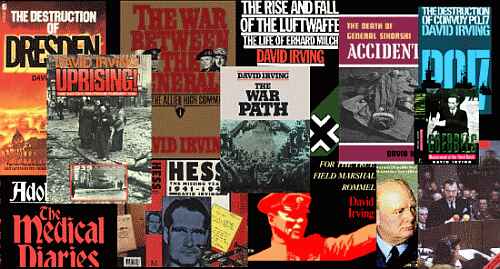

The War Between the Generals by David Irving (1981). Cover not illustrated.

Review: 'Rerevisionist' 4 March 2018

Entire chains of missing links

One of the obvious conflicts, now—much bigger than a 'hairline crack'—was between Patton and Jewish and crypto Generals. Patton (and Forrestal of part of the US Navy) are mentioned, but treated lightly. It's even possible that the subject was suggested as a diversion away from inquiry into the subject.

-RW

Irving's sources: largely Eisenhower archives in Abilene; the PRO in Kew, London; and Washington D.C. archives, plus diaries, as partly listed in his 'Acknowledgements'. (Many diaries were new to historians: some locked away privately, some officially censored, some inaccessible, some illegible.) Three 'initial legwork' people were Nicholas Reynolds in Washington, Charmaine Henthorn in Ottawa, and Venona Bryan in London. And other colleagues and interviewees helped. Note that the time spent by Irving is not stated; it's impossible to guess how long he took reading archives and diaries and transcripts.

Although this suggests a great deal of work, a great deal is omitted, and the possibility exists that, all the time, Irving was a crypto-Jew, and took the appropriate line. This book was published 35 years after the war ended, arguably more than enough for tougher revisionism. Perhaps his 'editor and publisher' Thomas B. Congdon Jr. had some influence. However, it may have been a natural progression away from Jewish censorship: Irving's Uprising! on Hungary in 1956 unquestionably introduced Jewish issues, and was published in the same year, by other publishers, as far as I've checked. In view of Irving's later legal challenges to the crypto-Jew establishment, the natural progression alternative seems likelier to me.

The War Between the Generals ('Inside the Allied High Command') deals almost entirely with western Europe; the Allied Expeditionary Force and 'Omaha' Beach and approach to Berlin looming large. There is virtually nothing on Stalin's Jewish mass murdering empire, and little on eastern Europe—a bit on Yugoslavia, a little on Scandinavia. Though of course they had generals, too.

And very little on supplies and costs, for example oil. There are hardware sidelines: the artificial harbour(s), code named Mulberry, get a few mentions; the 'pipe line under the ocean' (PLUTO) none. The tanks fitted with canvas skirts, to keep them afloat, seem to have failed. The V1 is discussed, starting with the aerial discovery of large concrete ramps. In view of the primacy of bombing, with its numerous advocates, it seems odd that flak and air defences weren't boosted, but perhaps I'm underestimating them. Presumably Generals had opinions on such things.

It's all at a rather trivial and gossipy level, rather like a 'soap opera' with characters with stars on their caps or helmets. Kay Summersby (Irish shiksa driver) and Eisenhower, and other mistresses play their parts. Hotels in London and Paris play some part; I wonder if hoteliers looked back on the time in the way Jews do the Weimar republic. The vast number of Americans in the UK—something like three quarters of a million—and social contrasts get Irving's attention, but he doesn't consider (for example) why they were paid more. But the Generals' dislikes remain at a rather piffling level, since possible important differences are not explored. I suspect Montgomery was permitted because of his total lack of Jew-awareness. Generally, all the material not taken from written sources is filled, even if unconsciously, by controlled propaganda.

(P.400) Eisenhower decided unilaterally to wait for Stalin—very likely following a Jewish policy. ‘As the noted historian Sir Arthur Bryant would later write, the British were thus forced to witness "at the dictate of one of their principal allies" the needless subjection of the whole of eastern Europe to the tyranny of the other [sic] ... Huffed Brook ... "he has no business to address Stalin direct, his communications should be through the Combined Chiefs of Staff; ...’

Irving writes: 'Kansas plainsman Eisenhower feared no Russians—... he felt that in their generous instincts, in their healthy, direct outlook ... the Russians bore a marked similarity to the average American.' Errrrmmm.

This sort of thing is worrying, since the ubiquity of Jewish secret working is unmentioned or unknown by Irving. (He describes Baruch at one point as a 'philanthropist'!) There are many questions: for example, how differently was presumably Jew-aware anti-Freemason Vichy France treated from the rest of France? Who place de Gaulle as a potential leader? (Irving notes de Gaulle's rather absurd self-centredness, but provides no background). Irving is unaware of Patton's murder, and Forrestal's, and no doubt others. He has nothing analytical on Roosevelt, or Churchill, or (later) Truman.

Irving gives plenty of examples of wartime censorship, and censorship after the war, usually I think face-saving matters. Note incidentally that Irving says nothing about Montgomery's rather obvious homosexuality—at least, as far as I know, being accompanied by a favourite young man. This gives some idea of the potential censorship even of not very important private matters. Irving says almost nothing about the notorious Hungarian Jew propagandist, at the BBC, Brendan Bracken, and other propagandists.

Irving interpolates his own views of character, which of course is hard to avoid in a world saturated with propaganda. He is impressed at second-hand by Stalin; it doesn't seem to occur to him that Stalin had full access to Jewish spy information, and could hardly help appearing to be penetrating, just as a colleague of Lenin said Lenin's predications were right about ten times' I think he said. Irving views Eisenhower (pp 10-11) as top of his class from the Army Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, and with an 'extraordinarily rigorous' code of honor. The James Bacque school of thought did not exist in print at that time, at least in Britain. Continentals were better informed.

As to weaponry (e.g. p 201) there are confusing reports, for example on Panther and Tiger tanks, mostly saying they were better, though one says the opposite (a typo?) and a New York Times comment, which for all anyone could tell may be Jews wanting more profit from weapon factories.

I don't think this book has worn well. I suppose revisionism is inevitably slow and erratic, and needs many contributors.