Review of James Hamilton-Paterson Empire of the Clouds

Review of James Hamilton-Paterson Empire of the Clouds

'When Britain's Aircraft Ruled the World'. Mostly about Test Pilots. Not much on the real world of war, money, and people. This review August 18, 2014

'When Britain's Aircraft Ruled the World'. Mostly about Test Pilots. Not much on the real world of war, money, and people. This review August 18, 2014SIMPLETONS IN THE SKIES: LONG REVIEW WARNING!

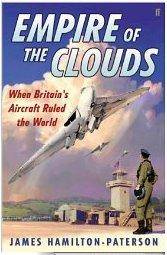

Published by faber and faber [sic - no capitals], who are more associated with poetic and supposedly artistic books and novels which some people feel they ought to read. Perhaps this choice is explained by the same author's published list in 2010: fiction, children's fiction, and poetry, plus six non-fiction titles, mostly not connected with world wars.

Each chapter has endnotes: the sources are test pilot memoirs, surveys of test pilots of fighters and some bombers, magazines (e.g. 'Flight'). Plus interviews, notably with Bill Waterton's surviving family and friends, Richard Bentham, and John Farley. Waterton's voice survives in tape(s) by Bill Algie. 'The World's Worst Aircraft' is referred to a few times (edited Winchester, and a source for aircraft liable to crash)..

The book has a detailed index, longer than the notes, perhaps computer-generated: all the planes are listed, with their variants (Mark I, II, etc), and the manufacturing companies with their shifting names, the variants usually caused by amalgamations. So are engines. Whittle, test pilots, some politicians, special fuels (avpin and AVTUR are listed by name). But 'kerosene', 'fuel', 'crashes', 'designers', 'real costs', 'Edwards Air Force Base', (previously 'Muroc Army Airfield', in the Mojave desert) aren't indexed.

The ten chapters have clever titles, often containing quotations which can only be understood after reading the book. I wish they wouldn't do that; but everyone does. The final chapter, 10, 'Not with a bang' refers to the ending of the British air industry, not Faber and Faber and T S Eliot's end of the world.

Illustrations are from assorted sources, some private. There are about two dozen, but seem to be fewer because most are similar compositions. Such is the spreading scepticism of the time, that some stock photos look fake to me: much easier to make precision photos under controlled conditions with a Rolleiflex, then scalpel out the image and paste it onto some scenic picture. Does the exhaust show refraction? Could four planes in diamond formation really be photographed at high speed, as pin-sharp pictures?

Misleadingly, the photos resemble a biography showing only 'salad days' photos. As the text makes clear, we might expect pictures of machine graveyards littered with (p 119) Meteors, destroyed jigs and assemblages and mock-ups of cancelled aircraft, roomfuls of designers at drawing boards, windtunnels, suppliers of kerosene. And for that matter bombed cities, napalmed civilians, and refugees.

Important technical omissions include two matters which seem out of range of the author. Nothing unusual; unfortunately this dumbed-downness is completely general. The first is simple Newtonian dynamics and the science of fuels and energy. Probably designers were very familiar with all this, but kept it from the public, and probably from financiers. One example: a plane which was capable of a very fast ascent - tens of thousands of feet in less than a minute. But its fuel consumption was so high that the aircraft had only another fifteen minutes' flying time. The calculations involving fuel and acceleration must be fairly rule-of-thumb and standard, yet there only bare hints.

Significantly only three pages of the book look at the practical details; taken from an interview with John Farley [pp 312-314] who sounds exceptionally clued up. Here he is on TSR2 [Tactical Strike/ Reconnaissance]: 'The spec.[ification] was for a very high supersonic, low-level, long-range delivery of a nuclear weapon: a plane that's got to fly very fast, very low, and a very long way. The only way to do that is to put a negligible wing on it, so you don't get any drag, and fill it up with fuel. .. The trouble with a negligible wing is your take-off and landing performance becomes negligible. ... And I didn't like the P.1154 ... The whole point of a VSTOL [Vertical/ Short Take-Off/Landing] aircraft is its operating flexibility.: it can fly from a field, a bit of road, the back of a ship... But you've got to moderate your exhaust gas velocity and temperature..'

Farley's extracts show the lack of insight typical of almost all techies. He clearly believed what he'd been told about nuclear weapons, now known to have been a hoax, certainly a hoax at that time. No doubt he was also anti-Germanic, believed Hitler started the war, thought Stalin was 'Uncle Joe', and favoured bombing Korea, Vietnam and other places.

Farley may as well introduce us to the second omission from the book, Hamilton-Paterson's inability to quantify the air industries in any helpful way. Is there some power:cost ratio, for example? Here's Farley on 'Cost Plus': '... The idea was that we spend money, we do research, we do development, we give you the receipts, you pay the bill - and then you give us a percentage on top as profit.' A ludicrous way to run an aircraft industry, Farley said. Maybe it's just me, but his description is so bad as to suggest the entire industry was kept in a state of confusion. As to what percentage of British industry was air-related, Hamilton-Paterson has nothing better to say than it's large, expensive, unsustainable, or whatever.

This book starts with some rather childish material, correctly identified by the author as resembling attitudes in The Eagle comic. Since the Wright brothers, it's been known that a big enough engine, attached to properly shaped metal, can fly through the air, the forward motion counteracting the falling motion. Hamilton-Paterson's descriptions of load roars and bangs testify to his admiration for airshows of the time: Jesus! Woooah!!! He assesses planes by looks: graceful, splendid, amazing, sparkling in the sun. The spectators are supposed to have an understanding of aerobatics: show-stopping 'falling leaf', 'Zurabatic' cartwheel.

The author's early life, in Kent, reminds me of David Irving's reflections on aerial battles in British skies, and the V1 and V2. I suppose much of the excitement is the dicing-with-death aspect: it's hard to imagine anyone thrilling to drivers testing new cars and noting down faults, and it's hard to imagine test runs of submarines being publicised. But death from the air is obviously possible, and such events in the 1950s were common enough: the 1952 Farnborough Air Show's crowds, influenced by David Lean's film The Sound Barrier (1952) and the anticipation ('new Elizabethans') of an exciting, if almost uneducated, new Queen, and the new designs such as delta wings, was [p. 35] ruined by 29 deaths when a DH100 crashed. In 1954, a de Havilland Comet (jet airliner) crashed. In 1956, '6 of 8 Hawker Hunters caught in fog in East Anglia ran out of fuel and crashed.' [p 124].

Anyway, many boys must have wanted to be pilots, displacing the earlier ambition to drive trains. There's a nice account, including slang, of a jet pilot readying himself [Pp 120-1]. A popular paperback isn't going to include elaborate accounts of instrumentation and control, but there are technical terms ('wave drag') and slang ('in the drink') to give atmosphere. The job, not very well paid, at the time was [p 98] to go faster, and otherwise stress the machine, until it was about to become uncontrollable.

During the Second World War, it's stated that the pilots considered themselves superior to mere designers—an insanely anti-Darwinian attitude, surely. Barnes Wallis is quoted [p. 82] as being shocked at fifty-three deaths on the dam busting attack on Germany. Generally, pilot deaths seem to have been taken lightly, just as German deaths were taken lightly. 'Post-War' Britain (in quotes; there were plenty more wars) had a huge air industry. Despite the supposed huge success in bombing Germany to nothing, the air industry's main concern seems to have been worry over job losses. The Attlee 'Labour' government continued [p 139] to pay, despite the huge debts incurred by the war. (Hamilton-Paterson maintains the media myth that Labour won 'by a landslide'; though I'd guess he's right to say that pilots generally didn't like 'Labour').

Conspiratorialists have considerable food for thought here. The main dynamic seems to have been Jewish influence in the Washington-London-Moscow axis, which pursued what it thought of as its own interest ruthlessly, demanding huge payments for having been saved, and demanding huge profits for war materiel, and doing everything to prevent the USSR's inhumanity and atrocities from becoming known. (The BBC at the end of the war was run by Gen Jacob; all the eastern European mass atrocities were covered up). The USA's Jews worked on what must have been the myth of nuclear weapons, to make more money and get control of the simple soldiery, and have more of the same with the 'Cold War'. A Rothschild during the war had access to all British inventions. Later, the tradition was continued as (e.g.) the M52 jet was cancelled by Ben Lockspeiser, and broken up, and the jigs and prototype destroyed; but the plans were sent to the USA. Two engine drawings (for the Nene and Conway engines, I think) were GIVEN to the USSR.

In Britain, the Labour government had already adopted, in secret, the Jewish policy to damage Britain by immigration (see e.g. Lady Birdwood on this point). Their money control was probably seen as immovable. They must have decided to wind down British industry. People like Denis Healey and Tony Benn and Harold Wilson, without an ounce of science between them, were part of this policy. And union leaders and others were secretly funded to do their damage. Hamilton-Paterson quotes from a description of a pilot's anxiety to return in time to allow stowage of his plane: otherwise just one minute would allow the claim of an entire overtime shift.

The designers thrashed around, hoping for future orders. There were conflicts between family firms, heads of families, teams of designers and lead designers. The company directors seem almost casually uninterested; there are amusing accounts of two-hour dinners every day with full silver and wine service. Design flaws seem to have been common; one wonders if an airplane was better crashed, since the costs from the government would be written off and the things wouldn't have to be maintained or operate properly. Meteors had rear cockpit design flaws [p 122], the Canberra cockpit was hard to see out of [p 145 for an account of raising its seat to the highest possible point], bodily relief facilities were a joke, bells and whistles [p 147] were luxuries, and so on. The French, who are off-stage in this book, seem to have handled things more competently, up to a point.

Summarising, this is an unwitting account of simpletons who may turn out to have contributed to the extinction of their entire race. The Second World War is presented in an outdated infantile good vs bad way. Some of the readers of this book must themselves have bombed innocents, including women and children, and led slowly to the present state where the USA and its underling is more hated than any other country. Incidentally Hamilton-Paterson mentions Israel's air equipment without any acknowledgement of frauds and funding. He gives a peep into the world of official secrets and power: the daredevil pilot who 'beat up' London, sacked with no court martial (to sidestep any investigation of his complaints), then 'invalided out' (to prevent examination of his personal case); threatened with loss of pension, and no doubt the Official Secrets Act to prevent publication. Though whether, in view of secrecy generally, he could have made a good case must be doubtful.

I'd have liked something on the effects of computers—on assessing plane design, and in simulators for pilots. He might have mentioned Eisenhower's founding in the 1950s of NASA, the huge ruminant cash cow. He might have alluded to whistleblowers such as Smedley Butler, Rassinier, Veale and many others, including those who could tell a thing or two, but never do. As I finish this typing, I notice the BBC radio programme, exquisitely painful garbage, The Archers, is running, just as it was in the 1950s. Sigh.

Addendum: I found, in David Irving's website fpp.co.uk, a link to a BBC article of 5 June 2014, discussing the 'liberation of France'. Possibly published because Irving's forthcoming volume 3 on Churchill will detail the WW2 bombing of about 1,000 French towns.

'According to research carried out by Andrew Knapp, history professor at the UK's University of Reading, British, American and Canadian air raids resulted in 57,000 French civilian losses in World War Two.

"That's a figure slightly below, but comparable to, the 60,500 the British lost as a result of Luftwaffe bombing over the same period," says Knapp who is the co-author of Forgotten Blitzes and a book just published in France called Les francais sous les bombes alliées 1940-1945 (The French Under Allied Bombardment).

"It is also true that France took seven times the tonnage of [Allied] bombs that the UK took [from Nazi Germany]," says Knapp. "Roughly 75,000 tonnes of bombs were dropped on the UK [including Hitler's V missiles]. In France, it's in the order of 518,000 tonnes," he says.

"France was the third country most bombed by the Allies after Germany and Japan and it is hardly mentioned in our history books."