1960s thinkers. Revisionist view of British philosophers and historians, defeated by world Jewry.

Ved Mehta: Fly and the Fly-Bottle: Encounters with British Intellectuals

• Indian writer talks with, and quotes philosophers and historians in Oxford, Cambridge, London, and Utrecht in 1961-1962 16 January 2021

• Not so much history of ideas as history of funded wrong ideas.

• The 'New Yorker' employed Ved Mehta, b 1934, then aged about 26, and (presumably) funded him, to visit Britain and Holland, in 1961 and 1962.

I hesitate to call Mehta a 'New Yorker writer', since he was redespatched to the old world very soon after being taken on. He'd read history at Oxford, and I think because of that must have been sent to report events—disputes over A J P Taylor's Origins of the Second World War—in which I now think Taylor was assisting world Jewry to continue with their fake World War 2 narratives—and disputes over Ernest Gellner's 'Words and Things' in which Gellner was supported by Bertrand Russell against 'linguistic philosophers', mostly from 1950s Oxford. The philosophical aim remains obscure, but my best guess is that Jews wanted to cut off possible serious philosophy, leaving only unimportant matters. Of course they were successful; philosophy in Britain has remained insignificant.

While in Europe, Mehta called on Arnold J. Toynbee, who'd just finished his multi-volume Study of History, which had been started before WW2, presumably as a project for the 'Royal Institute of International Affairs' running up to WW2; at the time it caused a stir of sorts, but of course did nothing to explain world history, and soon enough died), and on E H Carr (who'd just written What is History? and was one-third through his history of Soviet Russia, proving that he didn't know), and Herbert Butterfield (a very ordinary Oxford man best known for pretending science depended on Christianity), and others.

The full line-up is: Gilbert Ryle, Ernest Gellner, Bertrand Russell, Richard Hare, A J Ayer, P F Strawson, Iris Murdoch, G J Warnock, Stuart Hampshire, Hugh Trevor-Roper [later Lord Dacre], A J P Taylor, Toynbee, Pieter Geyl, E H Carr, C V Wedgwood, Christopher Hill, R H Tawney, John Brooke, Herbert Butterfield. Some were dead by then, off-stage, such as Sir Lewis Namier, the allegedly brilliant Jewish historian who at the time was given something like the Einstein treatment.

Mehta gives attractive and lucid descriptions, including snippets on travel, living rooms, voices, menus, clothes and so on, as well as Mehta's more or less verbatim interviews, which seem all to have been taped, plus a few extracts from printed material. The intellectual material avoids any controversial matter, in the normal sense of this website.

Note that Mehta is described as having been blind since the age of four—which sounds incredible to me. This may mean 'not being able to read the top letter on the Snellen eye chart'.

Another collection of pieces by Mehta, published as 'The New Theologian', looked at British theologians of more or less the same period.

Mehta's brief pen-portraits are attractive and skilful, and may well leave you wanting more. My view now (years later) is that the New Yorker was a Jewish propaganda outlet, and that the whole Mehta project was to push Jewish ideas.

Rae West - Mostly October 2010

In comments on Mehta's books, Wittgenstein is listed, though he died in 1951. J L Austin ('linguistic philosopher') died in Feb 1960; he generally had a poor press; he was a precisian English linguist rather than a philosopher. Lewis Namier died in Aug 1960. R H Tawney (Religion and the Rise of Capitalism) died in 1962. It's a pity C P Snow and F R Leavis weren't included as their 'Two Cultures' row was contemporary; Isaiah Berlin and Karl Popper would have been worthwhile subjects, but for reasons not given were not included, despite their obvious fittingness. Other subjects might have been Winston Churchill (Part I of The Second World War was published in 1948; nobody mentioned it—though it emerged later that other 'historians' submitted first drafts, to which Churchill added his embellishments), G M Trevelyan who died in 1962 (author of English Social History, no doubt another project), and Cambridge University's Joseph Needham of Science and Civilisation in China (Vol 1, 1954). Bullock's Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (published first in 1952) sold in large numbers despite its flaws (as David Irving said), its Penguin paperback nature signalling warnings. Here's a Alan Bullock recording of Bullock on Hitler and Stalin. Mehta doesn't mention him. It's unlikely Sir Oswald Mosley would have been selected).

• Ten Years Later. Much more on Ved Prakash Mehta's book...

I found his writing appealing, and decided to burrow more into his early 1960s accounts of Oxford. At the time of this writing, Ved Mehta is still alive, and I wondered if the USA at that time—represented by Jews—was exploring expansion into India, in the way it was invading China with its 'revolution'. By pure chance, I found a reference to the Marwani, described as India's moneylending caste and near-monopolist of Indian newspapers. How true this is, I don't know: I could find nothing in my 1910-1911 Britannica. I hope Mehta might add to revisionist views on the British and Moslems in India.

The New Yorker is just another Jew outlet. Fly and the Fly-Bottle is dedicated 'for William Shawn', who was a long-term editor who 'oversaw the magazine's coverage of World War II'. It ran a propaganda piece on Hiroshima, by John Hersey, in 1946. So it's pretty certain that Shawm would only run the Jewish view, and I looked for this in Mehta's book. I have no idea whether Mehta had any knowledge of Jews.

• Some Background of the Time; 1945-1965.

In about 1945, Kierkegaard and Sartre (Jew) were being pushed. Both were 'existentialist', in theory opposing planning, thought, rationality etc. I don't know if Kierkegaard was Jewish; probably. Karl Popper's Open Society and its Enemies was first published in 1945, rather absurdly amid remote mass rapes and slaughter. At another level, Hitchcock's Rebecca was popular (and led him to Hollywood, and faked concentration camp movies). And the vast money-making and Cold-War-simulating nuclear fraud was building up.

The CIA was officially established 1947. Encounter was an 'intellectual' thing of about that time. So was Commentary, 'a leading postwar journal of Jewish affairs.' At the time, the BBC's Listener was more Jewish junk—at the time, the BBC was mostly radio. Later, the BBC produced The Spectator.

By 1962 and 1963, with color film, Jew rubbish was flooding the world: The Sound of Music and Dr Zhivago are examples. The Beatles and others, with vinyl records, provided very light relief. Karl Popper's Conjectures and Refutations (1962) aimed at a theory of science giving a central position to disprovability. Naturally, real-life practical science was not amenable to such simple descriptors.

• Four pages which I recommend, but can be skipped:–

• 1 Jew emigrants in England (Perry Anderson 1969). Fascinating as giving the Jewish viewpoint. He ignores the great majority of Jewish infiltration into Britain, and of course ignores the long-standing presence of Jewish banking since Cromwell.

He suggests inter-war Jews who came to Britain and became well-known were different from Jews in the USSR, who, though Anderson doesn't say so, were mostly explicitly murderous. Interesting lists of their names: Wittgenstein, Malinowski, Namier, Popper, Isaiah Berlin, Gombrich, Eysenck, Melanie Klein, Deutscher. And Kaldor, Sraffa, Gellner, G R Elton, Balogh, Von Hayek, Plamenatz, Lichtheim, Steiner, Wind, Wittkower. They contributed little to long-term thought.

All the while, it's fascinating to sense the way argument is pushed away and discouraged—many interesting topics are evaded, and unimportant material inserted. Marx is not analysed; Jews are unmentioned; Popper's Conjectures and Refutations says nothing about practical science; the Jewish money monopoly of the 'Fed' isn't mentioned; people like Joan Robinson are lightweight fellow travellers; Jewish Communism, and its allies, are completely suppressed.

• 2 Miles Mathis on Wittgenstein and others. Interesting on Jews in Austria-Hungary before WW1. And the Wittgensteins as hugely rich. Ludwig Wittgenstein seems to have been in the same class in school as Hitler. Many people—not in Oxford, though—commented on Wittgenstein's obscure philosophy as Jewish influenced.

• 3 Miles Mathis on rich Indians, in particular, Gandhi as a project for Britain in India, as Jews worked for war. There's some mention of other Mehtas, but I don't know how relevant (if any) they are..

• 4 H G Wells Mind at the End of its Tether (1945) shows Wells succumbing to despair. His nationalist mental equipment did not grasp Jews as international fragments, colluding with secretive national local groups. World-wide networks of Jews—in contrast—including Churchill, Roosevelt, Hitler, Stalin—took such arrangements for granted. But Wells could make no sense of the Second World War. Nor could most people. And Jews worked very hard to ensure this state of affairs persisted. It still does for very many unwoken 'sheeple'.

More scraps of information on Ved Mehta

Mehta was born into a Hindu family in Lahore in 1934. India was partitioned after the Second World War in 1947, when Mehta was 13: his family "lost everything". 14 million are said to have been 'displaced' either to the new Islamic states or to India. Islam was originally a Jewish invention; probably post-1945 Jew ambitions had something to do with all that.

Ved Mehta went to 'various schools in India and America', obtaining 'degrees from Pomona College, ... Modern History at Balliol, and Harvard'. He thinks (from an interview) Proust's novel one of the greatest ever written. He hated the Oxford cold, quite liked the gowns, disliked the class distinction in three lengths of gowns. He showed signs of a Hindu outlook: it is a "sign of maturity when one no longer worries what one's father would think. ... He wanted me to marry a white woman.. Hindus believe in karma.. my mother .. a Hindu woman.. would probably think blindness was .. karma.. punishment for previous deeds.."

His 1965 book The New Theologian was possibly sparked by John Robinson's 1963 book, Honest to God. My notes assume the Jewish forgeries aspect of Christianity were unmentioned; and the post-1945 Jewish fraud of attributing mass slaughter to Germans, but not to Stalin and Mao and Roosevelt, would be upheld; and the eastern forms of Christianity would also not be mentioned.

• Part 1: Ecce Homo looks at Jesus, of course in an unskeptical way. Paul Tillich being Protestant, and Reinhold Nieburgh 'Professor of Applied Christianity'—only in Jewish USA!

• Part 2: The Ekklesia tries to describe established churches, without discussing lands and money and violent 'conmversions'. Vidler; Ramsey; John Robinson of 'Honest to God'; Rudolf Bultmann.

• Part 3: Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer was 'a controversial figure in his Church for his part in the plot to assassinate Hitler.' Naturally the main part of Jewish propaganda; adds to the suggestion that Mehta was, or felt he had to be, conventional in his writing.

• Index notes 16 double columns including: Aquinas, Karl Barth, Cambridge movement, Canaris, Canterbury Tales, Death of God, Demythologization, Fichte, Flossenburg concentration camp, Goethe, Harvard, Tubingen, The Men who tried to kill Hitler, University of Chicago Divinity School, Vidler.

John is Easy to Please (my notes say 1962-1971; 'Encounters with the written and the spoken word'—more New Yorker stuff). Must have been part of the Chomsky 'revolution', though Mehta evidently made neither head nor tail of phony Noamie. Much of the material was on George Sherry, famous at the time as 'the U.N. interpreter'; written about 1961; after 'a senior officer in the Office of the Under-Secretaries-General for Special Political Affairs'. An American: read: Jew. Mehta gives an account of the shift from 'consecutive interpretation' to 'simultaneous interpretation' (without which 'the UN would have to quintuple its meeting time'). On careful reading, it appears Sherry simply noted a few keywords, then made a verbose speech resembling the original (and substituting e.g. Macbeth for Pushkin (in a speech on Greece, Bulgaria, Albania), or the Cheshire Cat's grin for some Russian fable. With a longish biography—a bit like Ustinov's—family background (plenty of money, piano playing and songs, books, suggestion of Jewish exclusivity; going to Poland, Vienna, Bucharest, life in flats etc, tutors, hates eastern Europe of course). Includes Tanganyika as a new member; and stuff on Olduvai Gorge.

The Third (1971 endnote) is a letter possibly composed or edited by Mehta on Philistines etc and the 'Third Programme', a BBC radio wavelength becoming 'a historical record of a cultural phenomenon..'; it was cut from 6pm to midnight to three hours per day (extended a year later to a couple more hours on Saturday) '.. the intellectual élite, who were supported by the rule of an aristocracy, are being relentlessly destroyed by Philistines who are supplanted by petit-bourgeois bureaucrats..' There's more here, suppressed as it's 'cultural', not intellectual.

• At last! Contents of Fly and the Fly-Bottle

In sequence, the main interviewees are, in Philosophy: 'John'—a real or perhaps supposed friend from Oxford, brought up on Latin and Greek, living in a Chelsea basement, providing something like a continuo. Gilbert Ryle (of The Concept of Mind, Ernest Gellner, Bertrand Russell, all in London. Then Oxford: Richard Hare, A J Ayer, P F Strawson, Iris Murdoch, G J Warnock. Then back in London with Stuart Hampshire. Dead persons, included with numerous descriptions, included J L Austin, Wittgenstein, and Namierowski.

In Modern History: Hugh Trevor-Roper [=Lord Dacre], A J P Taylor, Toynbee, Pieter Geyl, E H Carr, C V Wedgwood, Christopher Hill, R H Tawney, John Brooke, Herbert Butterfield, and the widow of Lewis Namier.

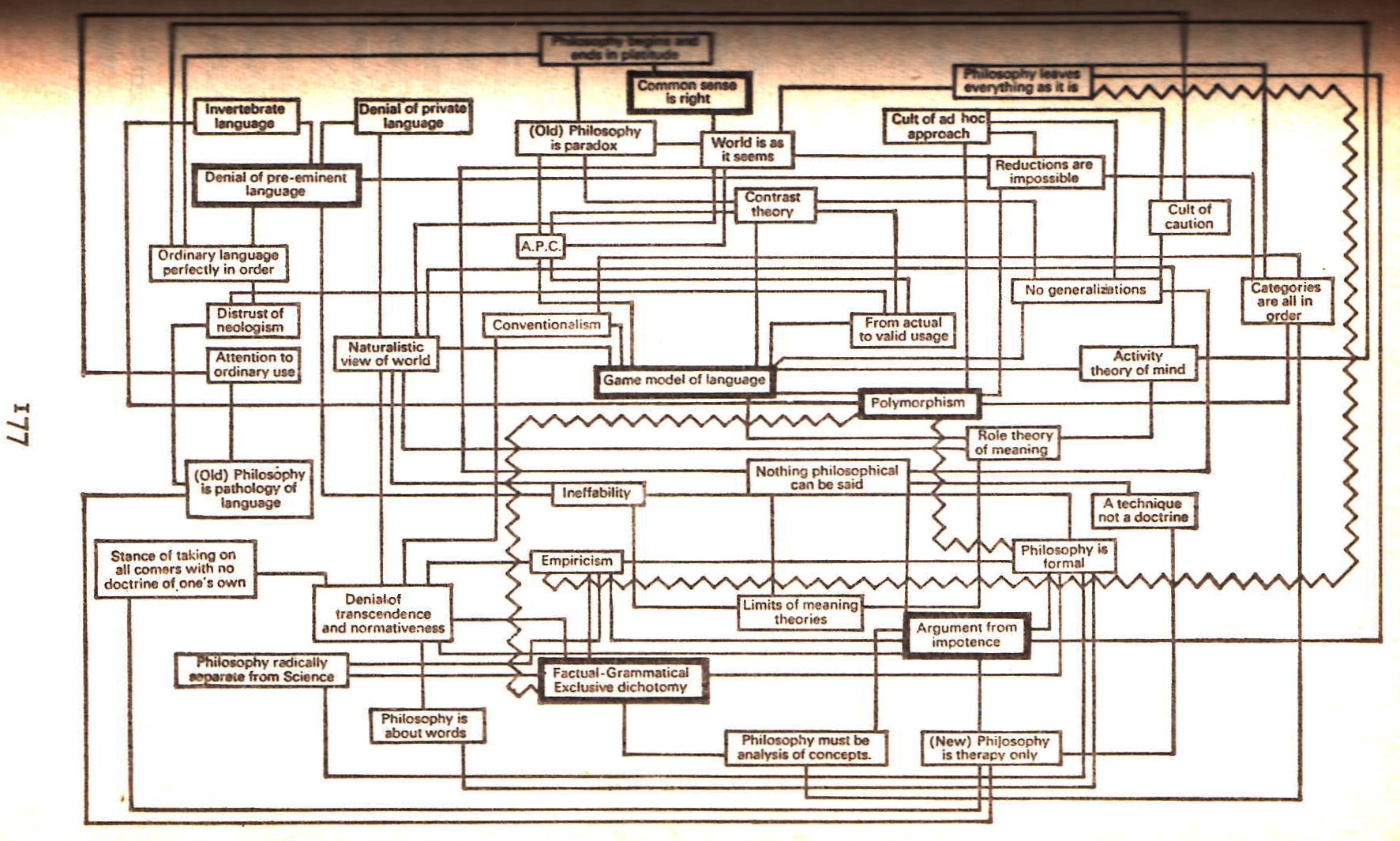

I have some detailed notes on Fly and the Fly-Bottle, but the can't be summarised. As examples, the first part ('A Battle Against the Bewitchment of Our Intelligence') starts with a 'Review refused' letter in the Times, 1959, by Russell, on Prof Ryle's refusal to allow a review of 'Words and Things' in 'Mind'. Mehta 'recalls' Gellner was Reader in Sociology at the LSE, and Gilbert Ryle Wayneflete Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy at Oxford. More letters appeared: Gellner on the method being inherently evasive (see the diagram below!), the private solicitor to the Queen on power of ridicule, B F McGuinness on the charge made against [cardinal] Newman. Undergraduates were assumed to support 'abusiveness', regarding two books by Russell, and one by Gilbert Ryle, as 'classics'. A Queens Council said things on blunt criticism, and Socrates. Russell said Nietzsche called John Stuart Mill a 'blockhead', in a '.. serious piece of philosophical work'. There were editorials in the Times and the Economist.

During all this, Mehta, in London, wrote to 'three or four philosophers' and approached an old Oxford friend .. trained in Latin and Greek since the age of six.. I'll call him John.. Greats men.. Wittgenstein, Ayer, Strawson, Hare, P H Nowell-Smith [who was a compulsive impregnator of students].. articles in Mind and Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society.. exam questions: "Is my hearing a noise in my head..?" "Who is Socrates?" "If I know that Y is the case, is it possible for me not to know that I know it?" .. The idea of Greats' philosophy is that after a few years .. the high-powered undergraduate can unravel any sort of puzzle more or less better than the next man. It makes a technique of being non-technical...'

Mehta visited Gellner, in SW15. He'd been been lectured to by Austin, and didn't like him. And visited Russell, in his house in Chelsea; this was in Russell's post-Cuba nuclear war period, but before his Vietnam War activity. Russell is quoted as saying: "Oxford and Cambridge are the last medieval islands - all right for first-class people. But their security is harmful to second-class people - it makes them insular and gaga. That is why English academic life is creative for some but sterile for many." Russell never understood Jews. Or the influence of Oxford as a meeting-place for moneyed gangs. Russell thought the Universities were rather independent: Bertrand Russell's America (vol I) says universities, like the church, had hard-won independence from the state in the Middle Ages. Which shows how wrong you can be; it's about as true as saying the BBC is 'independent'. Or the 'Church of England'. It's truer to say that Oxford was largely established in support of the Jewish invasion, or infiltration, of the Bank of England following the decision to change from the Netherlands.

It's a fascinating picture: intellectual hooks, evolved to snare people into wasting their lives, but of course getting paid for it. It's difficult to resist the idea that all so-called philosophy was and is elaborate time-wasting, combined with careful evasion of important issues.

• Fly and the Fly-Bottle is online here (that's the pdf format; and there are plain text versions) which I recommend as paper copies are likely to be fairly rare. The title is taken from a comment by Wittgenstein, itself possibly from some antique Talmudic source.

• Oxford University as post-Jew Infiltration Propaganda Source

Up at Oxford (1992 book by Mehta)) included parts from his book, on historians. It interested me in its great detail—the usual careerist types, like Clive James, are obviously not interested in their subjects, regarding the as tedious obstacles which in any case are hard to judge, since for example Anglo-Saxon is so remote. A byway is the promotion of people for political and money reasons—an oil Arab or (((Arab))) donor getting his son in, a lecturer in electromagnetism given a post only because it was open, 'Gerald Fleming' of audio-visual equipment awarded a Chair of 'Holocaust Studies', A J Ayer given a first class degree after frantic discussions on his disappointing final exam.

Oxford by Jan Morris, not Mehta, is an eclectic book including the University, and says 'there is no person or body in Oxford.. competent to declare what the functions of the University are. The University Statutes .. run to 700 pages..' Academic freedom isn't part of their constitutional set-up. The Regius Professor of History was invented to supply Henry VIII with intellectual ammunition against the Pope and anti-monarchists. Jews, Catholics and women were excluded until relatively recently, at least nominally: sceptically-minded types may notice symbiosis between the Church and various Jewries. Since Cromwell, explicit discussion of Jews has been effectively banned. Jews entering England as a post-Napoleonic 'aristocracy' is a topic that has been severely censored; Cobbett is one of a thin rivulet of honest commentators. The mediaeval appearance of Oxford hides strict adherence to contemporary world-views. Scotland is known for never having expelled Jews.

I attempted an examination of Regius Professors—Oxford, Cambridge, Dublin, and so on; Divinity came early; Medicine in 1546; Greek, Hebrew, and Civil Law; Modern History (Cambridge, 1724); but careful cataloguing did not reveal an unchallenged pattern. Though no doubt there was one.

Geoffrey Bindman (b. 1933), who became part of the Jewish 'human rights' industry, went there to study law; and thence to the 'Race Relations Board', Private Eye, Amnesty International, and South Africa's Apartheid system. And Oxford seems to be reaping its reward for its many centuries of indolence: now, 25% of admissions are reserved for people that Oxford admits are not qualified to be there and for whom the university will have to finance at least one year of remedial education if they are to have a chance to graduate.

Cambridge University is also cleansing itself of racists. Gonville & Caius College is removing a window that commemorates Sir Ronald Fisher, Fellow of the Royal Society and former president of the college. Fisher is considered to be a genius who almost single-handedly created the foundations for modern statistical science and is regarded as the single most important figure in 20th century statistics.

I have some old press cuttings of Toynbee (and Spengler, and others) from the Listener and Times Literary Supplement, dated 1947 through 1965, mostly the 1950s, conveying a saddening feel of comfortable elderly males, salaried and pensioned for life, talking about things almost disconnected from any life. But there are occasional jousts over such items as Scramuzza on the slave revolt in Sicily in 133 B.C. and a hypothetical revival of cultivation of wheat, and the first Punic war is always written by Toynbee as "the first bout of the Romano-Cathaginian War".

Toynbee liked the classics, but also met Hitler and was supposed to be an authority on the Treaty of Versailles. He liked the 'Great Man' theory, but the version where great men were not seriously hunted. His list of names includes saints, Lenin, Mohammed. The RIIA is part of the Jewish intrusion, and of course the books' dates conform to the Zionist Jew Hitler view of the 20th century. Mein Kampf and A Study of History form something of a pair, neither looking at money interests. If you're in a mood to dabble in universal history, which however fails, these volumes deserve a scan.

I hope, and sometimes allow myself to expect, that serious historians will arise who reshape categories into forms from nature.

• R H Tawney

Tawney (1880-1962) was famous for Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (published 1926, but based on 1922 lectures) seems to have been Anglican, a Christian Socialist, and close friends with Archbishops. He is not included in Mehta's interviewees. He was influential in the sense his books were read. But (of course) he says nothing on Jewish money—none of these people seem to have noticed the Federal Reserve, even including J M Keynes.

An interesting aspect of Christianity is its supposed banning of usury, which in my view served simply enough as a way to preserve the Jewish monopoly on lending. It was a symbiotic way to exploit ordinary people, though guilds and Freemasons and vicars and others provided for some leakage.

Here's a downloadable version of Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. An irritating feature is his failure to say what 'capitalism' is—naturally, something keenly desired by Jews.

His book only deals with the 16th and 17th centuries and has little on wars, and little on industry. His contents list is:

I The Mediæval Background | IL The Continental Reformers | III. The Church of England | IV. The Puritan Movement | V. Conclusion.

It's a safe deduction that most of his target audience found little of use on modern life and on the First World War and the 'Russian Revolution'.

• Herbert Butterfield

1900-1979. Herbert Butterfield was a perfect example of feeble historical analysis; no wonder he became Regius Professor of History (at Cambridge). He wrote about twenty books; his main books are reported to be The Whig Interpretation of History (first published 1931), The Origins of Modern Science (first published 1948) and Christianity and History (first published 1949). Some of his other books may be useful; but it seems unlikely that they could be, or that anyone would read them.

His Christianity and History starts: 'THE God who brought his people out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage, was to be celebrated in the Old Testament pre-eminently as the God of History.' The nod to the King James Version demarcates Butterfield's limitations. No wonder Jews laugh at whites! He notices that many things are missing: '... the Marxists... in spite of uncouthnesses... have contributed mote to the historical scholarship of all of us than the non-Marxists like to confess ... they have appropriated truth which are dangerous in the hands of anybody except a Christian.' Butterfield was so far from anything like historical science that I suppose it's best to ignore him.

His book on the origins of science looks at separate issues, clearly taken from other sources. Impetus (I suppose his look at mass, velocity, and so on, but omitting the more complicated stuff); the heart (based on Harvey); Bacon and Descartes; gravitation; chemistry (notably gases such as oxygen and nitrogen; evolution; other things. He has no maths. And something more hard to describe: the control and ownership of science. Historians tend to be funded, and dislike discussing ownership of their ideas; and so do scientists. And Butterfield doesn't have enough grasp to project into the future: DNA and digital transmission, though imminent, are out of his range, or one might say off his radar.

His sources are not given—probably he had little idea how much doubt there was, for example about Newton and Darwin. However, he gives suggestions for further reading, and includes Humphrey Pledge's excellent book Science Since 1600, Burtt's book on philoosophical foundations, which comes near to saying Christianity led to science; some standard histories: Dampier, Singer, Johnson, Sherwood Taylor; Kuhn starting to go; no Popper; Whitehead trying to be philosophical; but not original research.

• Ernest Gellner

• Gilbert Ryle

Dilemmas (1954) e.g. The World of Science and the Everyday World, Technical and Untechnical Concepts. I wonder if he ever suspected that the films of 'nuclear weapons' were fakes. The Concept of Mind (1949). My paperback copy is inscribed, in Italianate handwriting, with a name, and the University of East Anglia.

• Pieter Geyl

Geyl was Dutch, and spent some time teaching in Britain. He had a heavily-promoted paperback—thick paper, large format, full-colour cover, a 'Peregrine'—and was clearly thought slightly important. A J P Taylor praised him for some observation on an army getting as far as a river, but no further. The Netherlands had importance because of their transmission of the Jewish debt system to England, then the USA, accompanied by various wars. But this is not in Mehta, who took the trouble to visit Utrecht in search of an interviews. I tried to review Napoleon: For and Against but it's a sort of clippings album by people without insight into either the French Revolution or Napoleon.

• Stuart Hampshire

Spinoza (first published in 1951, apparently by Penguin books; the cover has a curious modern imitation of an engraving). The blurb says Hampshire was born 1914, 'educated at Balliol College, Oxford, elected a fellow of All Souls in 1936. Served in the army etc. All the propaganda books of the time automatically note the service in the Second World War. Part of the promotional path is to assume there was no option but war, though it's not even stated. Rather laughable that supposedly eminent moral philosophers should have nothing to say on such a subject. Wiki states that he enlisted, but went into intelligence, and worked in London 'with Oxford colleagues such as Gilbert Ryle and Hugh Trevor-Roper'. The latter wrote The Last Days of Hitler, of course saying nothing analytical about the war, and ignoring the role of Jews in both world wars. Hampshire of course determining that there was true evil in Nazi officers.

And the same thing is true of the subject matter. Here, as would be expected, it's such things as 'God' and Talmudic material, camouflaged deeply. Here for example appears to be the ghostly presence of the 'kol nidre': '... he is more consistent [than Hobbes] in refusing to attach any meaning to the words 'right' and 'duty' in their purely moral sense; he is more consistent in regarding the laws and conventions of a society or state as deriving their authority and claim to obedience solely from their usefulness in serving the essential interests of the individuals concerned; as soon as a particular law or convention ceases to safe guard, or begins to threaten, the safety or happiness of a particular individual, that individual is thereby released from any obligation to conform to it; the mere fact that he had previously undertaken to conform to it does not constitute a binding obligation which overrides his personal needs and interests; for nothing can ever, either in principle or in practice, override these needs and interests. ...'

It's saddening to think of the unfortunate students faced with such smeary opacity. Especially when the cover says 'This book is a model of its kind.' Spinoza of course was important to Jews, keen to pretend they had produced stellar intellectuals. There's some fascination in tracing Jewish patterns in these people, but life is too short to wade through such junk.

• A J Ayer

The Problem of Knowledge (first published 1956, in Pelican paperbacks, of course a Jewish publisher, evidently aimed at the new mass production philosophy departments, which Ayer was very keen should be expanded). It has five sections: I PHILOSOPHY AND KNOWLEDGE, 2 SCEPTICISM AND CERTAINTY, 3 PERCEPTION, 4 MEMORY, 5 MYSELF AND OTHERS.

Ayer was born in 1910 in St John's Wood, in north west London, to a wealthy family from continental Europe. His mother, Reine Citroën, was from the Dutch-Jewish family who founded the Citroën car company in France. His father, Jules Ayer, was a Swiss Calvinist financier who worked for the Rothschild family. He spent a year in Vienna; part of the 'Vienna Circle'. In the Second World War, which of course he seems to have had no qualms about, he served as an officer in the Welsh Guards, chiefly in intelligence (Special Operations Executive (SOE) and MI6.

One of the most important, unaddressed, philosophical problems in knowledge is the way in which the senses can be intercepted and controlled; language, alphabets, writings, and modern developments such as mass publishing and broadcasting. And of course there are questions in the sort of thing called 'brainwashing'. Presumably Ayer had wartime experience, but if so he said nothing. Of course he said nothing Talmudic, for example on the way practices are carried on through centuries. He had various professorial posts, generally with ancient and venerable-sounding titles. Sigh.

An interesting issue is power, supplied by knowledge. Consider Jewish bankers around the world: we ordinary types have some idea of the status of assets—say, houses, shops, and farms, and factories. A vague idea. Imagine the power of having information of great swathes of urban housing, shops, suppliers, transport. How could they possibly neglect the possibilities of manipulating their underlings and inferiors?

• G M Trevelyan

English Social History (from the Penguin British edition) was first published in the USA and Canada in 1942; then Great Britain in 1944. It's obviously a propaganda documents; in fact the 4-volume set deserves study in that light, though of course it's only a tiny part of the enormous wave of propaganda. Let me just list the undiscussed material: nothing on money; nothing on the way land was parcelled out, and the violence used in the supposed conversion to Christianity; nothing on secrets; nothing on skills, techniques, records. And at another layer, plans, changes, intentions, and plots. Trevelyan (he may have got his 'Order of Merit' for this) seems to have caught a mood, in the same way that presentations of quaint illustrations and rural English scenes curtained off the facts of international money and industry, rail, airplanes. Sad stuff; not even true to its supposed readership.

• A J P Taylor

A J P Taylor fellow traveller. My account of Taylor's life: promotion from nowhere to unqualified pundit on wars.

Review of Origins of the Second World War.

• E H Carr

Carr's book What is History? (1961; free online) was in the early 60s era in Ved Mehta's slender volumes of reportage.

Carr's A History of Soviet Russia. The Bolshevik Revolution 1917-1923 is Penguin Books paperback edition of E H Carr's series of books, published in 1966. E H Carr (1892-1982) is described by Wikipedia as a 'historian, diplomat, journalist and international relations theorist'. Of course he was. It's a saddening experience to read, or at look through, this stuff, embellished perhaps by reviews snipped from the junk press (Bryan Magee in The Times, Julian Symons from somewhere). I haven't bothered to check how much of Carr's projected series was written or published. Carr spent some of his life in Hampstead, perhaps inevitably. He gives some prefatory matter, with the usual rather embarrassingly effusive thanks. Volume 3 has a bibliography: Committees, Laws, Party Documents, Proceedings of this and that, works by Lenin, Marx, and the rest. Nothing accurate on Jews, Jewish money, payments for such things as arms and ammunition, communications with New York Jews and financiers. More propaganda, aiming for the taking-over of Russia and its empire, in effect paid for by that same process.

•Winston Churchill

March 1948 was volume I of 4 volumes of The Second World War. The Theme of the Volume in his Tolkien-like (or more accurately Macaulay-esque) language is: HOW THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLE THROUGH THEIR UNWISDOM, CARELESSNESS AND GOOD-NATURE ALLOWED THE WICKED TO REARM

'One day President Roosevelt told me that he was asking publicly for suggestions about what the war should be called. I said at once "The Unnecessary War". There never was a war more easy to stop ... after all the exertions and sacrifices of hundreds of millions of people and of the victories of the Righteous Cause, we have still not found Peace or Security...' Churchill doesn't say how it could easily have been stopped, but perhaps the clue is in Freemasonry: ... British Colonel John C. Scott ... gave an election speech on August 14, 1947 [and] revealed the real underlying issues of the World War II. Scott claimed that at the conclusion of military operations in Poland a war by telegram was waged between the Allies and the German Foreign Office. He was one of the transmitters in those negotiations. The Allies gave the Reich two conditions, and their acceptance would have brought about an immediate cessation of hostilities, and a free rein for Germany in Poland. Those conditions were, Germany must return to the Gold Standard and the League of Freemasonry must be readmitted to Germany.

According to Wikipedia, the official British History of the Second World War was started in 1949 and finished in 1993, and sold by HMSO. For revisionist critiques of these events, I recommend Hexzane527 of France who dissects in bite-size chunks the military events.

He was right about the unwisdom.