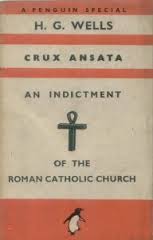

Crux Ansata

An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church

by

H.G. Wells

First published by Penguin Books, London, 1943

First US edition: Agora Publishing Co., New York, 1944

Germany ... Roman Catholic / Protestant

Italy ... Roman Catholic

Croatia ... Roman Catholic

Hungary ... Roman Catholic

Slovakia ... Roman Catholic

Bulgaria ... Orthodox Christian

Romania ... Orthodox Christian

Finland ... Protestant

Christian Leaders in Europe in the Second World War

Germany - Adolf Hitler ... Roman Catholic

Italy - Benito Mussolini ... Roman Catholic

Croatia - Ante Pavelić ... Roman Catholic

Spain - Francisco Franco ... Roman Catholic

Eire - Éamon de Valera ... Roman Catholic

Portugal ... Antonio Salazar ... Roman Catholic

Belgium - Leon Degrelle's Rex Party ... Roman Catholic

Vichy France - Henri P. Pétain - Chief of State ... Roman Catholic

Pierre Laval - Chief of Government ... Roman Catholic

Slovakia - Josef Tiso ... Roman Catholic priest

Finland - Rislo Ryti ... Protestant

Norway - Vidkun Quisling ... Protestant

Holland - Anton A. Mussert ... Protestant

Bohemia-Moravia - Emil Hacha ... Protestant

Sudetenland - Konrad Henlein ... Roman Catholic

[Table from Dennis Wise of The Greatest Story Never Told and Other Works. Note: Jews almost always use crypto-Jew figureheads, so don't assume this table is correct.]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. — Why Do We Not Bomb Rome?II. — The Development Of The Idea Of Christendom

III. — The Essential Weakness Of Christendom

IV. — Heresies Are Experiments In Man's Unsatisfied Search For Truth

V. — The City of God

VI. — The Church Salvages Learning

VII. — Charlemagne

VIII. — Black Interlude

IXa. — The Launching Of The Crusades By The Church

IXb. — Christendom Marches East

X. — A Catholic Gentleman of 1440

XI. — Social Inequality In The 14th And 15th Centuries

XII. — The Dawn Of Social Discontent

XIIIa. — The Mental Atmosphere Before The Reformation

XIIIb. — How Henry VIII Became A Protestant Prince

XIV. — The Counter-Reformation

XV. — The Jesuits

XVI. — The Continual Shrinkage Of The Roman Catholic Church

XVII. — The Struggle For Britain

XVIII. — Shinto Catholicism

XIX. — Roman Catholicism In America

XX. — The United Christian Front

XXI. — The Pretensions And Limitations Of Pope Pius XII

INTRODUCTION by 'Rerevisionist' 25 December 2014

This short book by H G Wells is infinitely saddening and depressing. Wells was about 77 when it was published, by Penguin Books in Britain. The introduction to the (ineptly-scanned; I can't guarantee the accuracy) version by Roy Glashan states that Wells had 'recently retired from the position of Minister of Allied Propaganda', though I haven't found any confirmation. He had taken part in Great War propaganda, and coined the phrase 'the war that will end war', and written Mr Britling Sees It Through—'Britling' surely must have been a small part of Britain. But by 1939 he must have seemed old-fashioned, another world away from (for example) the Hungarian Jew Sefton Delmer, the British equivalent of Ilya Ehrenburg, with his BBC-amplified Freudian manias, and the half-Jew orotund liar Churchill. Wells's outmoded attitude (at a time when the entire country was a factory for lies) is shown in some of his wartime protests against speechwriters, and writers hired to propagate official views, writing scripts to order rather than think out and present their own skillfully matured and evidenced opinions, as serious writers obviously should. Disappointingly, Wells seems to have been just another 'useful idiot', without a clear view.

It's curious how very little of the book is relevant to the Second World War, as Churchill named it. There is nothing on the rise of Japan and China, or the forces acting on them. There is nothing on the Treaty of Versailles, or why Italy and Japan both changed sides from the 'Allies'. There is little on money and finance, or on races and their impulses and instincts, or science and raw materials. The most obvious recent missing part is Jews and, for example, the Federal Reserve and Bank of England. He had this in common with other much-trumpeted intellectuals of the time: Keynes, Lawrence, Orwell, Russell, Shaw, Snow, Wells shared it—not so much a blind spot, as willful fixed turning away. Wells at least had some idea about Jewish influence.

Wells assumes the media commonplaces of New York and London: ' ... the Axis ... the abominable aggressions, murder and cruelties they have inflicted upon mankind..' and 'Pius XII, when we strip him down to reality, showed himself as unreal and ignorant as Hitler. Possibly more so. Both have been incoherent and headlong men ... a man by accident and misdirection can trail a vast trace of bloodshed and bitter suffering about the world...' In fact, Wells' printed utterances on Germany during the Great War were rather similar: Joad said it was only respect for a great man [Wells] that prevented him from reprinting some of Wells's shocking printed comments on the Germans. The Second World War was something of a re-run for him. He had learnt nothing. He had no methodology for checking and testing pre-war and wartime claims.

Wells's history of Christianity here lacks any continuo; it's essentially a series of picturesque anecdotes, most of them well-known stories, which Wells re-tells and often simply quotes, most of them, such as the 'Black Death', of dubious relevance to the main theme. They are like a series of disconnected songs. He tries to present the War as a war against Catholicism, meaning Roman Catholicism, which Wells seems to think remained rather uniform, despite spanning the lifetimes of many generations and including remarkable twists and turns. (Like almost all western Europeans, he ignores the Greek Church and Byzantium, despite its longevity; and ignores eastern Orthodox churches, notably of course the Russian Orthodox Church). This is quite common amongst people desperate to pretend Jews had and have little power: Bertrand Russell thought the 'ultimate contest' would be between the Kremlin and Vatican!

Wells' other material is based on his Outline of History of about 1920, including such ideas as that in ancient times men and women were far more easily controlled than now. (Why?) This work, the full version of which was in two volumes, was widely popular, and despite its limitations was not attacked successfully by critics, mainly because the financial and technological backbone of Wells's work could not be addressed without facing the issues of Jewish power.

I leave it to the reader to watch for Catholic historians, Chaucer, 'Shakespeare', Cromwell and Charles I, Gibbon, J R Green; and Shinto, Joseph McCabe on Roman Catholic history, and Captain Archibald Ramsay and Mosley. As Wells wrote, Churchill was commenting on Britain's bankruptcy, 'doleful news' to Britons, but not Jews. Paradoxically, Belloc, an opponent of Wells's 'Bible Christianity', proved more perceptive as regards Jews. Wells died a few years later. I take it Wells's title is a reference to the Egyptian and other origins of Christianity.

I. — WHY DO WE NOT BOMB ROME?

I cut the following paragraph from The Times of October 27th, 1942.

"The air raids on Italy have created the greatest satisfaction in Malta, which has suffered so much at Axis hands. At least the Italians now realise what being bombed means and the nature of the suffering they have so callously inflicted on little Malta since June 12th, 1940, when they showered their first bombs on what was then an almost defenceless island.

"As that bombing was intensified, especially since the Italians asked Germany's help in their vain attempt to reduce Malta, the people's reaction became violent and expressed itself in two words 'Bomb Rome', which were written prominently on walls in every locality."

On June 1st, 1942, the enemy bombed Canterbury and as near as possible got the Archbishop of Canterbury. But what is a mere Protestant Archbishop against His Holiness the Pope?

In March 1943 Rome was still unbombed.

Now consider the following facts.

We are at war with the Kingdom of Italy, which made a particularly cruel and stupid attack upon our allies Greece and France; which is the homeland of Fascism; and whose "Duce" Mussolini begged particularly for the privilege of assisting in the bombing of London.

There are also Italian troops fighting against our allies the Russians. A thorough bombing (à la Berlin) of the Italian capital seems not simply desirable, but necessary. At present a common persuasion that Rome will be let off lightly by our bombers is leading to a great congestion of the worst elements. of the Fascist order in and around Rome.

Not only is Rome the source and centre of Fascism, but it has been the seat of a Pope, who, as we shall show, has been an open ally of the Nazi-Fascist-Shinto Axis since his enthronement. He has never raised his voice against that Axis, he has never denounced the abominable aggressions, murder and cruelties they have inflicted upon mankind, and the pleas he is now making for peace and forgiveness are manifestly designed to assist the escape of these criminals, so that they may presently launch a fresh assault upon all that is decent in humanity. The Papacy is admittedly in communication with the Japanese, and maintains in the Vatican an active Japanese observation post.

No other capital has been spared the brunt of this war.

Why do we not bomb. Rome? Why do we allow these open and declared antagonists of democratic freedom to entertain their Shinto allies and organise a pseudo-Catholic destruction of democratic freedom? Why do we—after all the surprises and treacheries of this war—allow this open preparation of an internal attack upon the rehabilitation of Europe? The answer lies in the deliberate blindness of our Foreign Office and opens up a very serious indictment of the mischievous social disintegration inherent in contemporary Roman Catholic activities.

[Note [1]: New York wasn't bombed; at the time of writing the USA's Jews had got it into the war.Note [2]: Pope Pius XI (1922-39) was followed by Pope Pius XII (1939-58). Wells talks about Pius XII. Here's a Facebook comment by Steve Schleder (Dec 2104) mixing traditional Catholicism with politics:

Pius XI was in complete support of National Socialism because it was directly opposed to the Jew Bolshevikism of Russia. The Catholics were very worried about Russia and its communists errors spreading throughout the world as it was prophesied by the appearance of the Mother of Christ in Fatima, Portugal, in 1917. The Vatican hoped that National Socialism would destroy Jew Russia and gave them all of their support. It was because of this Catholic support that Russia sent 1,000 communist infiltrators into the Catholic priesthood at the end of WWII, to pay back the Church for their support of Hitler and to eventually destroy it, as it is today, a Jew Freemasonic sodomite-run Modernists "community" gathering.]

II. — THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IDEA OF CHRISTENDOM

LET us tell as compactly as possible certain salient phases in the history of the Christian organisation that led up to the breach between the various form of Protestantism and Rome. Like all human organisations that have played a part through many generations, the career of the Catholic Church has passed through great fluctuations. It had phases of vigorous belief in itself and wise leadership; it fell into evil ways and seemed no better than a dying carcass; it revived, it split. There is no need for us to explore the early development and variations of Christianity before it assumed its definite form under the patronage and very definite urgency of the Emperor Constantine. The recriminations of the early Fathers, their strange ideas and stranger practices need not concern us here. There were churches, but there was no single unified Church.

Catholicism as we know it as a definite and formulated belief came into existence with the formulation of the Nicene Creed. Eusebius gives a curious account of that strange assemblage at Nicaea, over which the Emperor, although he was not yet a baptised Christian, presided. It was not his first council of the Church, for he had already (in 314) presided over a council at Arles. He sat in the middle of the Council of Nicaea upon a golden throne, and, as he had little Greek, we must suppose he was reduced to watching the countenances and gestures of the debaters, and listening to their intonations.

The council was a stormy one. When old Arius rose to speak, one, Nicholas of Myra, struck him in the face, and afterwards many ran out, thrusting their fingers into their ears in affected horror at the old man's heresies. One is tempted to imagine the great emperor, deeply anxious for the solidarity of his empire, firmly resolved to end these divisions, bending towards his interpreters to ask them the meaning of the uproar.

The views that prevailed at Nicaea are embodied in the Nicene Creed, a strictly Trinitarian statement, and the Emperor sustained the Trinitarian position. But afterwards, when Athanasius bore too hardly upon the Arians, he had him banished from Alexandria; and when the Church at Alexandria would have excommunicated Arius, he obliged it to readmit him to communion.

A very important thing for us to note is the role played by this emperor in the unification and fixation of Christendom. Not only was the Council of Nicaea assembled by Constantine the Great, but all the great councils, the two at Constantinople (381 and 553), Ephesus (431), and Chalcedon (451), were called together by the imperial power. And it is very manifest that in much of the history of Christianity at this time the spirit of Constantine the Great is as evident as, or more evident than, the spirit of Jesus.

Constantine was a pure autocrat. Autocracy had ousted the last traces of constitutional government in the days of Aurelian and Diocletian. To the best of his lights the Emperor was trying to reconstruct the tottering empire while there was yet time, and he worked, according to those lights, without any counsellors, any public opinion, or any sense of the need of such aids and checks.

The idea of stamping out all controversy and division, stamping out all independent thought, by imposing one dogmatic creed upon all believers, is an altogether autocratic idea, it is the idea of the single-handed man who feels that to get anything done at all he must be free from opposition and criticism. The story of the Church after he had consolidated it becomes, therefore, a history of the violent struggles that were bound to follow upon his sudden and rough summons to unanimity. From him the Church acquired that disposition to be authoritative and unquestioned, to develop a centralised organisation and run parallel with the Roman Empire which still haunts its mentality.

A second great autocrat who presently emphasised the distinctly authoritarian character of Catholic Christianity was Theodosius I, Theodosius the Great (379-395). He handed all the churches to the Trinitarians, forbade the unorthodox to hold meetings, and overthrew the heathen temples throughout the empire, and in 390 he caused the great statue of Serapis at Alexandria to be destroyed. Henceforth there was to be no rivalry, no qualification to the rigid unity of the Church.

Here we need tell only in the broadest outline of the vast internal troubles the Church, its indigestions of heresy; of Arians and Paulicians, of Gnostics and Manichaeans.

The denunciation of heresy came before the creeds in the formative phase of Christianity. The Christian congregations had interests in common in those days; they had a sort of freemasonry of common interests; their general theology was Pauline, but they evidently discussed their fundamental doctrines and documents widely and sometimes acrimoniously. Christian teaching almost from the outset was a matter for vehement disputation. The very Gospels are rife with unsettled arguments; the Epistles are disputations, and the search for truth intensified divergence. The violence and intolerance of the Nicene Council witnesses to the doctrinal stresses that had already accumulated in the earlier years, and to the perplexity confronting the statesmen who wished to pin these warring theologians down to some dominating statement in the face of this theological Babel.

It is impossible for an intelligent modern student of history not to sympathise with the underlying idea of the papal court, with the idea of one universal rule of righteousness keeping the peace of the earth, and not to recognise the many elements of nobility that entered into the Lateran policy. Sooner or later mankind must come to one universal peace, unless our race is to be destroyed by the increasing power of its own destructive inventions; and that universal peace must needs take the form of a government, that is to say, a law-sustaining organisation, in the best sense of the word religious—a government ruling men through the educated co-ordination of their minds in a common conception of human history and human destiny.

The Catholic Church was the first clearly conscious attempt to provide such a government in the world. We cannot too earnestly examine its deficiencies and inadequacies, for every lesson we can draw from them is necessarily of the greatest value in forming our ideas of our own international relationships.

III. — THE ESSENTIAL WEAKNESS OF CHRISTENDOM

AND first among the things that confront the student is the intermittence of the efforts of the Church to establish the world-City of God. The policy of the Church was not whole-heartedly and continuously set upon that end. Only now and then some fine personality or some group of fine personalities dominated it in that direction. "The fatherhood of God" that Jesus of Nazareth preached was overlaid almost from the beginning by the doctrines and ceremonial traditions of an earlier age, and of an intellectually inferior type. Christianity early ceased to be purely prophetic and creative. It entangled itself with archaic traditions of human sacrifice, with Mithraic blood-cleansing, with priestcraft as ancient as human society, and with elaborate doctrines about the structure of the divinity. The gory entrail-searching forefinger of the Etruscan pontifex maximus presently overshadowed the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth; the mental complexity of the Alexandrian Greek entangled them. In the jangle of these incompatibles the Church, trying desperately to get on with its unifying task, became dogmatic and resorted to arbitrary authority.

Its priests and bishops were more and more men moulded to creeds and dogmas and set procedures; by the time they became popes they were usually oldish men, habituated to a politic struggle for immediate ends and no longer capable of worldwide views. They had forgotten about the Fatherhood of God; they wanted to see the power of the Church, which was their own power, dominating men's lives. It 'was just because many of them probably doubted secretly of the entire soundness of their vast and elaborate doctrinal fabric that they would brook no discussion of it. They were intolerant of doubts and questions, not because they were sure of their faith, but because they were not. The unsatisfied hunger of intelligent men for essential truth seemed to promise nothing but perpetual divergence.

As the solidarity and dogmatism of the Church hardened, it sloughed off and persecuted heretical bodies and individuals with increasing energy. The credulous, naive and worthy Abbot Guibert of Nogent-sous-Coucy, in his priceless autobiography, gives us the state of affairs in the eleventh century, and reveals how varied and abundant were both the internal and external revolts against the hardening authoritarianism that Hildebrand had implemented.

Abbot Guibert himself is an incipient internal rebel with criticisms of episcopal and papal corruption that already anticipate the Lollards and Luther, and the stories he tells of devils diabolical possession and infidel death-beds, witness to the wide prevalence of scoffing in Christendom even at that early time.

Yet Abbot Guibert, albeit a potential Protestant, was as completely tied to the Catholic Church as we are all tied by gravitation to the earth. There was as yet no means of breaking away. The formulae of separation had still to be discovered. Scoffers might scoff, but they came to heel on the death-bed. Four long centuries of mental travail had to intervene before these ties were broken.

But by the thirteenth century the Church had become morbidly anxious about the gnawing doubts that might presently lay the whole structure of its pretensions in ruins. It was hunting everywhere for heretics, as timid old ladies are said to look under beds and in cupboards before retiring for the night.

IV. — HERESIES ARE EXPERIMENTS IN

MAN'S UNSATISFIED SEARCH FOR TRUTH

LET us examine some of the broad problems that were producing heresies. Chief of the heretical stems was the Manichaean way of thinking about the conflicts of life.

The Persian teacher Mani was crucified and flayed in the year 277. His way of representing the struggle between good and evil was as a struggle between a power of light and a power of darkness inherent in the universe. All these profound mysteries are necessarily represented by symbols and poetic expressions, and the ideas of Mani still find a response in many intellectual temperaments to-day. One may hear Manichaean doctrines from many Christian pulpits. But the orthodox Catholic symbol was a different one.

Manichaean ideas spread very widely in Europe, and particularly in Bulgaria and the south of France. In the south of France the people who held them were called the Cathars. They arose in Eastern Europe in the ninth century among the Bulgarians and spread westward. The Bulgarians had recently become Christian and were affected by dualistic eastern thought. They insisted upon an excessive sexlessness. They would eat no food that was sex-begotten—eggs, cheese even, were taboo but they ate fish because they shared the common belief of the time that fish spawned sexlessly. Their ideas jarred so little with the essentials of Christianity, that they believed themselves to be devout Christians. As a body they lived lives of ostentatious purity in a violent, undisciplined and vicious age. They were protected by Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand), because their views enforced his imposition of celibacy upon the clergy (of which we shall tell in Chapter VII) in the eleventh century. But later their experiments in the search for truth carried them into open conflict with the consolidating Church. They resorted to the Bible against the priests. They questioned the doctrinal soundness of Rome and the orthodox interpretation of the Bible. They thought Jesus was a rebel against the cruelty of the God of the Old Testament, and not His harmonious Son, and ultimately they suffered for these divergent experiments.

Closely associated with the Cathars in the history of heresy are the Waldenses, the followers of a man called Waldo, who seems to have been comparatively orthodox in his theology, and less insistent on the "pure" life, but offensive to the solidarity of the Church because he denounced the riches and luxury of the higher clergy. Waldo was a rich man who sold all his possessions in order to preach and teach in poverty. He attracted devoted followers and for a time he was tolerated by the Church. But his followers and particularly those in Lombardy, went further. Waldo had translated the New Testament, including the Revelation, into Provençal, and presently his disciples were denouncing the Roman Church as the Scarlet Woman of the Apocalypse. This was enough for the Lateran, and presently we have the spectacle of Innocent III, after attempts at argument and persuasion, losing, his temper and preaching a Crusade against these troublesome enquirers. The story of that crusade is a chapter in history that the Roman Catholic historians have done their best to obliterate.

Every wandering scoundrel at loose ends was enrolled to carry fire and sword and rape and every conceivable outrage among the most peaceful subjects of the King of France. The accounts of the cruelties and abominations of this crusade are far more terrible to read than any account of Christian martyrdoms by the pagans, and they have the added horror of being indisputably true.

Yet they did not extirpate the Waldenses. In remote valleys of Savoy a remnant survived and lived on, generation after generation, until it was incorporated with the general movement of the Reformation and faced and suffered before the reinvigorated Roman Catholic Church in the full drive of the Counter Reformation. Of that we shall tell later.

The intolerance of the narrowing and concentrating Church was not confined to religious matters. The shrewd, pompous, irascible, disillusioned and rather malignant old men who manifestly constituted the prevailing majority in the councils of the Church, resented any knowledge but their own knowledge, and distrusted any thought that they did not correct and control. Any mental activity but their own struck them as being at least insolent if not positively wicked. Later on they were to have a great struggle upon the question of the earth's position in space, and whether it moved round the sun or not. This was really not the business of the Church at all. She might very well have left to reason the things that are reason's, but she seems to have been impelled by an inner necessity to estrange the intellectual conscience in men.

Had this intolerance sprung from a real intensity of conviction it would have been bad enough, but it was accompanied by an undisguised contempt for the mental dignity of the common man that makes it far less acceptable to our modern ideas. Quite apart from the troubles in Rome itself there was already manifest in the twelfth century a strong feeling that all was not well with the spiritual atmosphere. There began movements—movements that nowadays we should call "revivalist"—within the Church, that implied rather than uttered a criticism of the sufficiency of her existing methods and organisation. Men sought fresh forms of righteous living outside the monasteries and priesthood.

One outstanding figure is that of St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226). This pleasant young gentleman had a sudden conversion in the midst of a life of pleasure, and, taking a vow of extreme poverty, gave himself up to an imitation of the life of Christ, and to the service of the sick and wretched, and more particularly to the service of the lepers who then abounded in Italy.

He was joined by numbers of disciples, and so the first Friars of the Franciscan Order came into existence. An order of women devotees was set up beside the original confraternity, and in addition great numbers of men and women were brought into less formal association. He preached, unmolested by the Moslems be it noted, in Egypt and Palestine, though the Fifth Crusade was then in progress. His relations with the Church are still a matter for discussion. His work had been sanctioned by Pope Innocent III, but while he was in the East there was a reconstitution of his order, intensifying discipline and substituting authority for responsive impulse, and as a consequence of these changes he resigned its headship. To the end he clung passionately to the ideal of poverty, but he was hardly dead before the order was holding property through trustees and building a great church and monastery to his memory at Assisi. The disciplines of the order that were applied after his death to his immediate associates are scarcely to be distinguished from a persecution; several of the more conspicuous zealots for simplicity were scourged, others were imprisoned, one was killed while attempting to escape, and Brother Bernard, the "first disciple", passed a year in the woods and hills, hunted like a wild beast.

This struggle within the Franciscan Orr is interesting, because it foreshadowed the great troubles that were coming to Christendom. All through the thirteenth century a section of the Franciscans were straining at the rule of the Church, and in 1318 four of them were burnt alive at Marseilles as incorrigible heretics. There seems to have been little difference between the teaching and the spirit of St. Francis and that of Waldo in the twelfth century, the founder of the massacred but unconquerable sect of Waldenses. Both were passionately, enthusiastic for the spirit of Jesus of Nazareth. But while Waldo rebelled against the Church, St. Francis did his best to be a good child of the Church, and his comment on the spirit of official Christianity was only implicit. But both were instances of an outbreak of conscience against authority and the ordinary procedure of the Church. And it is plain that in the second instance, as in the first, the Church scented rebellion.

A very different character to St. Francis was the Spaniard St. Dominic (1170-1221), who was, above all things, orthodox. For him the Church was not orthodox enough. He was a reformer on the Right Wing. He had a passion for the argumentative conversion of heretics, and he was commissioned by Pope Innocent III to go and preach to the Albigenses. His work went on side by side with the fighting and massacres of the crusade. Whom Dominic could not convert, Innocent's Crusaders slew. Yet his very activities and the recognition and encouragement of his order by the Pope witness to the rising tide of discussion and to the persuasion even of the Papacy that force was a remedy.

In several respects the development of the Black Friars or Dominicans—the Franciscans were the Grey Friars—shows the Roman Church at the parting of the ways, committing itself more and more deeply to a hopeless conflict with the quickening intelligence and courage of mankind. She whose duty it was to teach, chose to compel. The last discourse of St. Dominic to the heretics he had sought to convert is preserved to us. It betrays the fatal exasperation of a man who has lost his faith in the power of truth because his truth has not prevailed.

"For many years," he said, "I have exhorted you in vain, with gentleness, preaching, praying and weeping. But according to the proverb of my country, 'Where blessing can accomplish nothing, blows may avail', we shall rouse against you princes and prelates, who, alas'! will arm nations and kingdoms against this land,... and thus blows will avail where blessings and gentleness have been powerless."[1]

[1] Encyclopaedia Britannica, art. "Dominic".

V. — THE CITY OF GOD

So the intolerance of the Catholic Church drove steadily towards its own disruption. Nevertheless for nearly a thousand years the idea of Christendom sustained a conception of human unity more intimate and far wider than was ever achieved before.

As early as the fifth century Christianity had already become greater, sturdier and more enduring than any empire had ever been, because it was something not merely imposed upon men, but interwoven with their deeper instinct for righteousness. It reached out far beyond the utmost limits of the empire, into Armenia, Persia, Abyssinia, Ireland, Germany, India and Turkestan. It had become something no statesman could ignore.

This widespread freemasonry, which was particularly strong in the towns and seaports of the collapsing Empire, must have had a very strong appeal to every political organiser. The Christians were essentially townsmen and traders. The countrymen were still pagans (pagani = villagers).

"Though made up of widely scattered congregations," says the Encyclopaedia Britannica in its article on "Church History", "it was thought of as one body of Christ, one people of God. This ideal unity found expression in many ways. Intercommunication between the various Christian communities was very active. Christians upon a journey were always sure of a warm welcome from their fellow disciples. Messengers and letters were sent freely from one Church to another. Missionaries and evangelists went continually from place to place. Documents of various kinds, including gospels and apostolic epistles, circulated widely. Thus in various ways the feeling of unity found expression,, and the development of widely separated parts of Christendom conformed more or less closely to a common type."

Ideas of worldly rule by this spreading and ramifying Church were indeed already prevalent in the fourth century. Christianity was becoming political. Saint Augustine, a native of Hippo in North Africa, who wrote between 354 and 430, gave expression to the political idea of the' Church in his book, The City of God. The City of God leads the mind very directly towards the possibility of making the world into a theological and organised Kingdom of Heaven.. The city, as Augustine puts it, is "a spiritual society of the predestined faithful, but the step from that to a political application was not a very wide one. The Church was to be the ruler of the world over all nations, the divinely-led ruling power over a great league of terrestrial states.

Subsequently these ideas developed into a definite political theory and policy. As the barbarian races settled and became Christian, the Pope began to claim an overlordship of their Kings. In a few centuries the Pope had become in Latin Catholic theory, and to a certain extent in practice, the high priest, censor, judge and divine monarch of Christendom; his influence, as we have noted, extended far beyond the utmost range of the old empire. For more than a thousand years this idea of the unity of Christendom, of Christendom as a sort of vast Amphictyony, whose members even in wartime were restrained from many extremities by the idea of a common brotherhood and a common loyalty to the Church, dominated Europe. The history of Europe from the fifth century onward to the fifteenth is very largely the history of the failure of this great idea of a divinely ordained and righteous world government to realise itself in practice.

VI. — THE CHURCH SALVAGES LEARNING

IF the dark disorders of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, the newly organised Catholic Church played an important role in the preservation of learning and social ideas. St. Benedict and Cassiodorus in particular set themselves to the salvage of books and teaching, and among their immediate followers was one of the first great Popes, Gregory the Great. In those days the local Christian priest was often too ignorant,to understand the Latin phrases he mumbled and muttered at his services. Gregory's educational energy corrected that. He restored the priests' Latin. So that later the Catholic Church retained its widespread solidarity in spite of the most extraordinary happenings in Rome. It would no doubt have preferred to keep its Latin language without the Latin classics, but their use was unavoidable if the language was to be steadied and sustained.

St. Benedict was born at Spoleto in Italy, a young man of good family. The shadow of the times fell upon him, he conceived a disgust for the evil in life, and, like Buddha a thousand years before him, he took to the religious life and set no limit to his austerities. Fifty miles from Rome is Subiaco, and there at the end of a gorge of the Arno, beneath a jungle growth of weeds and bushes, rose a deserted palace built by the Emperor Nero, overlooking an artificial lake that had been made in those days of departed prosperity by damming back the waters of the river. Here with a hair shirt as his chief possession, Benedict took up his quarters in a cave in the high southward-looking cliff that overhangs the stream, in so inaccessible a position that his food had to be lowered to him on a cord by a faithful admirer. Three years he lived here, and his fame spread as Buddha's did, as a great saint and teacher.

Presently we find him no longer engaged in self-torment, but controlling a group of twelve monasteries, the resort of a great number of people. Youths are brought to him to be educated, and the whole character of his life has ceased to be ascetic.

From Subiaco he removed to Monte Cassino, half-way between Rome and Naples, a lonely and beautiful mountain in the midst of a great circle of majestic heights. Here, it is interesting to note that in the sixth century A.D. he found a temple of Apollo and a sacred grove, and the countryside still worshipping at this shrine. His first labours had to be missionary labours, and with difficulty he persuaded the simple pagans to demolish their temple and cut down their grove. The establishment upon Monte Cassino became a famous and powerful centre within the lifetime of its founder. Mixed up with the imbecile inventions of marvel-loving monks about demons exorcised, disciples walking on the water, and dead children restored to life, we can still detect something of the real spirit of Benedict. Particularly significant are the stories that represent him as discouraging extreme mortification. He sent a damping message to a solitary who had invented a new degree in saintliness by chaining himself to a rock in a narrow cave. "Break thy chain," said Benedict, "for he true servant of God is chained not to rocks by iron, but to righteousness by Christ."

Next to the discouragement of solitary self-torture, Benedict insisted upon hard work. Through the legends shine the clear indications of the trouble made by his patrician students and disciples who found themselves obliged to toil instead of leading lives of leisurely austerity under the ministrations of the lower class brethren.

A third remarkable thing about Benedict was his political influence. He set himself to reconcile Goths and Italians, and it is clear that Totila, his Gothic king, came to him for counsel and was greatly influenced by him. When Totila retook Naples from the Greeks, the Goths protected the women from insult and treated even the captured soldiers with humanity. Belisarius, Justinian's general, had taken the same place ten years previously, and had celebrated his triumph by a general massacre.

Now the monastic organisation of Benedict was a very great beginning in the Western world. One of his prominent followers was Pope Gregory the Great (540-604), the first monk to become Pope (590); he was one of the most capable and energetic of the Popes, sending successful missions to the unconverted, and particularly to the Anglo-Saxons. He rules in Rome like an independent king, organising armies, making treaties. To his influence is due the imposition of the Benedictine rule upon nearly the whole of Latin monasticism.

Gregory the Great ruled in Rome like an independent king organising armies, making treaties. It was he who saw two fair captives from Britain, and, having asked whence they came and being told they were Angles, said they might be angels—non Angli sed Angeli—rather than Angles if they had the Faith. He made it his special business to send missionaries to England. This is a high water mark in the chequered history of the Roman Church. From Gregory I it passes into a phase of decadence not only at Rome but throughout its entire sphere of influence.

VII. — CHARLEMAGNE

AN interesting amateur in theology who was destined to drive a wedge into the solidarity of the Christian system was the Emperor Charlemagne, Charles the Great, the friend and ally of King Alfred of Wessex. The wedge was unpremeditated. The learned, investing history with the undeserved dignity their scholarly minds craved, have endowed Charles with an almost inhuman foresight. He was the son of Pepin, who had been Mayor of the Palace to the last of the Merovingian Kings, and, on the strength of his being de facto King, he appealed to the Pope to transfer the Crown to his head. This the Pope did. Everywhere in Europe the ascendant rulers seized upon Christianity as a unifying force to cement their conquests. Christianity became a banner for aggressive chiefs—as it did in Uganda in Africa in the bloody days before that country was annexed to the British Empire.

Charlemagne was most simply and enthusiastically Christian, and his disposition to sins of the flesh, to a certain domestic laxity—he is accused among other things of incestuous relations with his daughters—merely sharpened his redeeming zeal for the Church. An aggressive Church had long since decided that sins of the flesh are venal sins when weighed against unorthodoxy, and he was able to offer up vast hecatombs of conquered pagans to appease the more and more complaisant Catholic Church. He insisted on their becoming Christians, and to refuse baptism or to retract after baptism were equally crimes punishable by death. After he was crowned Emperor he obliged every male subject over the age of twelve to renew his oath of allegiance and undertake to be not simply a good subject but a good Christian.

A new Pope, Leo III, in 795, made Charlemagne Emperor. Hitherto the court at Byzantium had possessed a certain Indefinite authority over the Pope. Strong emperors like Justinian had bullied the Popes and obliged them to visit Constantinople; weak emperors had annoyed them ineffectively. The idea of a breach, both secular and religious, with Constantinople had long been entertained at the Lateran, and in the Frankish power there seemed to be just the support that was necessary if Constantinople was to be defied.

So upon his accession Leo III sent the keys of the tomb of St. Peter and a banner to Charlemagne as the symbols of his sovereignty in Rome as King of Italy. Very soon the Pope had to appeal to the protection he had chosen. He was unpopular in Rome; he was attacked and ill-treated in the streets during a procession, and obliged to fly to Germany (799). Eginhard says his eyes were gouged out and his tongue cut off. He seems, however, to have had both eyes and tongue again a year later. Charlemagne brought him back to Rome and reinstated him (800).

Then occurred a very important scene. On Christmas Day in the year 800, as Charles was rising from prayer in the Church of St. Peter, the Pope, who had everything in readiness, clapped a crown upon his head and hailed him Caesar and Augustus. There was great popular applause. But Eginhard, the friend and biographer of Charlemagne, says that the new Emperor was by no means pleased by this coup of Pope Leo's. If he had known this was to happen, he said, "he would have not entered the Church, great festival though it was."

No doubt he had been thinking and talking of making himself Emperor, but he had evidently not intended that the Pope should make him Emperor. He had had some idea of marrying the Empress Irene, who at that time reigned in Constantinople, and so becoming monarch of both Eastern and Western Empires. But now he was obliged to accept the title in the manner that Leo had adopted, as a gift from the Pope, and in a way that estranged Constantinople and secured the separation of Rome from the Byzantine Church.

At first Byzantium was unwilling to recognise the imperial title of Charlemagne. But in 811 a great disaster fell upon the Byzantine Empire. The pagan Bulgarians, under their prince Krum, defeated and destroyed the armies of the Emperor Nicephorus, whose skull became a drinking cup for Krum. The great part of the Balkan peninsula was conquered by these people. After this misfortune Byzantium was in no position to dispute this revival of the empire in the West, and in 812 Charlemagne was formally recognised by Byzantine envoys as Emperor and Augustus.

The defunct Western Empire rose again as the "Holy Roman Empire". While its military strength lay north of the Alps, its centre of authority was Rome. It was from the beginning a divided thing, a claim and an argument rather than a necessary reality. The good German sword was always clattering over the Alps into Italy, and missions and legates toiling over in the reverse direction. But the Germans never could hold Italy permanently, because they could not stand the malaria that the ruined, neglected, undrained country fostered. And in Rome, as well as in several other of the cities of Italy, there smouldered a more ancient tradition, the tradition of the aristocratic republic, hostile to both Emperor and Pope.

In spite of the fact that we have a life of him written by his contemporary, Eginhard, the character and personality of Charlemagne are difficult to visualise. Eginhard was a poor writer; he gives many particulars, but not the particulars that make a living figure. Charlemagne, he says, was a tall man, with a rather feeble voice; and he had bright eyes and a long nose. "The top of his head was round," whatever that may mean, and his hair was "white". Possibly that means he was a blond. He had a thick, rather short neck, and "his belly too prominent". He wore a tunic with a silver border, and gartered hose. He had a blue cloak, and was always girt with his sword, hilt and belt being of gold and silver.

He was a man of great animation and his abundant love affairs did not interfere at all with his incessant military and political labours. He took much exercise was fond of pomp and religious ceremonies, and gave generously. He was a man of considerable intellectual enterprise, with a self-confident vanity rather after the fashion of William II, the ex-German Emperor, who died at Doorn so unimpressively the other day.

His mental activities are interesting, and they serve as a sample of the intellectuality of the time. Probably he could read; at meals he "listened to music or reading, but he never acquired the art of writing;" he used, says Eginhard, "to keep his writing book and tablets under his pillow, that when he had leisure he might practise his hand in forming letters, but he made little progress in an art begun too late in life." He certainly displayed a hunger for knowledge, and he took pains to attract men of learning to his Court.

These learned men were, of course, clergymen, there being no other learned men then in the world and naturally they gave a strongly clerical tinge to the information they imparted. At his Court, which was usually at Aix-la-Chapelle or Mayence, he whiled away the winter season by a curious institution called his "school", in which he and his erudite associates affected to lay aside all thoughts of worldly position, assumed names taken from the classical writers or from Holy Writ, and discoursed upon learning and theology. Charlemagne himself was "David". He developed a considerable knowledge of theology, and it is to him that we must ascribe the proposal to add the words filioque to the Nicene Creed—an addition that finally split the Latin and Greek Churches asunder. But it is more than doubtful whether he had any such separation in mind. He wanted to add a word or so to the Creed, just as the Emperor William II wanted to leave his mark on the German language and German books, and he took up this filioque idea, which was originally a Spanish innovation. Pope Leo discreetly opposed it. When it was accepted centuries later, it was probably accepted with the deliberate intention of enforcing the widening breach between Latin and Byzantine Christendom.

The filioque point is a subtle one, and a word or so of explanation may not seem amiss to those who are uninstructed theologically. Latin Christendom believes now that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father and the Son; Greek and Eastern Christians, that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, without any mention of the Son. The latter attitude seems to incline a little towards the Arian point of view. The Catholic belief is that the Father and the Son have always existed together, world without end; the Greek orthodox idea is tainted by a very human disposition to think fathers ought to be at least a little senior to their sons. The reader must go to his own religious teachers for precise instruction upon this point.

The disposition of men in positions of supreme educational authority in a community, to direct thought into some particular channel by which their existence may be made the more memorable, is not uncommon: The Emperor William, for instance, helped to make the Germans a people apart, and did much for the spectacle-makers of Germany, by using his influence to sustain the heavy Teutonic black letter and insisting upon the rejection of alien words and roots from the good old German vocabulary. "Telephone" for instance was anathema, and "Fernsprecher" was substituted; and wireless became "drahtlos". So nationalism in Germany achieved the same end as the resistance of English stupidity to orthographic changes, and made the language difficult for and repulsive to foreigners.

The normal speech of Charlemagne was Frankish. He may have understood Latin, more particularly if it was used with consideration, but he could have had no opportunity of Greek. He made a collection of old German songs and tales, but these were destroyed by his son and successor, Louis the Pious, because of their paganism.

VIII. — BLACK INTERLUDE

FOR a very long time the hold of the Emperors and the Popes upon the City of Rome was a very insecure one. Many of the surviving patrician families and also the Roman mob claimed the most conflicting privileges in the election and removal of the Popes, the German Emperor claimed similar rights, and on the other hand the popes would assert their rights to depose and excommunicate emperors. In this confusion popes multiplied, even a layman, John XIX, was made pope, and there were overlapping popes inconsiderable abundance. In 1045 there were three popes struggling in Rome, the notoriously vicious Benedict IX, Sylvester III and Gregory VI. Gregory VI bought the Papacy from Benedict, who subsequently went back on his bargain.

Hildebrand became Pope Gregory VII. He succeeded Pope Alexander, who, under his inspiration, had been attempting to reform and consolidate the Church organisation. He imposed celibacy on the clergy and so cut them off from family and social ties. It consolidated the Church but it dehumanised the Church. Hildebrand fought a long fight with the Emperor Henry IV. Henry deposed him and Gregory deposed and excommunicated the Emperor, who repented and did penance at Canossa. Afterwards Henry regretted his humiliation and created an Anti-Pope, Clement III. He besieged Gregory who held out in the Castle of St. Angelo. Robert Guiscard, a Norman freebooter, whom Pope Nicholas had made "Duke of Apulia and Calabria and future Lord of Sicily by the Grace of God and St. Peter", came to the rescue, drove out the Emperor and Anti-Pope and incidentally sacked Rome. After which Gregory went off under the protection of the Normans and died at Salerno, a hated and unhappy man, a good and great-spirited man defeated by the uncontrollable complexities of life.

So the story of schisms and conflicts runs on through the records of the Church. Many of the popes fought for power for the vilest ends, but we do such men as Gregory VII and Urban II (the Pope of the First Crusade) the grossest injustice if we ignore the fact that behind this barbaric struggle for power there could be long views and disinterested aims. Conformity to the concepts of Christendom or a merely brutal life impulse were the alternative guides between which men had to choose in the atmosphere of that period. Men "sinned" violently and defiantly and yet were superstitiously afraid. Death-beds generally reeked with penitence, abject confessions and pious bequests. It is difficult for a modern mind to imagine how much in that age of confusion men could believe, and how little dignity, coherence and criticism there was in their beliefs.

How far things could go with the weak, the vicious and the insolent is shown by one phase in the history of Rome at this time, an almost indescribable phase. The decay of the Empire of Charlemagne had left the Pope unsupported, he was threatened by Byzantium and by the Saracens (who had taken Sicily), and face to face with the unruly nobles of Rome. Among the most powerful of these nobles were two women. Theodora and Marozia, mother and daughter,[1] who in succession held that same Castle of St. Angelo, which Theophylact, the patrician husband of Theodora, had seized together with most of the temporal power of the Pope. These two women were as bold, unscrupulous and dissolute as any male prince of the time could have been, and they are abused by masculine historians as though they were ten times worse. Marozia seized and imprisoned Pope John X (928), who speedily died under her hands. Her mother, Theodora, had been his mistress. Marozia subsequently made her illegitimate son Pope, under the title of John XI.

[1] Gibbon mentions a second Theodora, the sister of Marozia.

After him her grandson, John XII, filled the chair of St. Peter. Gibbon's account of the manners and morals of John XII is suffused with blushes and takes refuge at last beneath a veil of Latin footnotes. This Pope, John XII, was finally degraded by the German Emperor Otto, scion of a new dynasty that had ousted the Carlovingians, who came over the Alps and down into Italy to be crowned in 962. Harsh critics of the Church call this phase in its history the pornocracy.

That "pornocracy" sounds much more awful for the Catholic Church than was the reality. It has very little controversial weight if our criticism is to be just. It was a purely Roman scandal, and the Faithful throughout Christendom probably never heard a word about this "pornocratic" phase. They went about their simple religious duties as they had been taught. It was not an age of easy travel, and practically nobody in the tenth century went to Rome or heard what was happening there. That sort of stress was to come later.

IXa — THE LAUNCHING OF THE CRUSADES BY THE CHURCH

IN this brief history of the complex effort of the human mind and will to secure some mastery over its internal and external perplexities, the Crusades, and particularly the First Crusade, demand our particular attention. The First Crusade displays "Christendom" at its maximum effectiveness as a consolidating and justifying idea, and it shows also how the essential instability of the Roman leadership and the ideological freakishness of Charlemagne combined with the inherent self-seeking and confusion in the human mind at large; to defeat every ostensible purpose of this great eastward drive. Every ostensible purpose. But the reaction of the mingling of ideas and purposes hat ensued had unforeseen consequences in the disintegration of Christendom that was presently to ensue.

The Crusades were the direct work of the Church. It had been consolidating itself slowly from the uncertainties of the earlier Dark Ages. The establishment of clerical celibacy in the ninth and tenth centuries was isolating it from the social mass, and the retreat from the passionate side of life to monasticism dotted the western world with centres of industrious husbandry, which availed themselves of the protection of the developing feudal organisation and provided retreats from which men of considerably riper years emerged as ministers, councillors, educators. Becket was about fifty when he was killed, Anselm lived to be seventy-five, Lanfranc's age is uncertain, but it was somewhere about eighty. No wonder they carried weight in a generally puerile world.

A man is as old as his arteries, we say nowadays, but the key to a real and authoritative old age for these divines of the Dark Ages was probably the inherited soundness of their teeth. Those whose teeth decayed ceased to speak with dignity and authority. There was no dentistry except extraction..

"Benefit of clergy", which worked out at last as a convenient mitigation of harsh penal laws, arose out of the claim of the consolidating Church to take clerics out of the hands of the temporal power and deal with them in its own fashion. But the monasteries were only aggressive when they dared; they were not immune from local disorders and had to be steered with discretion. There was incessant bickering, robbery and warfare, and intermittent local famine, and the standard of life rose and fell here and there and from time to time.

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the civilisation of Western Europe probably displayed far less social insecurity and inequality, and far less gross brutality, than in the succeeding period. There were regions and phases of comparative health and vitality. But such phases meant the accumulation of lootable resources, and opened the way to conceptions of conquest upon a larger and more lucrative scale. The Norman Conquest of England was a considerable achievement for that age. The tradition of the Roman Empire, the tradition of great and rich cities to the south-east, still haunted men's imaginations and did much to prepare them for the greater adventure of the Crusades.

The older and wiser heads who were consolidating a renascent Latin Church in the tenth and eleventh centuries were struggling against the incessant bickering warfare of the times. The Church then was something very different from Pope Pacelli's Church of to-day. In its reawakened eleventh-century form, under the direction of that greatest of papal statesmen, Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand), it was the most civilised and civilising thing in the Western world. It was at its best. Not only the Roman Church as we know it, but all the Protestant sects, are derived from it. It had tried various expedients to put a truce upon local violence, and it seized upon the Turkish ill-treatment of pilgrims to the Holy Sepulchre as an incentive. These Turks had smashed the Byzantine armies and driven them out of Asia Minor. They sat down in Nicaea, opposite Byzantium itself. In this extremity Alexis Comnenus, the Byzantine Emperor, appealed to Pope Gregory VII for help, and the Latin-speaking West responded promptly and vigorously. Both the Western Empire and the Church saw plainly before it the subjugation of the Eastern world by the West.

IXb — CHRISTENDOM MARCHES EAST

THE incitement to crusade aroused a stupendous and varied response. It released all the latent unifying forces that had accumulated about the idea of Christendom.

In the beginning of the seventh century we saw Western Europe as a chaos of social and political fragments, with no common idea nor hope, a system shattered almost to a dust of self-seeking individuals. Now, at the close of the eleventh century, we discover a common belief, a linking idea, to which men may devote themselves, and by which they can co-operate together in a universal enterprise. We realise that, in spite of much weakness and intellectual and moral unsoundness, to this extent the Christian Church had worked. We are able to measure the evil phases of tenth-century Rome, the scandals, the filthiness, the murders and violence, at their proper value by the scale of this fact. No doubt, not only in Rome itself, but all over Christendom, there had been many lazy, evil and foolish ecclesiastics, but it is manifest that in spite of them a task of teaching and co-ordination had been accomplished by a great multitude of right-living priests and monks and nuns. A new and greater amphictyony, the amphictyony of Christianity, had come into the world, and it had been built by thousands of these anonymous faithful lives.

And the response to the appeal of Urban II was not confined only to what we should call educated people. It was not simply knights and princes who were willing to go crusading. Side by side with the figure of Urban we must put that of Peter the Hermit, a type novel to Europe, albeit a little reminiscent of the Hebrew prophets. This man appeared preaching the crusade to the common people. He told a story—whether truthful or untruthful hardly matters in this connection—of his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, of the wanton destruction at the Holy Sepulchre by the Seljuk Turks, who took it somewhen about 1075—the chronology of this period is still very vague—and of the exactions, brutalities and deliberate cruelties now practised upon the Christian pilgroms to the Holy Places. Barefooted, clad in a coarse garment, riding on an ass and bearing a huge cross, this man travelled about France and Germany, and everywhere harangued vast crowds in church or street or market-place.

Here for the first time we discover the masses of Europe with a common idea. Here is a collective response of indignation to the story of a remote wrong, a swift realisation of a common cause by rich and poor alike. You cannot imagine that happening in the Empire of Augustus Caesar, or, indeed, in any previous state in the world's history. Something of the kind might perhaps have been possible in the far smaller world of Hellas, or in Arabia before Islam. But this movement affected nations, kingdoms, tongues and peoples. We are dealing with something new that has come into the world.

From the first this flaming enthusiasm was mixed with baser elements. There was the cold and calculated scheme of the free and ambitious Latin Church to subdue and replace the Byzantine Church; there was the freebooting instinct of the Normans, now tearing Italy to pieces, which turned readily enough to a new and richer world of plunder; and there was something in the multitude who now turned their faces east, something deeper than love in the human composition, namely, fear-born hate, that the impassioned appeals of the propagandists and the exaggeration of the horrors and cruelties of the infidel had fanned into flame.

And still other forces were at work; the intolerant Seljuks and the intolerant Fatimites lay now an impassable barrier across the eastward trade of Genoa and Venice that had hitherto flowed through Baghdad, Aleppo and Egypt. Unless Constantinople and the Black Sea route were to monopolise Eastern trade altogether, they must force open these closed channels. Moreover, in 1094 and 1095 there had been a pestilence and famine from the Scheldt to Bohemia, and there was great social disorganisation.

"No wonder," wrote Mr. Ernest Barker, "that a stream of emigration set towards the East, such as would in modern times flow towards a newly discovered goldfield—a stream carrying in its turbid waters much refuse: tramps and bankrupts, camp-followers and hucksters, fugitive monks and escaped villeins, and marked by the same motley grouping, the same fever of life, the same alternations of affluence and beggary, which mark the rush for a goldfield to-day."

But these were secondary contributory causes. The fact of predominant interest to the historian of mankind is this will to crusade suddenly revealed as a new mass possibility in human affairs.

The first forces to move eastward were great crowds of undisciplined people rather than armies, and they sought to make their way by the valley of the Danube, and thence southward to Constantinople. This has been called the "people's crusade". Never before in the whole history of the world had there been such a spectacle as these masses of practically leaderless people moved by an idea. It was a very crude idea. When they got among foreigners, they did not realise they were not already among the infidel. Two great mobs, the advance guard of the expedition, committed such excesses in Hungary, where the language was incomprehensible to them, that they were massacred. A third host began with a great pogrom of the Jews in the Rhineland, and this multitude was also destroyed in Hungary. Two other swarms under Peter himself reached Constantinople, to the astonishment and dismay of the Emperor Alexius. They looted and committed outrages, until he shipped them across the Bosphorus, to be massacred rather than defeated by the Seljuks (1096).

This first unhappy appearance of the "people" as people in modern European history was followed in 1097 by the organised forces of the First Crusade. They came by diverse routes from France, Normandy, Flanders, England, Southern Italy and Sicily and the will and power of them were the Normans. They crossed the Bosphorus and captured Nicaea, which Alexius snatched away from them before they could loot it.

Then they went to Antioch, which they took after nearly a year's siege. Then they defeated a great relieving army from Mosul.

A large part of the crusaders remained in Antioch, a smaller force under Godfrey of Bouillon went on to Jerusalem. To quote Barker again: "After a little more than a month's siege, the city was finally captured (July 15th, 1099). The slaughter was terrible; the blood of the conquered ran down the streets, until men splashed in blood as they rode. At nightfall, 'sobbing for excess of joy', the crusaders came to the Sepulchre from their treading of the winepress, and put their blood-stained hands together in prayer. So, on that day of triumph, the First Crusade came to an end."

The authority of the Patriarch of Jerusalem was at once seized upon by the Latin clergy with the expedition, and the Orthodox Christians found themselves in rather a worse case under Latin rule than under the Turk. There were already Latin principalities established at Antioch and Edessa, and between these various courts and kings began a struggle for ascendancy. There was an unsuccessful attempt to make Jerusalem a property of the Pope. These are complications beyond our present scope.

Let us quote, however, a characteristic passage from Gibbon, to show the drift of events:

"In a style less grave than that of history, I should perhaps compare the Emperor Alexius to the jackal, who is said to follow the steps and devour the leavings of the lion. Whatever had been his fears and toils in the passage of the First Crusade, they were amply recompensed by the subsequent benefits which he derived from the exploits of the Franks. His dexterity and vigilance secured their first conquest of Nicaea, and from this threatening station the Turks were compelled to evacuate the neighbourhood of Constantinople.

"While the Crusaders, with blind valour, advanced into the midland countries of Asia, the crafty Greek improved the favourable occasion when the emirs of the sea coast were recalled to the standard of the Sultan. The Turks were driven from the islands of Rhodes and Chios; the cities of Ephesus and Smyrna, of Sardes, Philadelphia and Laodicea, were restored to the empire, which Alexius enlarged from the Hellespont to the banks of the Maeander and the rocky shores of Pamphylia. The churches resumed their splendour; the towns were rebuilt and fortified; and the desert country was peopled with colonies of Christians, who were gently removed from the more distant and dangerous frontier.

"In these paternal cares we may forgive Alexius if he forgot the deliverance of the holy sepulchre; but by the Latins he was stigmatised with the foul reproach of treason and desertion. They had sworn obedience and fidelity to his throne; but he had promised to assist their enterprise in person, or, at least, with his troops and treasures; his base retreat dissolved all their old gains; and the sword, which had been the instrument of their victory, was the pledge and title of their just independence. It does not appear that the emperor attempted to revive his obsolete claims over the kingdom of Jerusalem, but the borders of Cilicia and Syria were more recent in his possession and more accessible to his arms. The great army of the crusaders was annihilated or dispersed; the principality of Antioch was left without a head, by the surprise and captivity of Bohemond; his ransom had oppressed him with a heavy debt; and his Norman followers were insufficient to repel the hostilities of the Greeks and Turks.

"In this distress, Bohemond embraced a magnanimous resolution, of leaving the defence of Antioch to his kinsman, the faithful Tancred; of arming the West against the Byzantine Empire, and of executing the design which he inherited from the lessons and example of his father Guiscard. His embarkation was clandestine; and if we may credit a tale of the Princess Anna, he passed the hostile sea closely secreted in a coffin. (Anna Comnena adds that, to complete the imitation, he was shut up with a dead cock; and condescends to wonder how the barbarian could endure the confinement and putrefaction. This absurd tale is unknown to the Latins.)..."

So Gibbon, caustic but veracious, detesting Roman and Byzantine with an impartial detestation, bears his witness.

It was in this widening conflict of the Latin and the Greek that that theological freak of Charlemagne, the filioque clause, became important politically.

We have traced the growth of this idea of a religious government of Christendom—and through Christendom of mankind—and we have shown how naturally and how necessarily, because of the tradition of world empire, it found a centre at Rome. The Pope of Rome was the only Western patriarch; he was the religious head of a vast region in which the ruling tongue was Latin; the other patriarchs of the Orthodox Church spoke Greek and so were inaudible throughout his domains;, and the two words filioque, which had been added to the Latin creed, now split off the Byzantine Christians by one of those impalpable and elusive doctrinal points upon which there is no reconciliation. (The final rupture was in 1054.)

The broad reality of the Crusades was that all the surplus energy of the West, in a passion of greed, piety and virtuous indignation, poured down upon the far more sophisticated Levant and returned with a thousand hitherto unheard-of things. Most of the rank and file were killed off ("The men were splendid"), but the knights and noblemen who returned with their retinues came back with silk and velvet, dyes and chain armour, and cravings and conceptions of luxury that had been submerged in the minds of western men since the collapse of the Roman Empire.

X. — A CATHOLIC GENTLEMAN OF 1440

[Note: a revisionist view of Gilles de Rais is that he was a victim of a campaign of vilification in which there was no truth - RW]

LET us now sketch the face and quality of human life in Europe at that time, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. We must clear our minds of the popular persuasion that the people who went to and fro in the towns and villages we inherit were very much like the people who walk about our streets to-day, except that they wore different costumes. That is a complete delusion. There was no such fancy dress ball. These fifteenth-century people were, on the average, twenty years younger, they were less healthy looking, and they stank quite abominably. The barbarism of the period was not primitive. It had arisen out of the decadence of a preceding social order. The great public baths of the Roman tradition had faded out of the crumbling social edifice. Not only are we misled by the natural anthropomorphism, so to speak, that makes us image the crowds in the past essentially like the crowds of to-day, but we are also misled by the pictures and records which misrepresent the spectacle of the times.

The printed book had still to dawn upon the world, and whatever record was made of the show of things was kept by monkish chroniclers employed by the Princes and Potentates of the time. These keepers of the records sat and toiled to make their manuscripts as bright and pleasing to their employers as possible. So that our vision of that time is magically illuminated by their art. A reeking slum of human indignity is lit up by the flattering brightness of the subservient chronicler and the blazons of heraldry, and it is only when we subject them to a closer scrutiny that we are able to grasp the squalid facts of human life during that period.

Then as now the world had its own loveliness, sunrise and sunset, the glorious onset of spring, the golden autumn, the white frost flowers upon the branches, but the dyes and fabrics of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century clothing in Christendom had none of the gilt and shining pigmentation of the illuminator. Clothing must have been still crude in colour and stale and dirty in substance. The normal span of life was brief and men were flimsier. We find the armour of our ancestors too small and tight for even puny men to-day. But then, one may ask, was it worn by real grown-up men? These people were often married at thirteen, they were warriors and leaders in their later teens; they became cruel old satyrs at six-and-thirty. In fact they never grew up either physically or mentally. They lived in a world of witless lordship and puerile melodrama.

From this disillusioning digression upon the brilliance in the fifteenth century, we can turn to one exceptionally "brilliant" young man, Gilles de Rais, a type of his time, of whose life we have by various accidents an exceptionally full record. He was married to a rich heiress at sixteen after two earlier attempts to make a match for him (the earliest at thirteen) had fallen through. He was a boy not only of exceptional energy but of exceptional gifts. He patronised music. He illuminated and bound books. And from the outset he was what people call "unbalanced".

Some people may be disposed to account for his peculiar aberrations by saying he just "went mad". But madness is as pitiless and consistent a process as anything else that can happen, the sequence of ideas in those we call insane is as inevitable, you can find their origins and their associations, and nowadays when we are all out of harmony with our conditions of survival, to say merely that he "went mad" does not even put him outside the pale of normal experience. Exceptionally wealthy at the outset, his mental liveliness made him a spendthrift. Like many youngsters born rich, he could not imagine being hard up until he was. He liked to give extravagant entertainments, mysteries and moralities. From first to last he was a good Catholic, conscientiously and unfeignedly religious. But for that he might never have been hung. He dabbled in alchemy and the black arts; there was no Monte Carlo for him in those days and no turf—and he tried to make up for his magic by extravagant charity and special masses.

All this is the behaviour of an uncontrolled upper-form schoolboy with a belief in his luck, an uncritical piety of the "Onward Christian Soldiers" type, and an unanalysed disposition to torment fags. It must be cited to place him definitely in relation to our own minds, but not in any way as a condonation of what he did. He was cruel; by all our standards he was hideously cruel; he delighted in the tormenting of children; and the points best worth discussing about him here are, first, whether he was an exceptional sinner, or whether his crimes were the outcome of a mental disposition that has always been operative since that wretched congestion of mankind which is called civilisation began; and secondly, and more important for our present purpose, how far the religious beliefs and practices of Catholic Christendom in the fifteenth century really condemned his abominations.

The Christians before the days of Constantine the Great had stood out valiantly against the cruelties of the arena and for the practical brotherhood of man, but was the Church still doing so when Gilles de Rais was a great nobleman? The records tell that he was hung for the torture and murder of 140 children to which he confessed, in the year 1440. He had committed sacrilege and infringed clerical immunity by entering the Church of St. Etienne de Mer Morte just after Mass and dragging out a certain Jean de Ferron who was kneeling there in prayer. This precipitated the hostility and suspicion that was accumulating against him. As a sequel to this outrage he was arrested and cited before the Bishop of Nantes on various charges, of which sacrilege and heresy were the chief and these murders a secondary issue, A parallel enquiry was made by Pierre de l'Hôpital, President of the Breton parlement, by whose sentence he was finally condemned. His piety and abject confession saved him from torture, of which he probably went in profound dread because of the fascination it had for him.

He was hung, "housell'd, appointed, anel'd", more fortunate than Hamlet's father, and his body was saved from being burnt by "four or five dames and demoiselles of great estate", who removed his body from the flames of the pyre built so that he would fall into it. Manifestly they thought no great evil of what he had done. His two associates had no such social standing, and their bodies were burnt. This, I understand, will cause them considerable trouble at the Resurrection from which the aristocratic Gilles will be exempt.

He began life brilliantly and honourably. He must have seemed a splendid young man to the world about him, and by every current standard he was splendid. He was a close ally and supporter of Joan of Arc, with whom he fought side by side at Orleans and later at Jargeau and Patay. He carried out the coronation of Charles VII at Reims, and he was made marichal of France upon that important occasion.

This riddle of condonation of social inequality and cruelty confronts us at every stage of the long "Martyrdom of Man". Man is evidently an animal which will fight, and on occasion fight desperately, but which prefers to fight at an advantage. He has been readier to use moderation and make concessions when fighting against his quasi-equals than against those who are altogether helpless, and always he has shown little or no regard for his inferiors, the rank and file, still less for the feeble folk who get in his militant way. When a scorched earth policy had to be undertaken, or if they were Jews or infidels, they counted for nothing at all.

The Merchant of Venice, the dullest play perhaps produced by the Shakespeare group, exhibits an internal struggle between a liberal-minded and a prejudiced element in the group of players which vamped up that fundamentally dreary story of hate against hate. The struggle between these two elements goes on in every human grouping, not only between one man and another, but between what we are apt to call a man's better self and his lower nature between his sense of righteousness and his even more deeply rooted prejudices. It runs through the entire Christian story, and our case against the Catholic Church is that, albeit it originated in a passionate assertion of the conception. of brotherly equality, it relapsed steadily from the broad nobility of its beginnings and passed over at last almost completely to the side of persecution and the pleasures of cruelty.

XI. — SOCIAL INEQUALITY IN THE 14TH AND 15TH CENTURIES