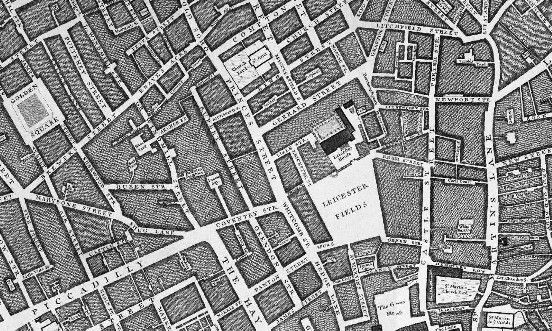

1746 London. 'Leicester Fields' came to be named 'Leicester Square'. Note Castle Street to its east. Golden Square was one of John Hunter's residences; the other was in Earl's Court (off the map, to the west). A few churchyards are included in the map.

1714 - Fahrenheit's mercury thermometer invented

1728 - John Hunter born 13/14 February at Long Calderwood, East Kilbride

1748 - Joins his brother William at his anatomy school in London

1754 - Becomes a pupil at St George's Hospital; discovers placental circulation

1756 - Spends five months as a house surgeon at St George's

1759 - British Museum opened

1760 - Enlists as a surgeon in the army

1762 - Hunter's first research paper, on the descent of the testes and congenital hernias, published in William's Medical Commentaries

1763 - Leaves army and sets up practice in London

1764 - Becomes engaged to Anne Home

1766 - First paper, on the Siren Lacertina, an 'eel-like amphibian', published by Royal Society

1767 - Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). Begins experiment on venereal diseases, perhaps on himself

1768 - Appointed surgeon at St George's. (Unpaid - p 307)

1770 - Edward Jenner, a 'kindred spirit', becomes Hunter's house pupil

1771 - Publishes first major work, The Natural History of the Human Teeth; marries Anne Home

1775 - Offers private lectures on surgery

1776 - Appointed Surgeon Extraordinary to George III; treats David Hume

1777 - Attempts to revive Revd William Dodd after hanging

1778 - Publishes A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth

1779 - Publishes 'An account of the free-martin' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

1780 - Accuses brother of stealing his discovery of placental circulation

1783 - Moves to Leicester Square; steals body of Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant

1785 - Consulted by Benjamin Franklin; performs popliteal aneurysm operation

1786 - Treats William Pitt; awarded Copley Medal by RS; publishes A Treatise on the Venereal Disease

1787 - Treats Adam Smith

1788 - 28 Leicester Square Museum opens twice a year; treats Thomas Gainsborough and young Byron

1790 - Appointed surgeon-general of the army

1792 - Begins writing Observations and Reflections on Geology

1793 - John Hunter died 16 October at St George's

1809 - Birth of Darwin

1823 - Birth of Alfred Russel Wallace

1850 - Gray's Anatomy 1st edition

1728 - John Hunter born 13/14 February at Long Calderwood, East Kilbride

1748 - Joins his brother William at his anatomy school in London

1754 - Becomes a pupil at St George's Hospital; discovers placental circulation

1756 - Spends five months as a house surgeon at St George's

1759 - British Museum opened

1760 - Enlists as a surgeon in the army

1762 - Hunter's first research paper, on the descent of the testes and congenital hernias, published in William's Medical Commentaries

1763 - Leaves army and sets up practice in London

1764 - Becomes engaged to Anne Home

1766 - First paper, on the Siren Lacertina, an 'eel-like amphibian', published by Royal Society

1767 - Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). Begins experiment on venereal diseases, perhaps on himself

1768 - Appointed surgeon at St George's. (Unpaid - p 307)

1770 - Edward Jenner, a 'kindred spirit', becomes Hunter's house pupil

1771 - Publishes first major work, The Natural History of the Human Teeth; marries Anne Home

1775 - Offers private lectures on surgery

1776 - Appointed Surgeon Extraordinary to George III; treats David Hume

1777 - Attempts to revive Revd William Dodd after hanging

1778 - Publishes A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth

1779 - Publishes 'An account of the free-martin' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

1780 - Accuses brother of stealing his discovery of placental circulation

1783 - Moves to Leicester Square; steals body of Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant

1785 - Consulted by Benjamin Franklin; performs popliteal aneurysm operation

1786 - Treats William Pitt; awarded Copley Medal by RS; publishes A Treatise on the Venereal Disease

1787 - Treats Adam Smith

1788 - 28 Leicester Square Museum opens twice a year; treats Thomas Gainsborough and young Byron

1790 - Appointed surgeon-general of the army

1792 - Begins writing Observations and Reflections on Geology

1793 - John Hunter died 16 October at St George's

1809 - Birth of Darwin

1823 - Birth of Alfred Russel Wallace

1850 - Gray's Anatomy 1st edition

Hunter amassed a vast collection of specimens and 'preparations', which in effect seem to have been of three types:

- Spectacular objects—for example a stuffed giraffe, the first ever seen in Britain;

- Ordered and sorted specimens, showing similar structures in different species (e.g. skeletal structures, tendrils...), or similar processes in different species (circulation, digestion, breathing...), or developments in the same species (e.g. eggs developing up to the point of hatching). And

- Unusual or pathological specimens. He wasn't the same type as typical Victorian collectors, with birds' eggs in mahogany cases.

There's a handy chronology by 'big Al' on Moore's website, which I hope they won't mind me repeating here (with a few changes).

John Hunter did not have a conventional career. He came to London, following his brother, with a background in investigating the life all around him in Scotland. He may have been 'dyslexic'; he was reluctant to use neologisms, though he needed them—'embryology' would have been useful—perhaps he felt the lack of Greek and Latin; he disliked medical books, which of course were based on traditional errors; he disliked lecturing, perhaps conscious of a heavy accent; he was amiable though laconic—the testimonies are somewhat varied and inconsistent. But they all insist he worked, possibly to the limits of human ability, and largely on dissections and examinations of all the life forms then known. He was unequalled in this.

His income came from private practice and students' fees [p. 409] but he spent heavily. His museum was opened in 1788, in (I think) his Leicester Square house. The map section (right) shows Leicester Fields, a name that seems to have been interchangeable with Leicester Square, judging by 18th century maps. Note Castle Street to its east: the back of the Leicester Square house had less elegant housing to its rear, where deliveries could be made by 'resurrection men' and other more respectable types. His death was only about five years later; he bequeathed debts. And the Leicester Square house had only a short remaining lease. Anne, his wife, 'Leaving her elegant home and servants and abandoning her circle of literary and musical friends ... was forced at fifty-one to take a job as a ladies' chaperone...' Perhaps Everard Home considered himself justified in collecting honours and money; perhaps he helped his sister, though one suspects not.

The Hunterian Museum now, at the Royal College of Surgeons, is illustrated by a reproduction of an 1840 watercolour in Moore's book. It shows what looks like a caissoned ceiling, with curved side windows and upper and lower book- or specimen-lined galleries, with colonnades of pillars and huge display cases at floor level.

Hunter dissected a few thousand human corpses. And made 'preparations'—for example of the unfortunate Irish giant, Charles Byrne, victim of a pituitary tumour, though nobody knew that at the time. After death, the body, in a lead coffin to be buried at sea, was intercepted, removed, and taken back to Hunter, who cut off the flesh and boiled the body, then assembled the bones with, presumably, thread or wire. Total cost believed to be £500. Moore discusses 'resurrection men' in some detail. The procedure was something like the Thuggees in reverse, digging at the head end of a fresh grave, smashing the coffin, tugging up the corpse. They seem to have avoided murder, perhaps on legal advice, or because of the fear of the Tyburn tree. The trade seems to have received its death knell (so to speak) when murders became noticed. Wendy Moore has not looked in detail into the legal system of the time; how did they get away with stealing bodies? How did anatomists get away with frequent human dissections? There are modern equivalents, of course, to legal blind eye turning.

Hunter regarded human beings as 'the most perfect animal' [p 498] but classified monkeys and inferior races (I'm not sure if that's his expression) on a continuum. He came within a whisker of inventing evolutionary theory, and indeed it's an astonishing fact that Wallace was so late relatively: surely Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, or British seamen might have constructed such a theory? All that's needed is a feeling for long stretches of time and space, feeling for inheritance, and some conception of needs of food and shelter and reproduction. And some freedom of thought and action.

But human specimens were a tiny proportion of his collection: '.. eventually it would encompass more than 1,400 animal and human parts preserved in spirits [i.e. alcohol]; over 1,200 dried bones, skulls, and skeletons; more than 6,000 pathological specimens ...; and more than 800 dried plants and invertebrates, as well as ... stuffed animals, corals, minerals and shells. ... more than 500 different species ... nearly 3,000 fossils ..' [p 468].

Hunter taught surgeons-to-be; a total of about 1,000. Some went to the USA, others to hospitals in Britain. Despite his supposed dislike of lecturing, he was popular, far more than rivals, if others can be even considered rivals. Three names—Caesar Hawkins, William Bromfield, and John Gunning [p 305], (and later Thomas Keate, and William Walker)—represented the old guard, bloodletting, cupping, and killing. [p 55 has incredulous accounts of traditional techniques]. Or, more precisely, instructing others to do the dirty work.

The medical 'professoriat' disliked Hunter. They seem to have commissioned a hostile book by Jessé Foot for £400 after Hunter's death. [p 527] The grounds seem to have been that he was an unqualified showman and mountebank. It's interesting to contemplate how single-minded Hunter had to be. If he'd never lived, perhaps phlebotomy and anal bellows would be current practices. There are many analogies at the present day: just two of them are fluoride, a poison put into otherwise clean water; and 'AIDS', so far a thirty-year fraud. Psychology is at present at something like the level of surgery in the 18th century; empiricism seems unavoidable. Maybe in future years there will be exhibits of the brains and biochemical systems of Henry Kissinger and George Soros in some museum of monstrosities.

The process of 'professionalisation' had barely started: the Royal Society (c 1660), and for example the British Museum (c 1753) and Royal Academy (c 1768) had been founded in Hunter's time, and the Royal Institution (c 1799) after Hunter's death, but specialised learned societies with acceptable qualifications were in the future. The everyday system then was more like apprenticeship, not surprising where there was little general education.

Empirically, though, Hunter's grasp of anatomy made him indispensable. Moore gives an account of a caesarian section, at that time a rarity. In principle, it looks fairly simple: a bulging abdomen, and some sort of knife. But of course the ethical surgeon would not wish to cut off or damage bits. P 309 gives an account—the operation, as the old joke goes, was successful, but both patients, mother and child, died fairly soon. But it was obvious Hunter was competent. This sort of thing produced a change in the social atmosphere: after a few decades, post mortems became accepted, we're told.

The sciences generally were making progress: a good example is Scheele, (1742-1786) who was said to have discovered more new chemical substances than anyone else. Priestley (1733-1804) is generally credited with discovering oxygen in 1774 (his birthplace was Birstall, scene of likely false flag killing of Jo Cox MP), though as far as I know Hunter did not incorporate oxygen in his biology. Lavoisier (1743-1794) invented, or perhaps just arranged, modern chemistry before Dalton (1766-1844).

In Hunter's world, hydrochloric acid was known, and had been for centuries, but of course its composition wasn't known, and the name was in the future. Oxygen, hydrogen, proteins and their properties were mostly in the future. Opium and alcohol were the only anaesthetics. The electric eel was not understood, since electricity itself was not understood. Microscopes had been publicised about a century before Hunter started his work in London [Robert Hooke's Micrographia was 1665] but microscopes have only two mentions in Moore's book. It seems fair to regard Hunter as mostly a naked eye worker, not unreasonably, since the fine detail must have been almost impossible to decode. To this day, microscopic structures cause problems, notably artefact of electron microscopy. Hunter did however make use of instrument makers, for example for specialised thermometers, I'd guess working in the Clerkenwell area.

Portrait of John Hunter hanging at the Royal Society. The artist, Robert Home, was his wife's brother, and brother of Everard Home. The dog may be Lion, his wolf-dog hybrid.

And Captain Cook's return to England in 1771 after a few years sailing the south Pacific in the Endeavour with Joseph Banks and others [p 284, departure from Plymouth; p 317, return to Deal, in Kent] 'brought back ... 1,400 new plant species, more than a thousand new species of animals ..., more than a hundred birds, over 240 fish, and ... molluscs, insects, and marine creatures'. These were (I think) all preserved in some way: they may have liked a live kangaroo, for example, but the tiny ship could not accommodate one.

An interesting aspect of John Hunter's life work was his experiments with what are now called genetics. He successfully tried artificial insemination of silkworm eggs [p 280] which Moore thinks was pioneering, though surely livestock breeders must have used such methods long before. Interbreeding between species, or claimed species, was important, to try to fix boundaries, if any, between species. Hunter tried interbreeding domestic dogs (themselves of course of many varieties), and jackals, wolves, and foxes. [Published in 1878 by the Royal Society: p 491]. Jenner wrote to Hunter: 'The little jackal-bitch you gave me is grown a fine handsome animal; but she certainly does not possess the understanding of common dogs. She is easily lost when I take her out, and is quite inattentive to a whistle.' Thus, part of the effect of increased transport around the world was the possibility of reuniting long-separated animal groups, which evolved separately for many generations. This presumably is relevant to human races, about which Hunter probably wrote, though, if so, Wendy Moore is a bit evasive.

Moore is good on the social side of 18th century London, and I'd guess she may have been trained in Eng lit. She talks of Dr Johnson and his biographer Boswell (Sam Johnson 1709-1784; James Boswell 1740-1795). And of Smollett and Laurence Sterne. And Byron (Hunter recommended treatment for his foot, which Byron appears to have been too impoverished to carry out at the time. William Blake lived within sight of Castle Street, and probably referred to Hunter as 'Jack Tearguts'. Robert Louis Stevenson's Jekyll and Hyde may have been suggested the contrast between by Hunter's opulent Leicester Square façade and the unattractive resurrection men back entrance.

David Hume (philosopher), Adam Smith (economist), Benjamin Franklin, George III, Prime Ministers, and other aristocrats and well-known persons flicker through Moore's book, usually when near death. She's also good on artists: with no photography, drawings were necessary. Joshua Reynolds painted a couple of portraits of Hunter, one, which his wife disliked, with a fuzzy beard. Joseph Wright of Derby painted scenes of experiments, though I'm not certain these bear the usual modern interpretation. But the most important artist for Hunter was Jan van Rymsdyk (1730-1790) who drew quickly and slickly; I presume his works were engraved for reproduction on paper; they seem free of the fuzziness of etchings. His drawing of a foetus is far more impressive than Leonardo da Vinci's sketch.

Moore is not good on the power politics of the time. It's clear enough now that, after about a century, the Jews in the Bank of England were extending tentacles everywhere, not unlike on of Hunter's expanding growths. Culloden in 1746 was a last gasp of non-Jewish monarchy. The newly United States of America had an issue with the East India Company in 1775. France in 1789 had an issue with Jewish anti-Catholic Church activity. The results of these and many other events were far-reaching. It's likely enough that George III was poisoned, a favourite activity of Jews. However, Hunter probably had no inkling of any of this, beyond perhaps wondering about rents and leases, lack of public money for science, and what things like 'the Spanish Succession' had implied. There was, at the time, little overt Jewish control over opinions, freedom of enquiry, and research, in dramatic contrast with the present day.