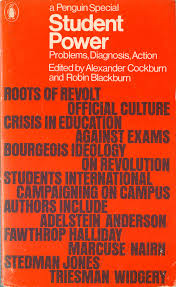

Edited by: Alexander Cockburn & Robin Blackburn: Student Power (1969)

Truths about Jews | Big-Lies Home Page

Agitation against an obscure speech by Enoch Powell gives a perfect example from the time of this book. Jewish policy was and is to force immigrants into Britain at the expense of the locals, and demonstrations in student unions against Powell were made to seem 'spontaneous' and of course had zero intelligent analysis.

This pattern is standard worldwide: a completely different example is the giving of money to 'Evangelical Christians' in the USA, where they spread their rubbish and make Americans look like fools.

The 'foreign intellectuals' listed are of course unidentified Jews. It wasn't their 'quantum of talent' that got them where they were put; it was simply selection for Jewishness. The important question is: who put them there. And what did they actually do. 2024: This was part of the Jewish victory of World War 2.

If you don't understand this, you are, like many millions of people, helplessly ignorant of the world. If this is new to you, please try to grasp its importance.

My notes were made about 1995, when home scanning and optical character recognition were made possible, but weren't efficient.

I put them here 'as is', hoping they might be of some use, not making any special claims.

At the time I was unaware of the constant Jewish activity, over millennia, and was unaware of other secret societies. The notes are as I'd left them. Some parts were scanned in. At the time, universities were funded by grants, and seemed cheap. Lecturers were given contracts to retiring age. There was a lot of scrambling for position. Lecturers were paid more or less by time; they had little incentive to be interesting, or help students, or create anything which might be copied. I had no idea that many positions were offered to Jews, as a secretive unofficial policy.

There's little on the administrative side of universities: 'Students Unions' were generally run by 'Presidents' who may not even belong to the university, and the finances and student papers were run by cliques, union vans were co-opted. Jewish arrangements, e.g. film societies showing Soviet films, public meetings on supposedly contentious issues such as Enoch Powell on immigration, anti-'racialism' societies, were common enough. At the time, a new biological sciences block was being built; looking back, this must have included many fake science techniques.

There was nothing very clear that I recall on Jewish central banking. And of course nothing on Jewish networking. The 'Holocaust' fraud existed, but not very firmly; the nuclear and moon landing frauds were known to nobody in the general student body. The Vietnam War was completely censored in the large-scale media.

However, most students had no idea what was happening, and I presume concentrated on their work.

- My interest in this revived, particularly Robin Blackburn 'A Brief Guide to Bourgeois Ideology', and Perry Anderson 'Components of the National Culture' [on university subjects and their limitations], with Adelstein's 'Roots of the British Crisis', and Linda Tinkham on education colleges, Nairn and Singh-Sandhu on art colleges [structure of education: elitist universities, polys etc below them]. 'The CIA and Student Politics' is good on CIA funding, and in fact virtual creation, of international student organisations, and 'Students of the World Unite' is good on France, Germany, Italy, and Japan.

- Weaknesses: [1] Serious problem is they're all concerned just with over-18 type students; the general population doesn't get much of a look in. Hence as Eve said, the workers are liable to say things like "We don't need you fucking students" or, as I once heard at Reading, "Nothing important ever came out of a University."

[2] They are largely obsessed by Marx, and irritated that ideas like exploitation, capitalism etc are barely mentioned in academic sociology and economics, and for example Hegel isn't taken seriously. But suppose they were? What would change? It's not obvious that, apart from some alterations, anyone has superior insights into society. For instance, military sociology is notorious for barely existing, and, here, it's barely mentioned too; monarchy and church theory should be notorious for not existing, but isn't even that, and here again these don't appear. Again, they think, after Marx, that 'capitalism' is a stage, like 'feudalism' etc; they don't seem to realise credit seems impossible to eliminate, and must have existed in some form in all societies.

Those intellectuals who are included are almost all Marxist [or e.g. Freudians, or people like Talcott Parsons (Joke: described somewhere as of undoubted intellectual distinction!) and Weber and Hegel]; perhaps this explains why they think foreign thinkers became overwhelmingly dominant at some time after say the 1930s.

[Note: knowledge islands: various writers who appear seem to appear grouped together: Frantz Fanon, for example, with a list ...###]

Years after noting this, it struck me that it's no accident that Marxism was tolerated/ encouraged: it is completely useless, with its jargon and emphasis just on one of many power struggles, absence of anything on militarism, absence of science and therefore of importance of raw materials etc, absence of anything on propaganda and education, absence of discussion of splits in working classes.. I imagine it was looked upon with worry at first, but later accepted in Darwinian fashion as its hopeless nothingness became clearer.

Consider by contrast e.g. Wells, with Republicanism, world government, and international expertise united in an 'open conspiracy'; any of these ideas is more useful than Revolution & idea of economic determination of classes

Also occurred to me that the non-Marxian sociology they think so wonderful is itself concerned with unimportant problems: suicide (one of the least important of any phenomena) and bureaucracy (a footnote to modern industrialism) are two examples which occur to me. One of their attacks is 'reification': workers are made into things. It doesn't occur to them that their attitude to raw materials and products of ingenuity is just as much 'reification'; cf e.g. Sarah Potter not thinking much of the production of plastic washing-up bowls

[3] The idea that students could form a major power bloc and go on strike seems far fetched, perhaps wrongly. Adelstein thinks that shortage of trained manpower is a big problem in capitalist societies, so this is their point of leverage. Adelstein accepts the idea of a brain drain; I've heard arguments in New Scientist and elsewhere that this is a myth

[4] None of them knows anything about science. Adelstein says that pupils looking for excitement know from school not to go into science; and that science [paradoxically, unlike theology] is imparted in a leaden, dogmatic way. I came across another author who took exactly the same line to science teaching ['.. no intellectual component' or something], so I assume it's taken for granted. [Linda Tinkham says the opposite about religious instruction in teaching colleges: it's evasive, unhelpful]. There's no mention of the problem that science is largely made up from working-class people.

And none of them seem to know about 'fine art' or about more popular art - films, novels, TV. This all seems to be 'the spectacle'.

Note: rule of 3: 'economic, political and social' influences seems to be a trilogy endlessly repeated.

[5] Tendency to silly jargon, like 'over-determined'. 'Reified' (which I suppose is no odder than 'deified') is misspelt 're-ified' in several places. There's a sprinkling of semi-medical terms contributed by Dave Widgery, later a GP occasionally writing in the Guardian, like 'ataraxy', 'wizened'. Tom Nairn, oddly, doesn't use art criticism terms.

Joke: 'new left' appears as 'la nouvelle gauche' in a French title.

[6] Rather odd tendency of British writers not to criticise their own country's past; for example, several laudatory quotes explain High Victorian attitudes, but there's no mention of British imperialism; the Empire gets just a few mentions. Considering their complaints about 'provincialism' and 'mediocrity' this seems odd. Similarly, the First World War is treated as a given; the possibility of Germans etc bringing things on themselves isn't considered.

[7] Narrow range of influences is considered; Wells, Shaw, Belloc, Chesterton, Russell, Church of England, popular writers, thrillers and best sellers, music, art, architecture, town planning, council housing, James Jeans, radio, radar, the Blitz, Zionism, the rise of the Labour Party, the depression, dropping the gold standard, pressure for tariffs, the cinema, TV, T S Eliot, changes in farming, surrealism, Swiss banks, air warfare are just some of the things omitted from their school education and hence, apparently, from their written work.

CONTENTS:

INTRODUCTION Alexander Cockburn

THE MEANING OF THE STUDENT REVOLT Gareth Stedman Jones

ROOTS OF THE BRITISH CRISIS David Adelstein

LEARNING ONE'S LESSON Linda Tinkham

EDUCATION OR EXAMINATION? Tom Fawthrop

CHAOS IN THE ART COLLEGES Tom Nairn & Jim Singh-Sandhu

NUS - THE STUDENT'S MUFFLER David Widgery

THE CIA AND STUDENT POLITICS David Triesman

A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY Robin Blackburn }} Parts scanned in

The Jewish rabbinical view, embodied in the Kahal system, is that what's theirs is mine, and what's yours will be mine, after the Kahal has done its work.

A 'bourgeois' is a person or group who is non-Jewish and owns money or assets. The ownership is viewed by Jews as shocking and temporary and up for spoliation.

When Jews in the USA talk about 'flyover States', or Blackburn discusses non-Jewish teachers or politicians, or the Jewish 'historian' Simon Schama sneers at Suburbia, this is their hidden meaning. - RW 2023

COMPONENTS OF THE NATIONAL CULTURE Perry Anderson }} Fri 11 August 95

STUDENTS OF THE WORLD UNITE Fred Halliday

CAMPAIGNING ON THE CAMPUS Carl Davidson

ON REVOLUTION Herbert Marcuse

WHY SOCIOLOGISTS? Nanterre Students

- NB: FUTURE CAREERS: DAVE WIDGERY, then 20, died 'tragically' [I don't know what from] in October 1992. The BBC showed on 6 April 1993 a sort of vague biographical programme, describing him as a 'committed socialist', which seemed exclusively concerned with his life as a GP in London, E14, which he liked. Shots of women at phones waiting for ambulance service to return calls, old man who'd been a steel erector and in Antarctica waiting for a wheelchair, families in many cases black receiving houses - surely not much to do with GPing - discussion of smears for women etc. At the time he was about to take a year off to research 19th century medical conditions in London: ".. In the 19th century... chaotic condition.. private enterprise.. GPs competing with each other.. hospitals under siege.. a ghastly mirror.. the great achievement of the NHS was to make doctors one block, stopped GPs competing with each other.." He was black-leather-jacketed, somewhat resembled people like Laing in being not incredibly well spoken, was nearly bald and looked older than his years. He seemed quite cheerful. He blandly accepted modern technology - phone exchanges, faxes, cars, small computers. [He contributed to the Guardian; my notes mention at least one of his articles].

TOM NAIRN: I have notes on some of Nairn's later books elsewhere.

DAVID ADELSTEIN in about 1975 was a lecturer in sociology at some London place, then I think a poly; I remember Elaine Unterhalter getting on well with him, visiting the Playboy Club with him as a joke. He didn't impress Matthew's ex-commie woman friend, who said he lay on a sofa and wouldn't talk to anyone at a guy fawkes night party or something.

DAVID TRIESMAN ('The CIA and student Politics') in Sept 94 Red Pepper is General Secretary of the Association of University Teachers (saying they're afraid to speak out on issues of competence & funding..)

- 55: [Gramsci on organic and traditional intellectuals, exactly as in Edward Said's 1993 Reith Lectures]

- 163ff: [THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE. FIRST OF TWO IS: Robin Blackburn: A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY:]

'The first concern of a revolutionary student movement will be direct confrontation with authority, whether in the colleges or on the barricades. But the preparation and development of such a movement has always entailed a searching critique of the dominant ideas about politics and society - in this way practice and theory reinforce one another. These dominant ideas are invariably produced, or reproduced, within the university itself. For many students, to contest these ideas is to question what they are taught. It is therefore not surprising that social science faculties are usually so heavily involved in student revolt. Some of the most articulate champions of academic reaction are professors of sociology, industrial relations or some allied subject. At the same time the social science faculties always provide a prominent contingent in student revolts. In Britain, as elsewhere, the student who takes up sociology, economics or political science finds he or she has to reject the conformist ideas and technocratic skills which his teachers seek to instil.

My intention here is to try to identify the prevailing ideology in the field of the social sciences as taught in British universities and colleges. This ideology, I hope to show, consistently defends the existing social arrangements of the capitalist world. It endeavours to suppress the idea that any preferable alternative does, or could exist. Critical concepts are either excluded (e.g. 'exploitation', 'contradiction') or emasculated (e.g. 'alienation', 'class') It is systematically pessimistic about the possibilities of attacking repression and inequality: on this basis it constructs theories of the family, of bureaucracy, of social revolution, of 'pluralist' democracy all of which imply that existing social institutions cannot be transcended. Concepts are fashioned which encapsulate this determinism (e.g. 'industrial society') and which imply that all attempts to challenge the status quo are [164 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE] fundamentally irrational (e.g. 'charisma').

The Assumptions of Capitalist Economics

Let us begin where the capitalist system itself begins, with the exploitation of man by man. We shall see that capitalist economics refuses to consider even the possibility that exploitation lies at the root of inequality or poverty- one can acquire

1. Joan Robinson, Economic Philosophy, UK, 1962, p. 28.

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 165]

a first class degree in economics in Britain without ever having studied the causes of these phenomena. It is now a well established (though not so well known) fact that economic inequality within most capitalist countries has remained roughly constant for many decades. In Britain, for example, the share of national income going to wages and the share going as profits has remained more or less the same since the statistics were first collected towards the end of the nineteenth century: the richest 2 per cent of British adults own 75 per cent of all private wealth, while the income of the top one per cent of incomes is in sum about the same as that shared out among the poorest third of the population. Marx and the classical economists tried to explore the causes of such phenomena in sharp distinction to their neglect by most modern bourgeois economics. The shift in emphasis is stated as follows by a recent historian of the subject:

Marx inherited both the strengths and the weaknesses of his classical forerunners. In both theoretical systems, the central analytical categories were moulded to illuminate the causes and consequences of long term economic change and the relationship between economic growth and income distribution. The tools useful for these purposes were not, however, well adapted (nor were they intended to be) to a systematic inspection of other matters: e.g. the process through which market prices are formed and the implications of short term economic fluctuations.2

It is these latter questions which have for so long preoccupied the main bourgeois economists and all too often the conceptual tools developed in these inquiries are then used to tackle the larger issues with predictable lack of success. Thus in the age of attempted 'incomes policies' economic theory is quite incapable of accounting for the share of national income represented by profits. In the most recent edition of a now standard text book we read:

We conclude by raising the interesting question of the share of profits in the national income. We have no satisfactory theory of the share of national income going as profits and we can do little to

2.W.J.Barber, A History of Economic Thought, Penguin, UK, 1967, p.161

[166 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE]

explain past behaviour of this share, nor do we have a body of predictions about the effect on this share of occurrences like the rise of unions, wage freezes, profits taxes, price controls etc.3

In his conclusion on theories of income distribution as a whole Professor Lipsey confesses: 'We must, at the moment, admit defeat; we must admit that we cannot at all deal with this important class of problems.' His solution to the impasse is a little lame, faced with all this: 'There is a great deal of basic research that needs to be done by students of this subject.'

A re-examination of the tradition of Marx and the classical economists would have given these researchers the analytical categories they so evidently need. In fact the most promising work in this field is being done on precisely this basis but without acknowledgement from the mainstream of bourgeois economics.4 For Marx, the tendency of capitalism to generate wealth at one pole and poverty at the other, whether on the national or international scale was a consequence of the exploitive social relations on which it was based. For bourgeois social science, the very concept of 'exploitation' is anathema since it questions the assumed underlying harmony of interests within a capitalist society. But of course the rejection of this concept is carried out in the name of the advance of science not the defence of the status quo. For example, the whole question is disposed of in the following fashion by Samuelson in the other main economics text book: 'Marx particularly stressed the labor theory of value that labor produces all value and if not exploited would get it all.... Careful critics of all political complexions generally think this is a sterile analysis . . .' 5 The tone of this remark is characteristic with its reference to the academic consensus which the student is invited to join. A more recent work on this subject makes greater concessions to the 'sterile analysis' but preserves the essential taboo on the key concept: the author writes that we must 'retain the germ of truth in Marx's observation of the wage bargain as one of class bargaining or conflict without the loaded formula-

3. R G Lipsey, An Introduction to Positive Economics, UK, 1967, p. 481.

4. The work of Piero Sraffa and his school.

5. P.A Samuelson, Economics, Fifth Edition, USA, 1961, pp. 855-6. Samuelson's account of Marx's theory contains numerous factual errors: he attacks Marx's Iron Law of Wages, a concept of Lassalle's

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 167]

tion of the concept "exploitation".'

6 By excluding a priori such ways of analysing economic relationships, modern bourgeois economics ensures that discussion will never be able to question the capitalist property system. Thus Lipsey writes:

Various reasons for nationalizing industries have been put forward and we can only give very brief mention to these. 1. to confiscate for the general public's welfare instead of the capitalist's. In so far as nationalized industries are profitable ones and in so far as they are not any less efficient under nationalization than in private hands this is a rational object. Quantitively [sic] however it is insignificant besides such redistributive devices as the progressive income tax.7

Lipsey is to be congratulated for sparing a few lines to such thoughts in his eight hundred page tome - most bourgeois economists simply ignore the idea altogether. However, his argument is patently ideological. Firstly, his confidence in the redistributive effects of taxation is in striking contrast to his statements made a few pages earlier, and quoted above, that he cannot with current theory say anything useful about income distribution or the effects on it of taxation. More important is the implicit assumption that capitalists' profits are being confiscated but they are being compensated for the take-over of their property. Nationalization without compensation would have an immediate, massive and undeniable effect on distribution. Even when the bourgeois economist steels himself to consider the prospect of socialism being installed in an advanced capitalist country, he usually finds it impossible to imagine the complete elimination of property rights. In Professor J. E. Meade's Equality, Efficiency and the Ownership of Property, he constructs a model where we find that the fledgling 'Socialist State' is burdened from the outset with a huge national debt. It seems that the mind of the bourgeois social scientist is quite impervious to any idea that 'property is theft' or that the expropriators

which Marx emphatically rejected; we are told that according to Marx the worker should receive in wages the full fruits of his labour, again a view which Marx explicitly rejected. cf. Karl Marx, A Critique of the Gotha Program.

6. Murray Wolfson, A Reappraisal of Marxian Economics, USA, 1966, p. 117.

7. R. G. Lipsey, An Introduction to Positive Economics, p. 532.

[168 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE]

should be expropriated. Instead the only 'rational' objectives for him are ones defined by the rationality of the system itself. A good example of this is provided by Samuelson's discussion of the problems raised by redundancy in a capitalist economy.

Every individual naturally tends to look only at the immediate economic effects upon himself of an economic event. A worker thrown out of employment in the buggy industry cannot be expected to reflect that new jobs may have been created in the automobile industry ! but we must be prepared to do so.8

The 'we' here is all aspirant or practising economists. Nobody, it seems will be encouraged to reflect that workers should not individually bear the social costs of technological advance, that their standard of living should be maintained until alternative employment is made available to them where they live etc. For the bourgeois economist the necessities of the social system are unquestionable technological requirements. The passage quoted dedicated to informing the student that: 'the economist is interested in the workings of the economy as a whole rather than in the viewpoint of any one group.' 9

To make his point clear he adds:

... an elementary course in economics does not pretend to teach one how to run a business or a bank, how to spend more wisely, or how to get rich quick from the stock market But it is to be hoped that general economics will provide a useful background for many such activities.lø

The one activity to which this brand of economics certainly does not provide a useful background is that of critical reflection on the economy 'as a whole' and the social contradictions on which it is based.

Classical economics could analyse class relationships because it was a constitutive part of 'political economy', the study of social relations in all their aspects. In contemporary social science the economic, political and sociological dimensions of

8. P A. Samuelson, op. cit, p. 10 The complex nature of capitalist rationality is admirably discussed in Maurice Godelier's Rationalite et Irrationalite en Economie, Paris, 1967.

9. P. A. Samuelson, ibid., p. 10.

10. P. A. Samuelson, ibid., p. 10.

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 169]

society are split up and parcelled out among the different academic departments devoted to them. This process itself helps to discourage consideration of the nature of the economic system on other than its own terms. The whole design is lost in the absorption with details. It also allows inconsistencies to flourish within the ideology without causing too much intellectual embarrassment. For example, most economists studying the theory of the firm assume that the goal of businessmen is to maximize profits. Sociologists, on the other hand, assume that since the 'managerial revolution', business decisions are not designed to maximize even long-term profits but are rather prompted by more positive-sounding considerations - public welfare, economic growth, etc. This apparent clash of assumptions reflects only the division of labour between the two disciplines. Economics, the more 'practical' of the two, has to remain closer to the way things actually work in a capitalist economy while sociology provides a justificatory theory which does not interrupt 'business as usual' in the real world. In its turn the economic assumption of profit maximization is validated by the theory that business decisions only reflect the needs ('utility curve' or 'indifference curve') of the sovereign consumer. The naivete of the utility theory is offensive to sociologists but then it is not necessary to them since they have opted for the (equally na‹ve) managerial revolution thesis. However, on certain key concepts the same taboos operate in sociology that we have seen in economics. For example,

In the now nearly forgotten language of political economy, 'exploitation' refers to a relationship in which unearned income results from certain types of unequal exchange.... Doubtless 'exploitation' is by now so heavily charged with misleading ideological resonance that the term itself can scarcely be salvaged for purely scientific purposes and will, quite properly, be resisted by most American sociologists Perhaps a less emotionally freighted - if infelicitous - term such as 'reciprocity imbalance' will suffice to direct attention once again to the crucial question of unequal exchanges.11

11. Alvin Gouldner, 'The Norm of Reciprocity', in Social Psychology, Edward E. Sampson (ed) USA, 1964, pp. 83-4. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly those who have followed Gouldner's advice have only succeeded in emasculating the idea in question. cf. Peter Blau, Exchange

[170 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE]

Gouldner goes on to point out that though this concept has been taboo in macro-social analysis of relations between social groups, this is not the case for micro-social analysis. In studying sexual relations or the doctor-patient relationship the term 'exploitation' does occur in the writings of even the most respectable sociologists. An English social philosopher who finds Marx's usage objectionable proposes that we should consider the ways in which the weak exploit the strong: 'In some circumstances, as the cases of the beggar and of Dr Moussadek (of Persia) show, weakness can be a favourable position from which exploitation may be exercised.'12 Sociology's separation from economics, and its rejection of most political economy, produces some curious results. Thus, for example, poverty, an important feature of all advanced capitalist countries, becomes a phenomenon which is dissociated from the way the economic system operates. Instead it is a socially defined 'problem' which can be solved by getting the poor to change their values:

The thesis of this chapter is that disreputable poverty, and not poverty in general, presents a serious social problem to society and a profound challenge to its capacities and ingenuity. ... The disreputable poor may be considered - indeed they may be defined - as that limited section of the poor whose moral and social condition is relatively impervious to economic growth and progress.13

_____

and Power in Social Life, USA, 1964. The vacuum created by an absent political economy has allowed a new genre to flourish which seems to be a journalistic amalgam of pop sociology and half-baked economics: see, for example, Andrew Schonfield, Modern Capitalism, UK, 1965, or J. K. Galbraith, The New Industrial State, UK, 1968.

12. H. B. Acton, The Illusion of the Epoch, UK, 1957, p. 243.

13. David Matza, 'Poverty and Disrepute', Contemporary Social Problems, Robert K. Merton and Robert A. Nisbet, USA, 1965, p. 619. Of course capitalism creates not only poverty but also a characteristic 'culture of poverty'. Writers like Matza do not see any link between the cultural dimensions of poverty (for example, the poor's resignation and fatalism) and the nature of the social system. Oscar Lewis has provided a most powerful evocation and analysis of the culture of poverty in Children of Sanchez, La Vida and other writings. In the introduction to La Vida he contrasts Puerto Rico with revolutionary Cuba, suggesting that the latter country, though still poor, has overcome the fatalism associated with the culture of poverty in capitalist societies.

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 171]

Imperialism and Social Science

The ideological character of a sociology which assumes on principle a harmonious economic system is particularly evident when the relations between advanced and backward countries are being examined. It is now widely acknowledged that the gap between them is growing and it should be equally evident that the relations between them involve the domination and exploitation of poor capitalist nations by rich ones. Between 1950 and I965 the total flow of capital on investment account to the underdeveloped countries was $9 billion while $25 6 billion profit capital flowed out of them, giving a net inflow from the poor to the rich in this instance of $16.6 billion.'14 Yet we are informed by Professor Aron that 'In the age of the industrial society there is no contradiction between the interests of the underdeveloped countries and those of advanced countries.'15 Talcott Parsons is also determined to ignore what he calls 'irrational accusations of imperialism'. He writes,

My first policy recommendation, therefore, is that every effort be made to promulgate carefully considered statements of value commitments which may provide a basis for consensus among both have and have-not nations. This would require that such statements be disassociated from the specific ideological position of either of the polarized camps.16

Parsons's notorious obsession with values is patently ideological in such a context - especially since he goes on to assert that in creating this consensus atmosphere 'the proper application of social science should prove useful'. Nowhere in this essay on the 'world social order' does Parsons discuss the role of the capitalist world market or the US Marine Corps as forces acting to maintain the status quo. Further, note the sheer fatuousness of

14. Harry Magdoff, 'Economic Aspects of U.S. Imperialism', Monthly Review, November 1966, p. 39. Of course, there are other aspects of imperialism than this. See, for example, May Day Manifesto 1968, edited by Raymond Williams, Penguin Books, pp. 66-85, and Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment, USA, 1966.

15. Raymond Aron, The Industrial Society, UK, 1967, p. 24.

16. Talcott Parsons, Sociological Theory and Modern Society, UK, 1968, p. 475.

[172 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE]

Parsons's belief that anything would be changed by the promulgation of carefully considered statements, etc. Even Parsons's undoubted intellectual distinction is no protection against the feebleness imposed on its devotees by bourgeois ideology.

The radically distorted perspective encouraged by the Parsonian emphasis on the autonomous efficacy of values shows up very clearly in such studies as Elites in Latin America edited by Seymour Lipset and Aldo Solari. In a book supposedly devoted to elites there is no contribution on landowners who have traditionally been such an important element in the Latin American oligarchy. On the other hand there are seven contributions on aspects of the educational system including such topics as 'Education and Development', 'Opinions of Secondary School Teachers' and 'Relations between Public and Private Universities'. The general argument emerging from such works is that development of the underdeveloped regions will ensue if schoolteachers can be persuaded to instil healthy capitalist values in their pupils. The whole programme is offered as an alternative to social revolution:

Although revolution may be the most dramatic and certainly the most drastic method to change values and institutions which appear to be inhibiting modernization, the available evidence would suggest that reforms in the educational system which can be initiated with a minimum of political resistance may have some positive consequences.17

Another striking instance of the excessive value emphasis encouraged by Parsonian theory is The Politics of Developing Areas by G. Almond and J. S. Coleman. This book, published in 1960, so persistently ignored Mao's dictum that 'power grows out of the barrel of a gun' that the index contains no reference for 'army', 'armed forces', etc, and its discussions have been completely bypassed by the subsequent wave of military coups throughout the underdeveloped zone. The assumption usually made in such writings is that the 'West' provides the model for the development of the underdeveloped world. The fact that the Western capitalist powers were plundering the rest of the world

17. S. M. Lipset, 'Values, Education and Entrepreneurship', in Elites in Latin America, ed. S. Lipset and A. Solari, USA, 1967, p. 41.

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 173]

at the time of their industrialization, whereas the underdeveloped world is in the reverse position, is rarely considered. The profits of the slave trade, the sales of opium to China, the plantations of the Americas etc. (not to speak of the expropriation of the common lands of the European peasantry and the grazing grounds of the American Indian) all contributed to the early capital accumulation of the Western Imperialist powers quite as much as their devotion to a 'universalistic' value system. Curiously enough, bourgeois economists do not recommend underdeveloped countries to follow the Western model in this respect. In all the mountains of literature devoted to the strategy of economic development, writers who urge the poor countries to nationalize the investments of the rich are very rare. Martin Bronfenbrenner's excellent article on 'The Appeal of Confiscation in Economic Development', first published in 1955, has evoked almost no response and most textbooks on development strategy ignore the question altogether.

Not surprisingly the best allies of foreign capital in the underdeveloped regions are the remaining traditional elites and the feeble local capitalist class. At one time it was hoped by Western strategists that the 'middle sectors' could carry through the process of economic development in their respective countries. This ignored the fact that the context provided by the imperialist world market invariably poses an insuperable obstacle to the underdeveloped bourgeoisie of the poor capitalist countries. As a consequence they have usually sought enrichment through battening on a corrupt government or sponsoring a military coup rather than producing the hoped-for economic advance.18 All this creates most unpleasant dilemmas for the bourgeois social scientist and accounts for the growing acceptance of development strategies based on an analysis such as the following :

I am trying to show how a society can begin to move forward as it is, in spite of what it is. Such an enterprise will involve a systematic search along two closely related lines: first, how acknowledged, well entrenched obstacles to change can be neutralized, outflanked and left to be dealt with decisively at some later stage; secondly

18. The writings of Frantz Fanon, Regis Debray, Andre Gunder Frank and Jose Nun, explore different aspects of this process.

[174 THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE]

and perhaps more fundamentally, how many among the conditions and attitudes that are widely considered as inimical to change have a hidden positive dimension and can therefore unexpectedly come to serve and nurture progress.19

This fantasy enables the bourgeois social scientist to ignore the fact that the main obstacles to development are either directly provided by imperialist domination or buttressed by it.

The attraction of the Hirschman approach is increased as earlier illusions about 'underdevelopment' are eroded. The economists, in particular, have often acted as if economic development can be induced as soon as a few well-meaning tax reforms are enforced. The fiasco of Nicolas Kaldor's policies in India, Ceylon, Ghana, Guyana, Mexico and Turkey illustrate this well:

Since I invariably urged the adoption of reforms which put more of the burden of taxation on the privileged minority of the well-to-do, and not only on the broad masses of the population, it earned me (and the governments I advised) a lot of unpopularity, without, I fear, always succeeding in making the property-owning classes contribute substantial amounts to the public purse. The main reason for this ... undoubtedly lay in the fact that the power, behind the scenes, of the wealthy property-owning classes and business interests proved to be very much greater than ... suspected.20

On the whole, bourgeois economists only achieve such revelations in connexion with remote places whose local 'privileged minority' appear to impede imperialist penetration. Even then they usually persist in believing that their technical nostrums can be made to work:

In most underdeveloped countries, where extreme poverty coexists with great inequality in wealth and consumption, progressive taxation is, in the end, the only alternative to complete expropriation through violent revolution.... The progressive leaders of underdeveloped countries may seem ineffective if judged by immediate results; but they are the only alternatives to Lenin and Mao Tse Tung.21

19. Albert O. Hirschman, Journeys Towards Progress, USA, 1963, pp. 6-7.

20. Nicolas Kaldor, Essays on Economic Policy, UK, I964, Vol. I, pp. xvii-xx.

21. ibid.

[A BRIEF GUIDE TO BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY 175]

The political exclusion of expropriation could scarcely be more unabashed.

The rejection of 'entrepreneural' values by the more militant representatives of the Third World is a problem for Western sociologists like Parsons. He attempts to explain it in terms of 'the inferior status of the rising elements':

Here, precisely because the core elements of the free world have already at least partially achieved the goals to which the developing nations aspire, there is a strong motivation to derogate these achievements. In ideological terms the aim of these nations is not to achieve parity but to supplant certain well-established elements of the 'superior' society, for example, to substitute socialism for capitalism. ... The direction of desirable change seems clear; ideological stresses must be minimized; those aspects of the situation which demonstrate an interest in order which transcends polarity must be underscored. One of the main themes here concerns those features which all industrial societies share in common.... An exposition of such features would necessarily focus on the standard of living of the masses - for obvious reasons a very sensitive area for the communists. ... This discussion has been based on ... the assumption that one side has achieved a position of relative superiority in relation to the important values.22

Parsons goes on to say that the reconciliation of the inferior elements and the core elements of the free world on the basis of the latter's superior values can be achieved partly by drawing on a 'very important resource, namely the contribution of social science'. This explicitly ideological orientation towards underdevelopment has already introduced us to a major theme of bourgeois ideology in the context of advanced countries - namely the category 'industrial society'. The time has come to consider its implications.

'Industrial Society' and Technological Determinism

The category 'industrial society' has now become the accepted definitional concept for modern capitalism. Raymond Aron, who has done much to promote it, makes clear its intention: it is, he writes, 'a way of avoiding at the outset the opposition between

22.Talcott Parsons, Sociological Theory and Modern Society, pp. 485-6.

...'

- 226ff: [THE REPRESSIVE CULTURE. SECOND OF TWO IS:

Most of this extracted from Perry Anderson, Components of the National Culture, from Student Power, Edited by A Cockburn & R Blackburn, a 1969 Penguin paperback.

v. 6 May 2016 11:51

'.. sui generis creed of this class produced by its intellectuals, utilitarianism, was a crippled caricature of such an ideology, with no chance whatever of becoming the official justification of the Victorian social system. The hegemonic ideology of this society was a much more aristocratic combination of 'traditionalism' and 'empiricism', intensely hierarchical in its emphasis, which accurately reiterated the history of the dominant agrarian class. The British bourgeoisie by and large assented to this archaic legitimation of the status quo, and sedulously mimicked it. After its own amalgamation with the aristocracy in the later nineteenth century, it became second nature to the collective propertied class.10

What was the net result of this history? The British bourgeoisie from the outset renounced its intellectual birthright. It refused ever to put society as a whole in question. A deep, instinctive aversion to the very category of the totality marks its entire trajectory.11 It never had to recast society as a whole, in a concrete historical practice. It consequently never had to rethink society as a whole, in abstract theoretical reflection. Empirical, piecemeal intellectual disciplines corresponded to humble, circumscribed social action. Nature could be approached with audacity and speculation: society was treated as if it were an immutable second nature. The category of the totality was renounced by the British bourgeoisie in its acceptance of a comfortable, but secondary station within the hierarchy of early Victorian capitalism.'2 In this first moment of its history, it did not need it. Because the economic order of agrarian England was already capitalist and the feudal State had been dismantled in the seventeenth century, there was no vital, indefeasible necessity for it to overthrow the previous ruling class. A common mode of production united both, and made their eventual fusion possible. The cultural limitations of bourgeois reason in England were thus politically rational: the ultima ratio of the economy founded both.

Superfluous when the bourgeoisie was fighting for integration into the ruling order, the notion of the totality became perilous when it achieved it. Forgotten one moment, it was repressed the next. For once the new hegemonic class had coalesced, it was naturally and resolutely hostile to any form of thought that took the whole social system as its object, and hence necessarily put it in question. Henceforward, its culture was systematically organized against any such potential subversion. There were social critics of Victorian capitalism, of course: the distinguished line of thinkers studied by Williams in Culture and Society. But this was a literary tradition incapable of generating a conceptual system. The intellectual universe of Weber, Durkheim or Pareto was foreign to the pattern of British culture which had congealed over the century. One decisive reason for this was, of course, that the political threat which had so largely influenced the birth of sociology on the continent - the rise of socialism did not materialize in England. The British working class failed to create its own political party throughout the nineteenth century. When it eventually did so, it was twenty years behind its continental opposites, and was still quite untouched by Marxism. The dominant class in Britain was thus never forced to produce a counter-totalizing thought by the danger of revolutionary socialism. Both the global ambitions, and the secret pessimism, of Weber or Pareto were alien to it. Its peculiar, indurated parochialism was proof against any foreign influences or importations. The curious episode of a belated English 'Hegelianism', in the work of Green, Bosanquet and Bradley, provides piquant evidence of this. Hegel's successors in Germany had rapidly used his philosophical categories to dispatch theology. They had then plunged into the development of the explosive political and economic implications of his thought. The end of this road was, of course, Marx himself. Sixty years after Bruno Baeur [sic] and Ludwig Feuerbach, however, Green and Bradley innocently adopted an aqueous Hegel, in their quest for philosophical assistance to shore up the traditional Christian piety of the Victorian middle class, now threatened by the growth of the natural sciences.l3 This anachronism was naturally short-lived. It merely indicated the retarded preoccupations of its milieu: a recurring phenomenon. Two decades earlier, George Eliot had solved her spiritual doubts by borrowing Comte's 'religion of humanity' - not his social mathematics. These importations were ephemeral, because the problems they were designed to solve were artificial. They simply acted as a soothing emulsion in the transition towards a secular bourgeois culture.

228

In a panorama emptied of profound intellectual upheaval or incendiary social conflict, British culture tranquilly cultivated its own private concerns at the end of the long epoch of Victorian imperialism. In 1900, the harmony between the hegemonic class and its intellectuals was virtually complete. Noel Annan has drawn the unforgettable portrait of the British intellectuals of this time. 'Here is an aristocracy, secure, established and, like the rest of the English society, accustomed to responsible and judicious utterance and sceptical of iconoclastic speculation.' 14 [NB: cp Wells on the disruptions of this same period.] There was no separate intelligentsia.15 An intricate web of kinship linked the traditional lineages which produced scholars and thinkers to each other and to their common social group. The same names occur again and again: Macaulay, Trevelyan, Arnold, Vaughan, Strachey, Darwin, Huxley, Stephens, Wedgwood, Hodgkin and others. Intellectuals were related by family to their class, not by profession to their estate. 'The influence of these families,' Annan comments after tracing out their criss-crossing patterns, 'may partly explain a paradox which has puzzled European and American observers of English life: the paradox of an intelligentsia which appears to conform rather than rebel against the rest of society.'16 Many of the intellectuals he discusses were based on Cambridge, then dominated [sic] by the grey and ponderous figure of Henry Sidgwick (brother-in-law, needless to say, of Prime Minister Balfour). The ideological climate of this world has been vividly recalled by a latter-day admirer. Harrod's biography of Keynes opens with this memorable evocation:

If Cambridge combined a deep-rooted traditionalism with a lively progressiveness, so too did England. She was in the strongly upward trend of her material development; her overseas trade and investment were still expanding; the great pioneers of social reform were already making headway in educating public opinion. On the basis of her hardly won, but now solidly established, prosperity, the position of the British Empire seemed unshakeable. Reforms would be within a framework of stable and unquestioned social values. There was ample elbow-room for experiment without danger that the main fabric of our economic well-being would be destroyed. It is true that only a minority enjoyed the full fruits of this well-being; but the consciences of the leaders of thought were not unmindful of the hardships of the poor. There was great confidence that, in due course, by careful management, their condition would be improved out of recognition. The stream of progress would not cease to flow. While the reformers were most earnestly bent on their purposes, they held that there were certain strict rules and conventions which must not be violated; secure and stable though the position seemed, there was a strong sense that danger beset any changes.11

[Anderson's essay begins with a long passage on the Victorian British intelligentsia and politicians, dominated, he thinks, by a small number of families, whose 'names occur again and again', supposedly in a tranquil 'provincial' country—Macaulay, Trevelyan, Arnold, Vaughan, Strachey, Darwin, Huxley, Stephens, Wedgwood, Hodgkin, Sidgwick, and others—'a panorama emptied of profound intellectual upheaval or incendiary social conflict'. Anderson lists 'intellectuals', all, or virtually all, Jews, though of course the word 'Jew' is never mentioned. The influence of Jews on Britain's finances and war effort isn't mentioned either—part of the motive force behind the empire, wars, the US civil war, is completely missing; he doesn't mention the Jewish 'Bank of England' after Cromwell, or the influence of the King James translation of the Bible, a hugely expensive piece of propaganda. Anderson has no discussion of the Jewish coup which devastated Russia following the Federal Reserve coup in the USA. Science frauds, such as nuclear and biological and space issues, which became ever-greater, of course aren't mentioned. Nor are trade unions and 'Communist' (Jewish) influences.

There's a much-promoted idea that the 1960s were influenced heavily by the Vietnam War. However, the issue was used mainly by Jews in their own perceived interests: there's nothing in this book on war profiteers in the USA, war crimes and international law, paper money and Jews and inflation, the use of US troops to make money for Jews. The two editors must be counted as 'useful idiots', front men paid and published by Jews.

The lists Anderson presents are of interest as a parallel to the names of influential Jews in the USA over the same period, discussed for example by Kevin MacDonald. Anderson thinks they are 'white'—not meaning white Russian, but Jews anxious to move from continental Europe. Many names are omitted—a few examples at random of these are A J Ayer, Jonathan Miller, Rosenthal (an opera writer), John Berger (art critic), Nikolaus Pevsner (architecture historian). Anderson does not examine financial motives of academics; there's a British attitude (see for example Galsworthy) that most professors and writers were not well rewarded.]

The ideological climate of this world has been vividly recalled by a latter-day admirer. Harrod's biography of Keynes opens with this memorable evocation:

If Cambridge combined a deep-rooted traditionalism with a lively progressiveness, so too did England. She was in the strongly upward trend of her material development; her overseas trade and investment were still expanding; the great pioneers of social reform were already making headway in educating public opinion. On the basis of her hardly won, but now solidly established, prosperity, the position of the British Empire seemed unshakeable. Reforms would be within a framework of stable and unquestioned social values. There was ample elbow-room for experiment without danger that the main fabric of our economic well-being would be destroyed. It is true that only a minority enjoyed the full fruits of this well-being; but the consciences of the leaders of thought were not unmindful of the hardships of the poor. There was great confidence that, in due course, by careful management, their condition would be improved out of recognition. The stream of progress would not cease to flow. While the reformers were most earnestly bent on their purposes, they held that there were certain strict rules and conventions which must not be violated; secure and stable though the position seemed, there was a strong sense that danger beset any changes.

... Such was the solid, normal world of the English intelligentsia before 1914.

The White Emigration

Occupation, civil war and revolution [sic; what about war?] were the continuous experience of continental Europe for the next three decades. Hammered down from without or blown from within, ... not a single major social and political structure survived intact. Only two countries on the whole land-mass were left untouched, the small states of Sweden and Switzerland. Elsewhere, violent change swept every society in Europe ... , from [Note: odd geography?:] Oporto [near N end of Portuguese coast] to Kazan [capital Tartar republic, Russia; east of Moscow] and Turku [SW Finland] to Noto [small place in SE Sicily]. The disintegration of the Romanov, Hohenzollern and Habsburg Empires, the rise of Fascism, the Second World War, and victory of Communism in Eastern Europe followed each other uninterruptedly. There was revolution in Russia, counter-revolution in Germany, Austria and Italy, occupation in France and civil war in Spain. ... The smaller countries underwent parallel upheavals. [NB: absence of comparison pre-war; e.g. what about Franco-Prussian War? Italian unification?]

England, meanwhile, suffered neither invasion nor revolution. No fundamental institutional change supervened from the turn of the century to the era of the Cold War. Geographical isolation and historical petrification appeared to render English society immutable. Despite two wars, its stability and security were never seriously ruffled. This history is so natural to most Englishmen, that they never registered how praeternatural it has seemed abroad. [2007 note: Belloc made a similar comment, p 224, referring to 'Jews' in 19th century; NB the same surely is true of the USA - it's not therefore as recent as this author thinks.] The cultural consequences have never been systematically considered. But this is the context which has vitally determined the evolution of much of English thought since the Great War.

If one surveys the landscape of British culture at mid-century, what is the most prominent change that had taken place since 1900? It is so obvious, in effect, that virtually no one has noticed it. The phalanx of national intellectuals ... has been eclipsed. ... foreigners suddenly become omnipresent. The crucial, formative influences in the arc of culture with which we are concerned here are again and again emigres. Their quality and originality vary greatly, but their collective role is indisputable. The following list of maîtres d'ecole gives some idea of the extent of the phenomenon:

Ludwig Wittgenstein Philosophy Austria

Bronislaw Malinowski Anthropology Poland

Lewis Namier History Poland

Karl Popper Social Theory Austria

Isaiah Berlin Political Theory Russia

Ernst Gombrich Aesthetics Austria

Hans-Jurgen Eysenck Psychology Germany

Melanie Klein Psychoanalysis Austria

(Isaac Deutscher Marxism Poland)

... The two major disciplines excluded here are economics and literary criticism.

Keynes, of course, completely commanded the former; Leavis the latter. [Both these people could in fact have been Jews - RW] 11 oct 2020 But literary criticism - for evident reasons - has been the only sector unaffected by the phenomenon. For at the succeeding [i.e. post-1945 ish] level, the presence of expatriates is marked in economics ... too: perhaps the most influential theorist in England today is Nicolas Kaldor (Hungary), ... and undoubtedly the most original Piero Sraffa (Italy). There is no need [sic; why not?] to recall the number of other expatriates ... elsewhere - Gellner, Elton, Balogh, Von Hayek, Plamenatz, Lichtheim, Steiner, Wind, Wittkower and others.

The contrast with the 'intellectual aristocracy' of 1900 is overwhelming. But what is its meaning? ... What is the sociological nature of this emigration? Britain is not traditionally an immigrants' country, like the USA. Nor was it ever host, in the nineteenth century, to European intellectuals rising to occupy eminent positions in its culture. ..." Refugees were firmly suppressed below the threshold of national intellectual life. The fate of Marx is eloquent. The very different reception of these expat [231] riates in the twentieth century was a consequence of the nature of the emigration itself - and of the condition of the national intelligentsia.

The wave of emigrants who came to England in this century were by and large fleeing the permanent instability of their own societies - that is, their proneness to violent, fundamental change. 18 England epitomized the opposite of all this: tradition, continuity and orderly empire. Its culture was consonant with its special history. A process of natural selection occurred, in which those intellectuals with an elective affinity to English modes of thought and political outlook gravitated here. Those refugees who did not, went elsewhere. ... It is noticeable that there were many Austrians among those who chose Britain. It is perhaps significant that no important Germans did so, with the brief exception of Mannheim who had little impact. The German emigration, coming from a philosophical culture [i.e. presumably Hegel] that was quite distinct from the parish-pump positivism of interbellum Vienna, avoided this island. The Frankfurt School of Marxists, Marcuse, Adorno, Benjamin, Horkheimer and Fromm went to France and then to the USA. Neumann and Reich ... (initially to Norway) followed. Lukacs went to Russia. Brecht went to Scandinavia and then to America, followed by Mann. This was a 'Red' emigration, utterly unlike that which arrived here. [Notes by RW: the question of which Jews went to the USSR is not raised. Nor is the 'New School for Social Research' in New York, now 'The New School', which as a result of the G.I. Bill, and what later came to be called 'Holocaust' propaganda, and the huge expansion in what were called universities, was able to give out fake credentials to Jews from Europe, creating thousands of 'professors', and helping to make US education damagingly weak—a tradition showing no signs of reversal. The name 'School' itself is probably borrowed from 'schule', a German or Yiddish hybrid.] 6 May 2016 It did not opt for England, because of a basic cultural and political incompatibility.19

The intellectuals who settled in Britain were thus not just a chance agglomeration. They were essentially a 'White', counterrevolutionary emigration. The individual reasons for the different trajectories to England were inevitably varied. Namier came from the powder-keg of Polish Galicia under the Habsburgs. Malinowski chose England, like his countryman Conrad, partly because of its empire. Berlin was a refugee from the Russian Revolution. Popper and Gombrich were fugitives from the civil war and Fascism of post-Habsburg Austria. Wittgenstein's motive in finally settling for England is unknown. Whatever the biographical variants, the general logic of this emigration is clear. England was not an accidental landing-stage on which these intellectuals unwittingly found themselves stranded. It was often a conscious choice - an ideal antipode of everything that they [232] rejected. Namier, who was most lucid about the world from which he had escaped, expressed his hatred of it most deeply. He saw England as a land built on instinct and custom, free from the ruinous contagion of Europe - general ideas. [Note by RW: in fact, the 'ruinous contagion' was the Jewish impact, fed by the USA's heavy industry to Jews networking around the world.] He proclaimed 'the immense superiority which existing social forms have over human movements and genius, and the poise and rest which there are in a spiritual inheritance, far superior to the thoughts, will or invention of any single generation'. 20 Rest _ the word conveys the whole underlying trauma of this emigration. The English, Namier thought, were peculiarly blessed because, as a nation 'they perceive and accept facts without anxiously enquiring into their reasons and meaning.' 21 For 'the less man clogs the free play of his mind with political doctrine and dogma, the better for his thinking.' 22 This theme is repeated by thinker after thinker; it is the hallmark of the White emigration. Namier tried to dismiss general ideas by showing their historical inefficacy; Popper by denouncing their moral iniquity ('Holism'); Eysenck by reducing them to psychological velleities; Wittgenstein by undermining their status as intelligible discourse altogether.

Established English culture naturally welcomed these unexpected allies. Every insular reflex and prejudice was powerfully flattered and enlarged in the magnifying mirror they presented to it. But the extraordinary dominance of the expatriates in these decades is not comprehensible by this alone. It was possible because they both reinforced the existing orthodoxy and exploited its weakness. For ... the unmistakable fact is that the traditional, discrete disciplines, having missed either of the great synthetic revolutions in European social thought, were dying of inanition. The English intelligentsia had lost its impetus. Already by the turn of the century, the expatriate supremacy of James and Conrad, Eliot and Pound - three Americans and a Pole - in the two great national literary forms foreshadowed later and more dramatic dispossessions. The last great products of the English intelligentsia matured before the First World War: Russell, Keynes and Lawrence. Their stature is the measure of the subsequent decline. After them, confidence and originality seeped away. There was no more momentum left in the culture; the cumulative absence of any new historical experi [233] ence in England for so long had deprived it of energy. The conquest of cultural dominance by emigres, in these conditions, becomes explicable. ... Their qualities were, in fact, enormously uneven. Wittgenstein, Namier and Klein were brilliant originators; Malinowski and Gombrich honourable, but limited pioneers; Popper and Berlin fluent ideologues; Eysenck a popular publicist. The very heterogeneity of the individuals underlines the sociological point: no matter what the quantum of talent, any foreign background was an enormous advantage in the British stasis, and might make an intellectual fortune.

[Note: the author doesn't say that the publishing industry, TV and radio, and funding of universities was dominated by Jews. The nominal respect paid by Jews to the listed mostly-Jewish 'academics' can be reliably predicted from knowledge of the then-current mass opinions of Jews. Eysenck: just one example—as per Jewish 'psychology' look at individual people, but not mass psychology, except as hating Germans. He said nothing much on groups, which of course Jews like, because it distracts from Jewish behaviour. On the other hand, Eysenck was not an anti-whit fanatic. Hence the condescending comment. - RW]

The relationship between the expatriates [Jews - RW] and the secular traditions they encountered was necessarily dialectical. British empiricism and conservatism was on the whole an instinctive, ad hoc affair. It shunned theory even in its rejection of theory. It was a style, not a method. The expatriate impact on this cultural syndrome was paradoxical. In effect, the emigrés for the first time systematized the refusal of system. They codified the slovenly empiricism of the past, and thereby hardened and narrowed it. They also, ultimately, rendered it more vulnerable. The transition from Moore to the early Wittgenstein exemplifies this movement. Wittgenstein's later philosophy reflects an awareness of the antinomy, and an attempt to retreat back to a nonsystematized empiricism, a guileless, unaggregated registration of things as they were, in their diversity. On the political plane proper, Popper's shrill advocacy of 'piecemeal social engineering' lent a somewhat mechanistic note to the consecrated processes of British parliamentarism. Apart from this aspect, however, the tremendous injection of life that emigré intelligence and élan gave a fading British culture is evident. The famous morgue and truculence of Wittgenstein, Namier or Popper, expressed their inner confidence of superiority. Established British culture rewarded them amply for their services, with the appropriate apotheosis: Sir Lewis Namier, Sir Karl Popper, Sir Isaiah Berlin and (perhaps soon) Sir Ernst Gombrich.

This was not just a passive acknowledgement of merit. It was an active social pact. Nothing is more striking than the opposite fate of the one great emigré intellectual whom Britain harboured for thirty years, who was a revolutionary. The structural importance of expatriates in bourgeois thought is confirmed by the ... ... Isaac Deutscher, the greatest Marxist historian in the world, .. A much larger figure than his compatriot Namier, .. reviled and ignored by the academic world throughout his life. He never secured the smallest university post. [He wrote a life of Stalin - RW.] ..'

- 242:

[Isaiah Berlin on freedom: Hobbes and Locke's very idea of freedom tied up with their ideas of property, it says; yet Berlin mentions the word 'property' hardly at all.]

- 243ff: Lewis Namier is regarded as a [?aristocratic] man from Poland traumatised by continental politics [the author doesn't blame, or indeed hardly mention, the First World War; cp Russell] and builds a convincing-sounding theory of the White invaders of Britain's academia.

- 258: [Note: myth?] Freud and his 'discovery of the unconscious'

- 279: [Note: Law:] '.. the aristocracy captured public schools and universities in the 16th century, preventing the development of a separate clerisy within them. Equally important was the absence of Roman Law in England, which blocked the growth of an intelligentsia based on legal faculties of the universities in the mediaeval period. On the Continent, the law schools of such centres as Bologna and Paris, which taught the abstract principles of jurisprudence, made an important contribution to the emergence of a separate intellectual group; whereas in England legal training was controlled by the guild of practising lawyers and was based on the accumulation of precedent. Weber Weber's discussion of this contrast is excellent. He writes of the concepts of English law: 'They are not "general concepts" which would be formed by abstraction from concreteness or by logical interpretation of meaning or by generalization and subsumption; nor were these concepts apt to be used in syllogistically applicable norms. In the purely empirical conduct of (English) legal practice and legal training one always moves from the particular to the particular but never tries to move from the particular to general propositions in order to be able subsequently to deduce from them the norms for new particular cases. ... No rational legal training or theory can ever arise in such a situation.' .. The ulterior consequences of this system are evident. Ben Brewster has pointed out that the Scottish Enlightenment - so unlike anything south of the border - may by contrast be traced to the tradition of Roman Law north of the border.'

280:

Some dates: Klein was born 1882 in Vienna. Malinowski 1884 in Kraków. Namier 1888 near Lvov. Wittgenstein 1889 in Vienna. Popper 1902 in Vienna. Deutscher 1907 near Kraków. Berlin 1909 in Riga. Gombrich 1909 in Vienna. Eysenck 1916 in Berlin. ...

- 280: 'Adorno spent two years in Oxford working on Husserl, unnoticed, before he went to America. A number of the greatest names in modern art spent a similar brief .. sojourn here before crossing the Atlantic to a more hospitable environment: Mondrian, Gropius, Moholy-Nagy and others. ...

Rae West notes:

The silence about Jews applies equally to the sciences: in particular nuclear science, where Hungarian Jews seem to have been exceptionally numerous on both sides of the Atlantic.

As regards 'intellectuals' in the don't-mention-Jews sense, it's perhaps worth mentioning H B Acton's 1955 book The Illusion of the Epoch: Marxism-Leninism as a Philosophical Creed. This Acton was 'Professor of Philosophy in the University of London'; his book was published by Cohen & West, a small publisher in (I'd guess) the same tradition as Lawrence & Wishart. It's curious to see Jewish influences in Acton (The Marxist Quarterly, Soviet Studies, Moscow's Foreign Languages Publishing House ...) at a time when there was intense nominal hostility to the USSR. The simple fact that there is no analysis of Jews or Judaism anywhere is proof these 'academics' were sidestepping and dodging, evading serious issues. Acton's contents list is:

PART I: DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM

I MARXIST REALISM

II MARXIST NATURALISM

PART II: SCIENTIFIC SOCIALISM

I HISTORICAL MATERIALISM

II MARXIST ETHICS

Acton's 20-page conclusion is a dialogue between Reader and Author (and includes translations attributed to Stalin—a somewhat outmoded 'thinker'). It's amusing to see the way Acton discusses 'Marxists', as though these are some species whose puzzling but presumably self-consistent views perhaps can be elucidated by a philosophy professor. The last passage is: 'Author. Let me be briefer still and say that Marxism is a farrago.' Jews are mentioned nowhere in his text. This of course is something of a parallel to 20th-century USA.

- 281: [Note: myth?] Hegel: the 'myth' of him (and e.g. Popper) apparently exposed in a book, 'The Owl and the Nightingale', by Walter Kaufmann.

LIST OF AUTHORS/TITLES AND PAGE REFERENCES:

Truths about Jews | Big-Lies Home Page

Edit, HTML, & Upload of these notes Rae West 9 May 2021. Overview at the start 29 May 2023