Review of Shakespeare/ de Vere Controversy J T Looney: Shakespeare Identified

Review of Shakespeare/ de Vere Controversy J T Looney: Shakespeare Identified Pioneering revisionist Shakespeare work, with surprising implications, June 24, 2011

Pioneering revisionist Shakespeare work, with surprising implications, June 24, 2011Looney's double-o is for emphasis, in some languages, e.g. Dutch, as in 'brooch'—everyone points out he isn't pronounced to rhyme with 'loony'. This book was published in 1920, after some years' work. It's not the first alternative authorship book: in 1910 for example a Baconian work was published. Looney is always described as a schoolmaster or teacher in Gateshead (a town on the other side of the Tyne from Newcastle), though so far as I know, no school in the area claims him.

Looney's method was to comb the plays for clues as to character, then comb what's known of the Elizabethan world for a person to match, detective fashion. It would be inaccurate to state that controversy raged thereafter. He was largely ignored and shrugged off. But he must have made a bit of impact, since one volume of Galsworthy's Forsyte Saga mentions the theory.

This book therefore has some historical significance. Just a few notes:

[1] It's a tremendous proving-ground for theories of revisionism. Every possible attitude—derision, contempt, accusations of ignorance, etc—and every possible style of counter-argument—pulling of rank, ridicule, concentration on trivia etc—has been used against Looney, and, for that matter, by his supporters when on the defensive.

[2] In principle, deletion of the 'Stratford man' (probably an illiterate war profiteer in food) should allow a far better appreciation of the Elizabethan period. This means historians would have to do some hard work, however. (One edition of this book included an excellent description by Capt. Ward of England as engaged in a war with Spain, comparable with the First World War, and far removed from the ahistorical merrie England stereotype of for example 'Shakespeare in Love').

[3] What does it matter?—Well, there's an effect on educational theory. Occasionally , educators look at the real world, and even more occasionally, at genius. Their view of 'Shakespeare' therefore is of some importance. If the traditional story is correct, genius can appear anywhere, even to someone of little education, who is thought to be able to deduce almost everything about the world. But if Looney is right, education is of paramount importance. Present-day acceptance of poor educational standards therefore owes something to the 'Shakespeare' myth.

________________

I haven't seen this paperback, which I assume is a straight reprint of the 1920 book, 1920 typography and all.

Looney struck lucky—on his quest he found just one single published poem by Oxford, 'Women', which conformed to his checklist of characteristics. This was the clue which he followed up relentlessly.

There's a two volume American edition of 1975, edited by Ruth Lloyd Miller, which of course has added material—including a good piece by a Captain Ward, pointing out that there was war with Spain at the time and that as a result there was widespread poverty, famine, and high food prices. The 'merrie England' stuff as in 'Shakespeare in Love' is fantasy. Miller's volumes are lavishly produced with may monochrome and colour reproductions of portraits etc.

However; I do have something of a warning. De Vere put his own life story into his plays and sonnets. As you come to understand 'Shakespeare' it becomes clear that de Vere was an aristocrat obsessed by his own sidelining—he was a monstrous egotist. His work describes Elizabeth's court with unsparing accuracy, but beneath it all is an aristocratic world view with no room for the masses—unless they are amusing writer/actor types.

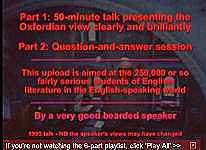

A further point: the 'Shakspere' mythology has been guarded by a ridiculous corps of professional careerists. To this date, this still applies, though possibly the USA is shedding this absurd skin more successfully that Britain. However, a similar pattern is appearing amongst the Oxfordians, who have their own ring of paid journals and publications and speakers. I tried to get a 50 minute speech by Burford/Beauclerk on Youtube, to help diffuse the message more widely. He didn't want it up there, possibly on copyright grounds, or because he considered it lacklustre, though in my view it was an excellent introductory overview. Most of the content was Looney, paraphased.

Here's a 6-part talk presenting the Oxfordian case; right-click to watch in Youtube:--