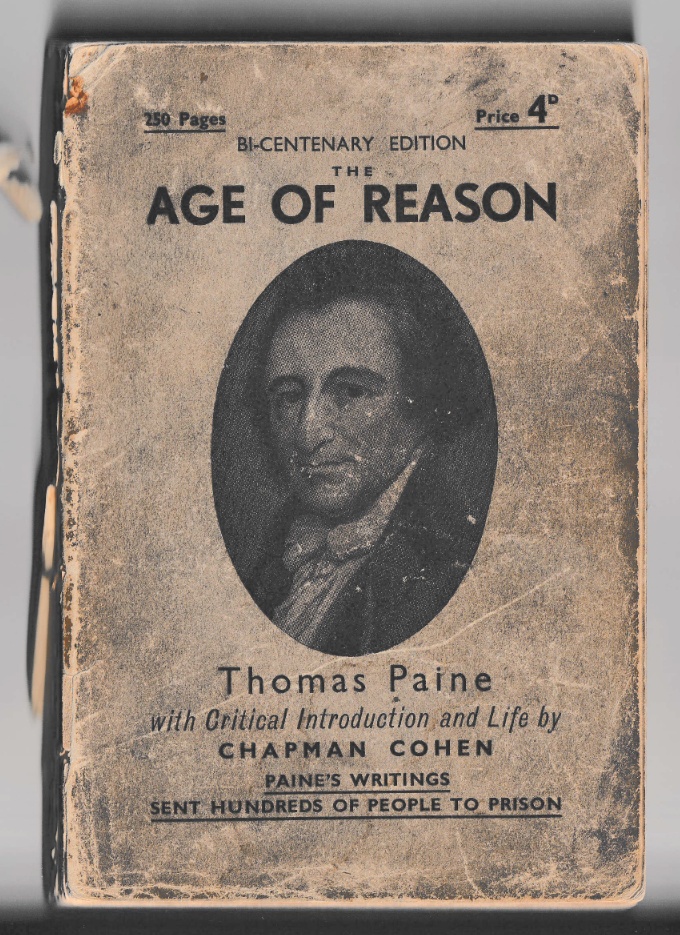

Cover of a 1937 edition. The 'bi-centenary' is of Paine's birth, not publication. There were three publication dates, of three parts; as far as I could find there's no evidence Paine wrote them. He may have financed them while thinking of the legal position. 'Hundreds of people to prison' appears to be true enough, but Cohen doesn't state what the convictions were for; they may have been correct interpretations of the laws of the time. Generally, the Jewish approach to laws is very strictly to consider whether Jews are thought to benefit—or not. Cover of a 1937 edition. The 'bi-centenary' is of Paine's birth, not publication. There were three publication dates, of three parts; as far as I could find there's no evidence Paine wrote them. He may have financed them while thinking of the legal position. 'Hundreds of people to prison' appears to be true enough, but Cohen doesn't state what the convictions were for; they may have been correct interpretations of the laws of the time. Generally, the Jewish approach to laws is very strictly to consider whether Jews are thought to benefit—or not.

The eighteenth century (1700s) as supposedly ruled by reason made its impact on Victorian Britain; "eighteenth century rationalism" was a slogan covering everything from 'deism' and Gibbon's history of Rome to the omission of the East India Co and the Jewish financing of wars and warships. |

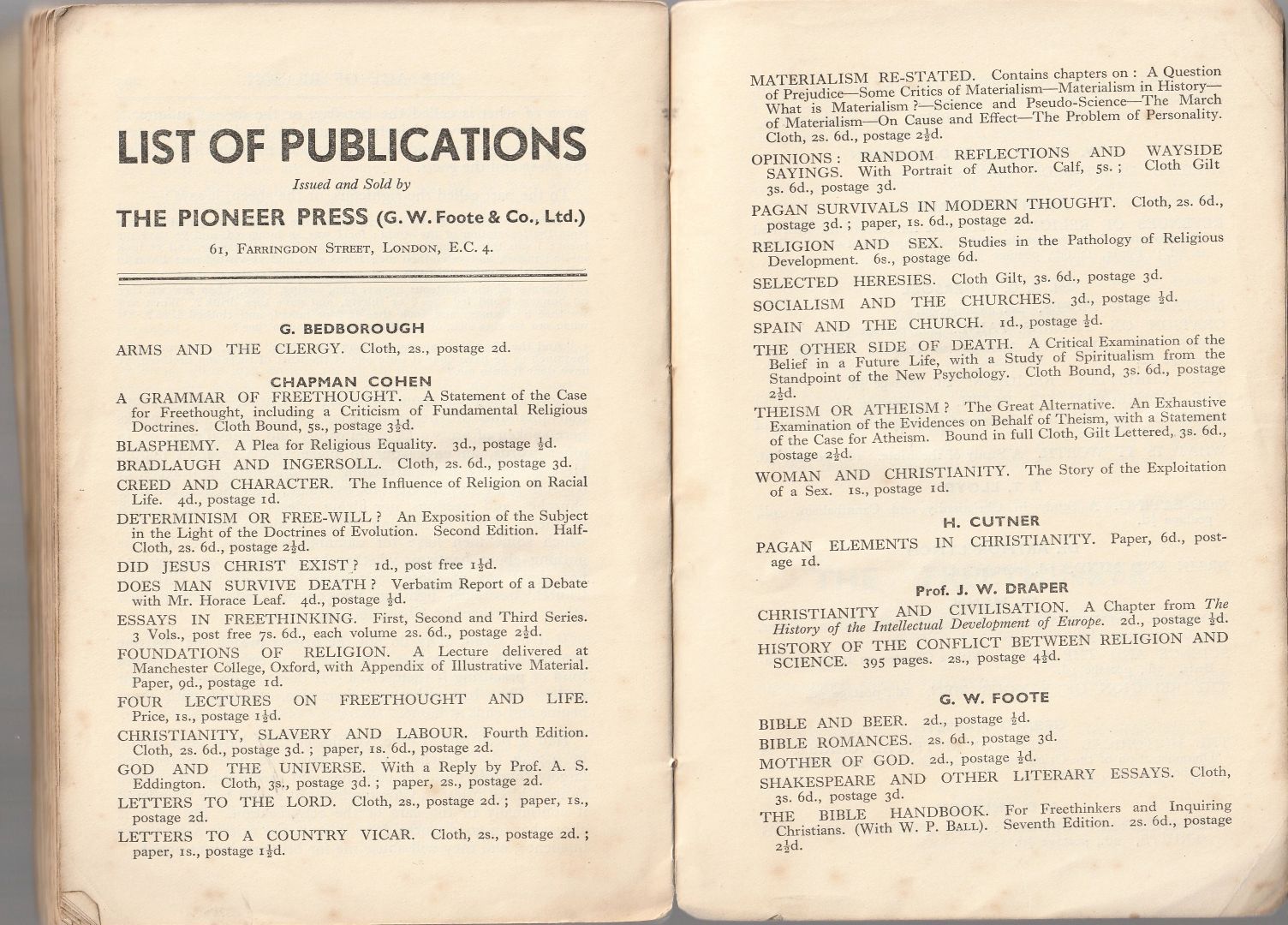

Pioneer Press of 61 Farringdon Street, E.C.4 was G.W.Foote and Co., Ltd. This company also published the weekly "Freethinker" ('Every Thursday, price threepence'). South Place Ethical Society in Red Lion Square was associated with them. All these outfits were Jewish and took a distinctly Jewish attitude, for example claiming that there was rational religion, without ever specifying what it was, and never mentioning Jews. Pioneer Press of 61 Farringdon Street, E.C.4 was G.W.Foote and Co., Ltd. This company also published the weekly "Freethinker" ('Every Thursday, price threepence'). South Place Ethical Society in Red Lion Square was associated with them. All these outfits were Jewish and took a distinctly Jewish attitude, for example claiming that there was rational religion, without ever specifying what it was, and never mentioning Jews.

Quite a remarkable strategy, on the face of it needing tremendous and unyielding self-discipline, though in practice isolation from the host community and the use of Synagogues as a refuge made the secrecy less intolerable. 19th century (1800s) education for would-be elites consisted of Greek and Roman military histories omitting the weaknesses and costs, plus Biblical Jewish fanaticism and the Church's expensive preacher propagandists. |

Revealing list of titles by Chapman Cohen, all undated, none with comment on the contents. A title Materialism probably looked at 'dialectical materialism', a prop for Jewish historiography, navigating uneasily between the Jewish view of Christianity (Jews invented it, but a lot of benefit went to churchmen) and the Jewish view of Jews (Jews invented themselves as G-d, and they're chosen). Socialism and the Churches probably refers to the USSR, which Jews habitually said was 'socialist'. Plenty of scope for evasion and annoyance against non-Jews. Spain and the Church must refer to the Spanish Civil War, omitting the Jewish invasion elements and omitting everything about Jews and Marranos in Spain. Theism or Atheism? The great alternative must be part of the insistence of a single God (i.e. the Jewish idea) as opposed to the obvious truth of atheism—or the acceptance of any number of non-existent constructions. Determinism or Free-Will must take into account the supposed Calvinist elect, the idea that people are permanently chosen. Blasphemy. A plea for religious equality must be aimed to allow Jews to insult Christianity, while not troubling with the response that Christians should be allowed to insult Jews. Foundations of Religion is Cohen's lecture at Manchester College, Oxford—a northern England college, becoming the 39th college only in 1996. It's small and post-graduate, probably like the 'Oxford Union', a place for Jews to infiltrate maybe doing advanced Frankfurt-school style PPE stuff; it's now Harris Manchester College. Cohen has a title on slavery—no prizes for expecting Jews and slave-trading to be unmentioned. Revealing list of titles by Chapman Cohen, all undated, none with comment on the contents. A title Materialism probably looked at 'dialectical materialism', a prop for Jewish historiography, navigating uneasily between the Jewish view of Christianity (Jews invented it, but a lot of benefit went to churchmen) and the Jewish view of Jews (Jews invented themselves as G-d, and they're chosen). Socialism and the Churches probably refers to the USSR, which Jews habitually said was 'socialist'. Plenty of scope for evasion and annoyance against non-Jews. Spain and the Church must refer to the Spanish Civil War, omitting the Jewish invasion elements and omitting everything about Jews and Marranos in Spain. Theism or Atheism? The great alternative must be part of the insistence of a single God (i.e. the Jewish idea) as opposed to the obvious truth of atheism—or the acceptance of any number of non-existent constructions. Determinism or Free-Will must take into account the supposed Calvinist elect, the idea that people are permanently chosen. Blasphemy. A plea for religious equality must be aimed to allow Jews to insult Christianity, while not troubling with the response that Christians should be allowed to insult Jews. Foundations of Religion is Cohen's lecture at Manchester College, Oxford—a northern England college, becoming the 39th college only in 1996. It's small and post-graduate, probably like the 'Oxford Union', a place for Jews to infiltrate maybe doing advanced Frankfurt-school style PPE stuff; it's now Harris Manchester College. Cohen has a title on slavery—no prizes for expecting Jews and slave-trading to be unmentioned.

But note what's omitted—Cohen avoided many tricky topics: the United States Civil War, India and the East India Co, China and Opium, the 'Great War', suffragists and suffragettes, Lenin and Stalin, Hitler and Germany! |

Chapman Cohen's 50-page introduction to this 1937 edition of The Age of Reason proved astonishingly helpful to me—and I'd expect to any reader who understands something of Jewish lies and psychology. He makes it completely clear whose side he says he's on—(direct quotations in small text here)—the 'French Revolution'. ['most significant event in modern times - the French revolution of 1789 .. the first decisive break from the old order, a small minority with all the power and privileges, on the other hand the vast mass of the people possessing - nothing. The crown, the nobility - and the Church, which owned nearly a third of the land of France. Enlightened men and women hailed the revolution as offering a charter of human freedom...]

In true Jewish style, he hates Christianity. Or at least that's his pose, since Christianity is an offshoot of Judaism. It's his pose when he wants it to be: 'an attack on the Christian fortress'.

And in true Jewish style, like South Place in London, Cohen likes what he calls Freethinkers, a codeword for critics of Christianity who fail to criticise Jews. Scientists and Philosophers like Deism. Christians are good and sustained haters ... killing a man by ignoring his work and Christianity is a hotch-potch of primitive superstitions and savage customs

Inherited religious bigotry is illustrated by Cohen, not with Jewish ideas, but with the description by Theodore Roosevelt of Paine as filthy little Atheist. No, says Cohen, Paine was a theist. Believing in the Jewish one and only God. ..great principle of divine morality, justice, and mercy.. Yes, of course, Cohen...

Cohen disliked the Bible (but says nothing about the Talmud). ...dead ideas such as literal inspiration of the Bible And indeed the King James Bible (of 1611) must have left a feeling of disgust and ridicule; and this may have been part of the long-term policy of Jewish leaders. By 1794, The Age of Reason probably was intended to be sweepingly successful. I suspect the extreme dogmatic silliness in the USA came as a surprise.

Paine's work incomparable. ... careless of his rights as a author .. not a professional writer ... men and women went to prison for selling it... still a best-seller is worryingly unlikely; if Paine was extremely poor, how could he fund hundreds of thousands of booklets? Were there really hundreds of people willing to be jailed?—all looks like what Miles Mathis calls a 'project'.

My best guess after a close reading of Cohen is that the Burke vs Paine arguments were controlled opposition, Burke getting his secret pension in exchange for his stodgy defence of establishments and his opposition to the "rebels", advising Marie Antoinette to appeal to foreign armies. Cohen says thousands of English people know of Burke's Reflections on the French Revolution only because Paine wrote The Rights of Man in reply.

Here's an example of Paine in full flow, very keen on government:– Just a sample of his style:– ‘There never did, there never will, and there never can exist a Parliament, or any description of men, or any generation of men, in any country, possessed of the right or the power of binding and controlling posterity to 'the end of time', or to commanding forever how the world shall be governed, or who shall govern it; and therefore all such clauses, acts or declarations by which the makers of them attempt to do what they have neither the right nor the power to do, nor the power to execute, are in themselves null and void.’

Paine was Induced by Franklin to go to America... offered charge of The Pennsylvania Magazine .. joined armed men wrote the first number of The Crisis [on the summer soldier and sunshine patriot]

Paine went back to Europe in 1787. He was supposed to have been a great inventor, but since the iron bridge in Ironbridge was built by 1779, this looks another fake. Possibly an attempt to buy patents.

Were 'Freethinkers' just more crypto-Jews?

Some names quoted are Leslie Stephen, J M Robertson, W E H Lecky, J R Green, and Moncure Conway. Conway has a high position in the rather out-of-the-way world of crypto-Jewish apologetics. I was struck by his omission of Walter Scott's views on Jews and the French Revolution, and by the losses and destruction of evidence relating to Paine. I have to say Conway seems a type of crypto-Jew. I'll stop here (life is short!) in the hope that the 'founding fathers' and Constitution of the United States will be demystified. Preferably not in the remote future!

For reference, I've downloaded from archive.org two pdf books by Moncure Conway (1832-1907). 'Moncure' seems not to be a religious title, but a family name). I'm afraid my patience was not up to the task of finding uniform editions.

Biography of Thomas Paine vol. 1 by Moncure Conway (1908. 7 MB, pdf format). Many of Paine's papers were destroyed; Conway received little help with his books and could not be expected to investigate the French Revolution in detail.

Biography of Thomas Paine vol. 2 by Moncure Conway (1898. 18 MB, pdf format).

Paine's work were printed in numerous formats, some of which perhaps were proof-read by Paine. The best old edition is by Moncure Conway, but is in 4 volumes (1894-1896). So here is

Complete works of Thomas Paine (54 MB, pdf format).

The Fate of Thomas Paine by Bertrand Russell (1934)

Thomas Paine, though prominent in two revolutions and almost hanged for attempting to raise a third, is grown, in our day, somewhat dim. To our great grandfathers, he seemed a kind of earthly Satan, a subversive infidel rebellious alike against his God and his King. He incurred the bitter hostility of three men not generally united: Pitt, Robespierre, and Washington. Of these, the first two sought his death, while the third carefully abstained from measures designed to save his life. Pitt and Washington hated him because he was a democrat; Robespierre, because he opposed the execution of the King and the Reign of Terror. It was his fate to be always honored by opposition and hated by governments: Washington, while he was still fighting the English, spoke of Paine in terms of highest praise; the French nation heaped honors upon him until the Jacobins rose to power; even in England, the most prominent Whig statesmen befriended him and employed him in drawing up manifestoes. He had faults, like other men; but it was for his virtues that he was hated and successfully calumniated.Paine's importance in history consists in the fact that he made the preaching of democracy democratic. There were, in the eighteenth century, democrats among French and English aristocrats, among Philosophes and nonconformist ministers. But all of them presented their political speculations in a form designed to appeal only to the educated. Paine, while his doctrine contained nothing novel, was an innovator in the manner of his writing, which was simple, direct, unlearned, and such as every intelligent workingman could appreciate. This made him dangerous; and when he added religious unorthodoxy to his other crimes, the defenders of privilege seized the opportunity to load him with obloquy.

The first thirty-six years of his life gave no evidence of the talents which appeared in his later activities. He was born at Thetford in 1739, of poor Quaker parents, and was educated at the local grammar school up to the age of thirteen, when he became a stay-maker. A. quiet life, however, was not his taste, and at the age of seventeen he tried to enlist on a privateer called The Terrible, whose captain's name was Death. His parents fetched him back and so probably saved his life, as 175 out of the crew of 200 were shortly afterward killed in action. A little later, however, on the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, he succeeded in sailing on another privateer, but nothing is known of his brief adventures at sea. In 1758, he was employed as a staymaker in London, and in the following year he married, but his wife died after a few months. In 1763 he became an exciseman, but was dismissed two years later for professing to have made inspections while he was in fact studying at home. In great poverty, he became a schoolmaster at ten shillings a week and tried to take Anglican orders. From such desperate expedients he was saved by being reinstated as an exciseman at Lewes, where he married a Quakeress from whom, for reasons unknown, he formally separated in 1774. In this year he again lost his employment, apparently because he organized a petition of the excisemen for higher pay. By selling all that he had, he was just able to pay his debts and leave some provision for his wife, but he himself was again reduced to destitution. In London, where he was trying to present the excisemen's petition to Parliament, he made the acquaintance of Benjamin Franklin, who thought well of him. The result was that in October 1774 he sailed for America, armed with a letter of recommendation from Franklin describing him as an "ingenious, worthy young man." As soon as he arrived in Philadelphia, he began to show skill as a writer and almost immediately became editor of a journal. His first publication, in March 1775, was a forcible article against slavery and the slave trade, to which, whatever some of his American friends might say, he remained always an uncompromising enemy. It seems to have been largely owing to his influence that Jefferson inserted in the draft of the Declaration of Independence the passage on this subject which was afterward cut out. In 1775, slavery still existed in Pennsylvania; it was abolished in that state by an Act of 1780, of which, it was generally believed, Paine wrote the preamble. Paine was one of the first, if not the very first, to advocate complete freedom for the United States. In October 1775, when even those who subsequently signed the Declaration of Independence were still hoping for some accommodation with the British Government, he wrote:

"I hesitate not for a moment to believe that the Almighty will finally separate America from Britain. Call it Independency or what you will, if it is the cause of God and humanity it will go on. And when the Almighty shall have blest us, and made us a people dependent only upon him, then may our first gratitude be shown by an act of continental legislation, which shall put a stop to the importation of Negroes for sale, soften the hard fate of those already here, and in time procure their freedom."

It was for the sake of freedom freedom from monarchy, aristocracy, slavery, and every species of tyranny that Paine took up the cause of America.

During the most difficult years of the War of Independence he spent his days campaigning and his evenings composing rousing manifestoes published under the signature "Common Sense." These had enormous success and helped materially in winning the war. After the British had burned the towns of Falmouth in Maine and Norfolk in Virginia, Washington wrote to a friend (January 37, 1776): "A few more of such flaming arguments as were exhibited at Falmouth and Norfolk, added to the sound doctrine and unanswerable reasoning contained in the pamphlet Common Sense, will not leave numbers at a loss to decide upon the propriety of separation." The work was topical and has now only a historical interest, but there are phrases in it that are still telling. After pointing out that the quarrel is not only with the King, but also with Parliament, he says: "There is no body of men more jealous of their privileges than the Commons: because they sell them." At that date it was impossible to deny the justice of this taunt.

There is vigorous argument in favor of a Republic, and triumphant refutation of the theory that monarchy prevents civil war. "Monarchy and succession," he says, after his summary of English history, "have laid ... the world in blood and ashes. 'Tis a form of government which the word of God bears testimony against, and blood will attend it." In December at a moment when the fortunes of war were adverse, Paine published a pamphlet called The Crisis, beginning: "These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman."

This essay was read to the troops, and Washington expressed to Paine a "living sense of the importance of your works." No other writer was so widely read in America, and he could have made large sums by his pen, but he always refused to accept any money at all for what he wrote. At the end of the War of Independence, he was universally respected in the United States but still poor; however, one state legislature voted him a sum of money and another gave him an estate, so that he had every prospect of comfort for the rest of his life. He might have been expected to settle down into the respectability characteristic of revolutionaries who have succeeded. He turned his attention from politics to engineering and demonstrated the, possibility of iron bridges with longer spans than had previously been thought feasible. Iron bridges led him to England, where he was received in a friendly manner by Burke, the Duke of Portland, and other Whig notables. He had a large model of his iron bridge set up at Paddington; he was praised by eminent engineers and seemed likely to spend his remaining years as an inventor.

However, France as well as England was interested in iron bridges. In 1788 he paid a visit to Paris to discuss them with Lafayette and to submit his plans to the Academic des Sciences, which, after due delay, reported favorably. When the Bastille fell, Lafayette decided to present the key of the prison to Washington and entrusted to Paine the task of conveying it across the Atlantic. Paine, however, was kept in Europe by the affairs of his bridge. He wrote a long letter to Washington informing him that he would find someone to take his place in transporting "this early trophy of the spoils of despotism, and the first ripe fruits of American principles transplanted into Europe." He goes on to say that "I have not the least doubt of the final and compleat success of the French Revolution," and that "I have manufactured a bridge (a single arch) of one hundred and ten feet span, and five feet high from the cord of the arch."

For a time, the bridge and the Revolution remained thus evenly balanced in his interests, but gradually the Revolution conquered. In the hope of rousing a responsive movement in England, he wrote his The Rights of Man on which his fame as a democrat chiefly rests.

This work, which was considered madly subversive during the anti-Jacobin reaction, will astonish a modern reader by its mildness and common sense. It is primarily an answer to Burke and deals at considerable length with contemporary events in France. The first part was published in 1791, the second in February 1792; there was, therefore, as yet no need to apologize for the Revolution. There is very little declamation about Natural Rights, but a great deal of sound sense about the British Government. Burke had contended that the Revolution of 1688 bound the British for ever to submit to the sovereigns appointed by the Act of Settlement. Paine contends that it is impossible to bind posterity, and that constitutions must be capable of revision from time to time.

Governments, he says, "may all be comprehended under three heads. First, superstition. Secondly, power. Thirdly, the common interest of society and the common rights of man. The first was a government of priestcraft, the second of conquerors, the third of reason." The two former amalgamated: "the key of St. Peter and the key of the Treasury became quartered on one another, and the wondering, cheated multitude worshippd the invention." Such general observations, however, are rare. The bulk of the work consists, first, of French history from 1789 to the end of 1791 and, secondly, of a comparison of the British Constitution with that decreed in France in 1791, of course to the advantage of the latter. It must be remembered that in 1791 France was still a monarchy. Paine was a republican and did not conceal the fact, but did not much emphasize it in The Rights of Man.

Paine's appeal, except in a few short passages, was to common sense. He argued against Pitt's finance, as Cobbett did later, on grounds which ought to have appealed to any Chancellor of the Exchequer; he described the combination of a small sinking fund with vast borrowings as setting a man with a wooden leg to catch a hare—the longer they run, the farther apart they are. He speaks of the "Potter's field of paper money"—a phrase quite in Cobbett's style. It was, in fact, his writings on finance that turned Cobbett's former enmity into admiration. His objection to the hereditary principle, which horrified Burke and Pitt, is now common ground among all politicians, including even Mussolini and Hitler. Nor is his style in any way outrageous: it is clear, vigorous, and downright, but not nearly as abusive as that of his opponents.

Nevertheless, Pitt decided to inaugurate his reign of terror by prosecuting Paine and suppressing The Rights of Man. According to his niece, Lady Hester Stanhope, he "used to say that Tom Paine was quite in the right, but then, he would add, what am I to do? As things are, if I were to encourage Tom Paine's opinions we should have a bloody revolution." Paine replied to the prosecution by defiance and inflammatory speeches. But the September massacres were occurring, and the English Tories were reacting by increased fierceness. The poet Blake—who had more worldly wisdom than Paine—persuaded him that if he stayed in England he would be hanged. He fled to France, missing the officers who had come to arrest him by a few hours in London and by twenty minutes in Dover, where he was allowed by the authorities to pass because he happened to have with him a recent friendly letter from Washington.

Although England and France were not yet at war, Dover and Calais belonged to different worlds. Paine, who had been elected an honorary French citizen, had been returned to the Convention by three different constituencies, of which Calais, which now welcomed him, was one. "As the packet sails in, a salute is fired from the battery; cheers sound along the shore. As the representative for Calais steps on French soil soldiers make his avenue, the officers embrace him, the national cockade is presented"—and so on through the usual French series of beautiful ladies, mayors, etc.

Arrived in Paris, he behaved with more public spirit than prudence. He hoped—in spite of the massacres—for an orderly and moderate revolution such as he had helped to make in America. He made friends with the Girondins, refused to think ill of Lafayette (now in disgrace), and continued, as an American, to express gratitude to Louis XVI for his share in liberating the United States. By opposing the King's execution down to the last moment, be incurred the hostility of the Jacobins. He was first expelled from the Convention and then imprisoned as a foreigner; he remained in prison throughout Robespierre's period of power and for some months longer. The responsibility rested only partly with the French; the American Minister, Gouverneur Morris, was equally to blame. He was a Federalist and sided with England against France; he had, moreover, an ancient personal grudge against Paine for exposing a friend's corrupt deal during the War of Independence. He took the line that Paine was not an American and that he could therefore do nothing for him. Washington, who was secretly negotiating Jay's treaty with England, was not sorry to have Paine in a situation in which he could not enlighten the French Government as to reactionary opinion in America. Paine escaped the guillotine by accident but nearly died of illness. At last Morris was replaced by Monroe (of the "Doctrine"), who immediately procured his release, took him into his own house, and restored him to health by eighteen months' care and kindness.

Paine did not know how great a part Morris had played in his misfortunes, but he never forgave Washington, after whose death, hearing that a statue was to be made of the great man, he addressed the following lines to the sculptor:

Take from the mine the coldest, hardest stone, It needs no fashion: it is Washington. But if you chisel, let the stroke be rude, And on his heart engrave—Ingratitude.

This remained unpublished, but a long, bitter letter to Washington was published in 1796, ending:

And as to you, Sir, treacherous in private friendship (for so you have been to me, and that in the day of danger) and a hypocrite in public life, the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an impostor; whether you have abandoned good principles, or whether you ever had any.

To those who know only the statuesque Washington of the legend, these may seem wild words. But 1796 was the year of the first contest for the Presidency, between Jefferson and Adams, in which Washington's whole weight was thrown into support of the latter, in spite of his belief in monarchy and aristocracy; moreover, Washington was taking sides with England against France and doing all in his power to prevent the spread of those republican and democratic principles to which he owed his own elevation. These public grounds, combined with a very grave personal grievance, show that Paine's words were not without justification.

It might have been more difficult for Washington to leave Paine languishing in prison if that rash man had not spent his last days of liberty in giving literary expression to the theological opinions which he and Jefferson shared with Washington and Adams, who, however, were careful to avoid all public avowals of unorthodoxy. Foreseeing his imprisonment, Paine set to work to write The Age of Reason, of which he finished Part 1 six hours before his arrest. This book shocked his contemporaries, even many of those who agreed with his politics. Nowadays, apart from a few passages in bad taste, there is very little that most clergymen would disagree with. In the first chapter he says:

"I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe in the equality of man, and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow creatures happy."

These were not empty words. From the moment of his first participation in public affairs—his protest against slavery in 1775—down to the day of his death, he was consistently opposed to every form of cruelty, whether practiced by his own party or by his opponents. The Government of England at that time was a ruthless oligarchy, using Parliament as a means of lowering the standard of life in the poorest classes; Paine advocated political reform as the only cure for this abomination and had to fly for his life. In France, for opposing unnecessary bloodshed, he was thrown into prison and narrowly escaped death. In America, for opposing slavery and upholding the principles of the Declaration of Independence, he was abandoned by the Government at the moment when he most needed its support. If, as he maintained and as many now believe, true religion consists in "doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow creatures happy," there was not one among his opponents who had as good a claim to be considered a religious man.

The greater part of The Age of Reason consists of criticism of the Old Testament from a moral point of view. Very few nowadays would regard the massacres of men, women, and children recorded in the Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua as models of righteousness, but in Paine's day it was considered impious to criticize the Israelites when the Old Testament approved of them. Many pious divines wrote answers to him. The most liberal of those was the Bishop of Llandaff, who went so far as to admit that parts of the Pentateuch were not written by Moses, and some of the Psalms were not composed by David. For such concessions he incurred the hostility of George III and lost all chance of translation to a richer see. Some of the Bishop's replies to Paine are curious.. For example, The Age of Reason ventured to doubt whether God really commanded that all males and married women among the Midianites should be slaughtered, while the maidens should be preserved. The Bishop indignantly retorted that the maidens were not preserved for immoral purposes, as Paine had wickedly suggested, but as slaves, to which there could be no ethical objection. The orthodox of our day have forgotten what orthodoxy was like a hundred and forty years ago. They have forgotten still more completely that it was men like Paine who, in face of persecution, caused the softening of dogma by which our age profits. Even the Quakers refused Paine's request for burial in their cemetery, although a Quaker farmer was one of the very few who followed his body to the grave.

After The Age of Reason Paine's work ceased to be important. For a long time he was very ill; when he recovered, he found no scope in the France of the Directoire and the First Consul. Napoleon did not ill-treat him, but naturally had no use for him, except as a possible agent of democratic rebellion in England. He became homesick for America, remembering his former success and popularity in that country and wishing to help the Jeffersonians against the Federalists. But the fear of capture by the English, who would certainly have hanged him, kept him in France until the Treaty of Amiens. At length, in October 1802, he landed at Baltimore and at once wrote to Jefferson (now President):

"I arrived here on Saturday from Havre, after a passage of sixty days. I have several cases of models, wheels, etc., and as soon as I can get them from the vessel and put them on board the packet for Georgetown I shall set off to pay my respects to you. Your much obliged fellow citizen,

THOMAS PAINE"

He had no doubt that all his old friends, except such as were Federalists, would welcome him. But there was a difficulty: Jefferson had a hard fight for the Presidency, and in the campaign the most effective weapon against him unscrupulously used by ministers of all denominations had been the accusation of infidelity. His opponents magnified his intimacy with Paine and spoke of the pair as "the two Toms." Twenty years later, Jefferson was still so much impressed by the bigotry of his compatriots that he replied to a Unitarian minister who wished to publish a letter of his: "No, my dear Sir, not for the world! ... I should as soon undertake to bring the crazy skulls of Bedlam to sound understanding as to inculcate reason into that of an Athanasian ... keep me therefore from the fire and faggot of Calvin and his victim. Servetus." It was not surprising that, when the fate of Servetus threatened them, Jefferson and his political followers should have fought shy of too close an association with Paine. He was treated politely and had no cause to complain, but the old easy friendships were dead.

In other circles he fared worse. Dr. Rush of Philadelphia, one of his first American friends, would have nothing to do with him: "... his principles" he wrote, "avowed in his Age of Reason, were so offensive to me that I did not wish to renew my intercourse with him." In his own neighborhood, he was mobbed and refused a seat in the stagecoach; three years before his death he was not allowed to vote, on the alleged ground of his being a foreigner. He was falsely accused of immorality and intemperance, and his last years were spent in solitude and poverty. He died in 1809. As he was dying, two clergymen invaded his room and tried to convert him, but he merely said, "Let me alone; good morning!" Nevertheless, the orthodox invented a myth of deathbed recantation which was widely believed.

His posthumous fame was greater in England than in America. To publish his works was, of course, illegal, but it was done repeatedly, although many men went to prison for this offense. The last prosecution on this charge was that of Richard Carlile and his wife. In 1819 he was sentenced to prison for three years and a fine of fifteen hundred pounds, she to one year and five hundred pounds. It was in this year that Cobbett brought Paine's bones to England and established his fame as one of the heroes in the fight for democracy in England. Cobbett did not, however, give his bones a permanent resting place. "The monument contemplated by Cobbett," says Moncure Conway, "was never raised." There was much parliamentary and municipal excitement. A Bolton town crier was imprisoned nine weeks for proclaiming the arrival. In 1836 the bones passed with Cobbett's effects into the hands of a receiver (West). The Lord Chancellor refusing to regard them as an asset, they were kept by an old day laborer until 1844, when they passed to B. Tilley, 13 Bedford Square, London, a furniture dealer. In 1854, Rev. R. Ainslie (Unitarian) told E. Truelove that he owned "the skull and the right hand of Thomas Paine," but evaded subsequent inquiries. No trace now remains, even of the skull and right hand.

Paine's influence in the world was twofold. During the American Revolution he inspired enthusiasm and confidence, and thereby did much to facilitate victory. In France his popularity was transient and superficial, but in England he inaugurated the stubborn resistance of plebeian Radicals to the long tyranny of Pitt and Liverpool. His opinions on the Bible, though they shocked his contemporaries more than his Unitarianism, were such as might now be held by an archbishop, but his true followers were the men who worked in the movements that sprang from him those whom Pitt imprisoned, those who suffered under the Six Acts, the Owenites, Chartists, Trade-Unionists, and Socialists. To all these champions of the oppressed he set an example of courage, humanity, and single-mindedness. When public issues were involved, he forgot personal prudence. The world decided, as it usually does in such cases, to punish him for his lack of self-seeking; to this day his fame is less than it would have been if his character had been less generous. Some worldly wisdom is required even to secure praise for the lack of it.

© Raeto West 5-10 March 2024